By Serena Balani and Neha Sati

Amadou Diallo’s name became synonymous with “41 shots”.

He was killed in 1999 by four NYPD officers, who fired at him 41 times inside the doorway of his Bronx apartment building. The incident etched his name into public memory through explosive news coverage.

But beyond the headlines, who was Amadou Diallo?

In “Boli”, we dive into Amadou’s life – from his dreams to his time in New York. We hear from neighbors and friends who go down memory lane to tell us his side of the story.

Join us as we go beyond “41 shots” to learn more about Amadou Diallo.

TRANSCRIPT

SATI: Excuse me. Hi. Hello. Hi. I’m doing a podcast on Amadou Diallo. I’m going around the neighborhood to ask people what they remember about him. Do you know who he was? Yeah. Can you tell me what you know about him?

LAZETTE SAMUEL: All I know is he got shot by some cops. They thought he had a gun in his wallet or something like that.

FATI ADAM: Oh that Guinea boy who was killed here? I wasn’t here but I know the story.

JOSE RAUL: The guy who the police shot? Uh-huh, yeah.

JOSE LOUIS CARDONA: Yeah, I remember the “bam bam bam bam bam”.

MUSIC IN

SATI: That’s what most people remember about Amadou Diallo. The gunshots.

BALANI: Amadou was a young immigrant from West Africa. He was also an unarmed Black man who was killed by four white police officers 25 years ago. They fired 41 shots while he stood in the doorway of his apartment building. 19 hit him. The first likely killed him.

SATI: The four police officers who killed him were charged with second-degree murder, but were acquitted. The verdict caused a huge uproar at the time.

MUSIC OUT

BALANI: Today, there’s a giant mural of Amadou’s face taking up a wall on the corner of Wheeler Avenue at Westchester in the Bronx. The place near where he was killed.

SATI: His death has been covered extensively by the media. But so little was said about his life.

Who was Amadou Diallo? Why did he leave his home and family to come to the U.S.? What was his life like in the months and weeks leading up to his death?

THEME MUSIC IN

BALANI: To answer those questions we watched hours of news archives, documentaries, and court testimony. We read dozens of newspaper stories and looked to Amadou’s mother, Kadiatou Diallo’s memoir: My Heart Will Cross This Ocean, for early details of his life.

SATI: We also tracked down some of his old friends from New York and even some old neighbors.

BALANI: This is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today.

SATI: This season we’re going back to 1999 to tell the story of Amadou Diallo. An unarmed Black man who was killed by four white police officers.

SATI: I’m Neha Sati

BALANI: And I’m Serena Balani

SATI: This is Shoe Leather Season Five – “After Amadou”

BALANI: And you’re listening to “Boli”

THE SOLUTION IS U.S.A.

SATI: Amadou Diallo was born in 1975 in Guinea, a country in West Africa.

His mother Kadiatou Diallo, was 16 years old. And Amadou was her first child.

MUSIC IN

SATI: Growing up, Amadou’s family moved often, mostly for his father’s work. Saikou Diallo had many businesses, including Gem Trading.

As a child, Amadou lived in Liberia, Thailand, and Singapore.

He loved to read, play basketball and soccer.

ARCHIVAL URBANX TV FOOTAGE

KADIATOU: He was ahead of his time.

BALANI: That’s Amadou’s mother – Kadiatou in an interview with UrbanX TV

KADIATOU: He loved computers, he loved music, he loved hip-hop music. And he was… That was his life.

BALANI: He even loved American pop music. He sometimes had Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” on repeat at home.

Amadou’s mother had three more children and eventually divorced Amadou’s father, and started a business of her own.

By the time Amadou was ready to go to college, he spoke five languages. Including Spanish and Thai.

MUSIC OUT

BALANI: But he had a stutter, sometimes finding it difficult to express himself.

SATI: In 1996, the year Amadou turned 21, he made a bold move.

More than 200 Guineans immigrated to the U.S. that year – some of them for political reasons. It was one of the largest groups to immigrate from Guinea in a decade.

And true to his nature, Amadou would be traveling among them.

BALANI: But not because he was protesting a government, but because he wanted to pave his own path. Earn a college degree in Computer Science literacy.

ARCHIVAL BRONXNET FOOTAGE

KADIATOU: He graduated from the French International High School in Bangkok. And then right after that he went to Singapore, and he was interested in computer science literacy. So his dream was to come to the US, work hard and pay his way to college, and achieve his education.

BALANI: Amadou believed in the American Dream, the idea that education was the key to success

Before heading to New York City, Amadou left a note for his mother.

SATI: “The solution is U.S.A.”, he wrote. “Don’t leave my brothers and sister here.”

AMADOU’S ROUTINE

BALANI: Amadou already had a cousin, living in the U.S. when he arrived. That’s how he met his first roommate, Momodou Kujabi. And how he ended up at 1157 Wheeler Avenue in the Bronx.

KUJABI: So that’s how we ended up living, the three of us, Me, Salou, who is Amadou’s cousin, and Amadou Diallo himself.

SATI: He wanted to work for himself. Amadou had an interest in business. It came from his father, and according to his roommate, Momodou Kujabi, from his Fulani Heritage.

So, Amadou set up a cart selling socks, gloves, hats, and musictapes on East 14th Street. He often worked six or seven days a week, for 10 or 12 hours a day.

And when he came home from work, he liked to watch TV.

MUSIC IN

KUJABI: He liked baseball. Especially the Yankees. There’s no game of the New York Yankees that he wouldn’t watch when he had the time to.

BALANI: And Momodou says, he was learning to cook.

KUJABI: You know, like you come here, but you prefer to have your own dish because that’s what you know. His cousin would try to help him. Back home usually the male don’t cook. All the females cook. But when we move, there’s nobody there, there’s no sister or mother to cook for you. You have to do it, you have to learn.

BALANI: Momodou remembers Amadou as quiet – perhaps because he grew up with a stutter. He said he was kind.

KUJABI: He don’t talk much, you know, somebody you can easily interact with.

SATI: Two years after arriving in the US, Amadou was 23 years old. And still living in that two-bedroom apartment on Wheeler Avenue with Momodou.

From being the new guy on the block, Amadou was slowly becoming a friendly face in the neighborhood. He was waving hello to his neighbors, occasionally helping them out with small tasks. Like his neighbor Taylor.

TAYLOR: My daughter was in. I think it was…

SATI: Amadou would watch her car while she dropped her young daughter inside to do her homework. He would do this so she didn’t get a ticket.

TAYLOR: He was a great person.

MUSIC OUT

BALANI: He was also getting ready to apply to college. He’d already saved $9,000.

On the morning of February 3rd, 1999, Momodou left for work at six am.

Momodou returned home that day just before midnight. He checked for mail, and then went up to his apartment.

Here’s Momodou testifying in court about that day.

ARCHIVAL COURT TV FOOTAGE

KUJABI: When I went inside my apartment, I went, took off my uniform, went to the bathroom. Then I came out. When I came out, I was going to get some water out of the fridge. Then I saw Amadou Diallo lying on the couch

BALANI: Amadou was watching TV, with his head resting on the arm of the sofa.

The two men spoke briefly about the electric bill. Amadou was the one who usually paid. Momodou said he would leave the money on the table the next morning.

KUJABI: After that, I left him there watching TV. Then I went in my room. Then I went to sleep.

SATI: It would be the last time Momodou would see Amadou alive.

BALANI: Sometime after midnight, Momodou heard some noise and then banging at the door.

It was two police detectives.

KUJABI: One of the officers asked me to go and see, you know, if I can identify the person.

BALANI: Momodou went downstairs to the vestibule. He saw Amadou lying on the ground. Surrounded by blood.

BOLI

MUSIC IN

SATI: In the mid-1990’s, Anthony Lovari was a struggling musician.

BALANI: He was just about to move into his new apartment with a friend.

But that friend backed out, making Lovari responsible for coming up with rent on his own.

SATI: One night, he’s sitting on the stoop of his apartment, when he bums a cigarette from two women who were walking by.

LOVARI: So just out of despair I looked in and I said, I’m so sorry. Does anybody have an extra cigarette? And one of them said, sure. And they gave it to me. And they were like, why do you look so sad? So then I just started crying and telling them everything that was going on. And, one of them was like, don’t worry, boo, I got you. My name is Bridget and you know, my boyfriend, he lives up around the corner. And don’t worry, we got you. We got you. so we started hanging out.

LOVARI: This is what, back in the day. This is like how it was. This is like the late 90s, you know, things like that. It might sound strange. Now to anybody listening now, what would you go off with strangers and, you know, but this is just how it was in that in that particular area.

BALANI: One of the women introduces him to her boyfriend, Raz. He owns a convenience store on East 14th Street. The three of them start hanging out.

LOVARI: One day there was a gentleman in front of his store and he had bootleg cassettes and – do we need to explain what cassettes are – to the young people? What? Do we? Okay, so –God, I feel old. Cassettes… Cassettes were like CDs, but they were small. They were cassettes, tape players, Walkmans… like guys, the 80s throwbacks. Just look up cassettes. You put them in Walkmans. Anyways.

Then Raza said, “Oh, this is my friend, “Boli”.

MUSIC OUT

SATI: Lovari says Boli had a great smile. And he was cute.

LOVARI: [laughs] And of course, I flirted, because that’s just how I am. I remember one of the first things I said was like “you have a really nice smile”. And he was just very polite. He didn’t flirt back… dammit. And he just gave a gracious smile back and said, oh, thank you, very gentle, very, very gentle, very meek, very gentle. That’s important to remember.

BALANI: A comfort grew between the two. Lovari began asking Boli for cassette tapes of his favorite artists – Mary J Blige, Dru Hill, Faith Evans, and Little Kim.

SATI: One of Lovari’s jobs was at a record store.

LOVARI: Coconuts, at the time, and they would have… the paper would be delivered.

BALANI: One morning, Lovari was opening up the store.

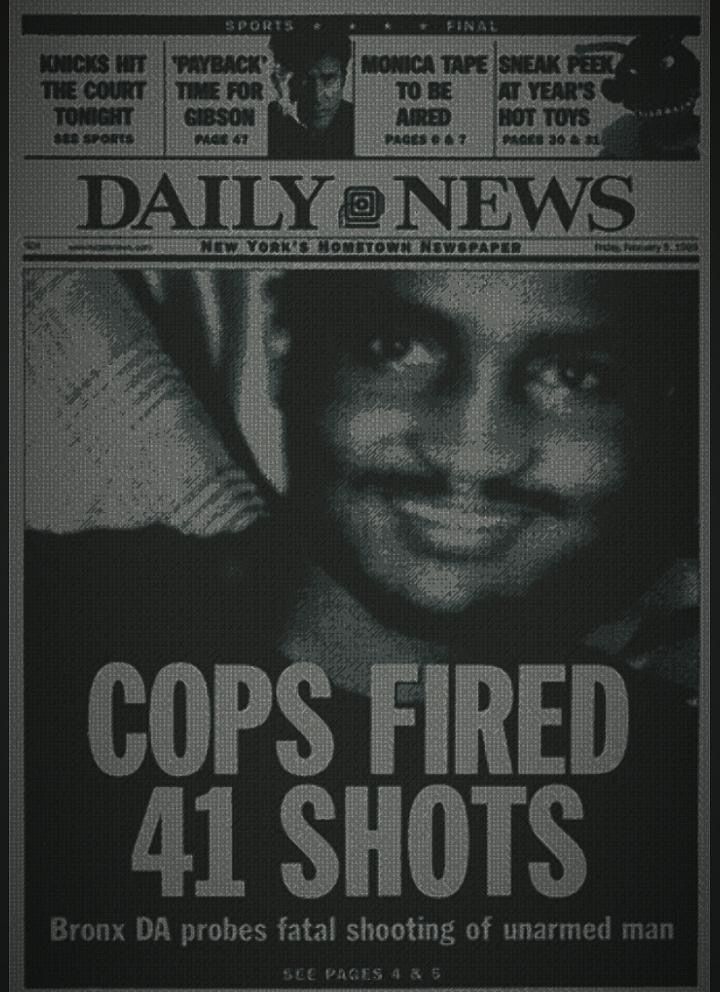

LOVARI: And there was the newspaper on the floor, and it was Daily News, and it said 41 shots.

And there was a very a black and white dark photo, almost like blurry photo.

MUSIC IN

LOVARI: And I picked it up and I said, that is fucked up. That’s horrible.

SATI: On the front page was a story about a man who’d been shot 41 times by four police officers. The man had been standing in the entryway of his own apartment building.

LOVARI: And I put the papers inside and I continued to help open up the store with my manager.

BALANI: A little while later, Lovari gets a beep on his pager from Raz.

SATI: He usually pages when Boli stocks the cassettes that Lovari’s been waiting for. So Lovari ignores it and keeps working.

LOVARI: We all did this. We didn’t have cellphones but we managed to hang out. Like if you were dating somebody or if it was your friend, you could write, 1-4-3, which meant I love you, which was one letter, which was “I”, the number one. 4 was four letters for love, L-o-v-e. And then 3 for “you”, y-o-u. 1-4-3. So that was the other things you put, 1-4-3.

If you were mad at somebody, you could write asshole and you turn it around. It was 3-7-0-4-5-5-8. And you turn it round, looked like “asshole”.

SATI: But then Raz pages again. And it wasn’t some silly pager code.

LOVARI: I said, hey, Raza, know what’s going on? I think he beeped me twice. And he was like, oh, that’s terrible. It’s horrible. Did you see 41 times he was shot? I said, oh yeah, I said, I saw, I saw.

I was like, I saw that, that on the front page. I was like, that’s horrible what they did to that guy. And he was like.. the guy? I was like, yeah. I was like, that’s messed up. I saw the front page of that. And he was like, that was Boli.

I said what? I said, no, no, no, that, that, that’s not the name.

LOVARI: The photo was so dark. Actually, I thought it was like quite, quite an unprofessional photo for a newspaper to have. That’s how dark the picture was.

I looked again and then of course, the smile. Then I looked at the eyes and I was like, oh, it was him. But it said Amadou, that was why I didn’t equate it at first. Because it said Amadou Diallo.

SATI: Lovari’s “Boli” was New York City’s “Amadou”

KADIATOU GOES TO HER SON

MUSIC IN

BALANI: Meanwhile, thousands of miles away in Guinea, Amadou’s Grandmother is having bad dreams. She dreams of a calf. The calf wants milk, but its mother doesn’t have any to give.

SATI: The next morning, a phone rings.

Amadou’s aunt, Kadiatou’s sister, picks up.

It’s a relative from New York, and he’s asking to speak to a man in the house. Something is wrong. Isn’t it nighttime in New York? What could they want to say at this hour? And isn’t Amadou asleep?

BALANI: The voice on the other end of the line doesn’t want to speak to Kadiatou. Because in her family tradition, bad news is usually passed to the male family members.

SATI: But Kadiatou doesn’t take no for an answer.

MUSIC OUT

BALANI: Five days after Amadou’s death, his mother Kadiatou lands in New York.

BALANI: She needs to make sense of what happened to her son.

SATI: She steps off the plane at Kennedy International Airport, and into the City’s arena. Two big players – Mayor Rudy Giuliani

ARCHIVAL C-SPAN FOOTAGE

GIULIANI: We can’t allow the understandable emotions that emerge from a horrible incident to cloud reality.

SATI: And activist Al Sharpton – both want her on their team.

REV SHARPTON: Racial Profiling was one of the issues that had to be dealt with.

SATI: the first thing that Kadiatou wants to do is go to 1157 Wheeler Avenue in the Bronx. Where her son lived and died.

BALANI: So a black NYPD van takes her there.

SATI: She gets out of the police van – there is a crowd of people surrounding her – she walks up to the front stoop of the building, nearly collapsing on the way…. and then cries out her son’s name…

ARCHIVAL CBS FOOTAGE

KADIATOU: Amadou! Amadou! Amadou! Amadou!

SATI: Kadiatou is taken up to Amadou’s apartment. She sees his room. She never realized it was so small. She smells his clothes. She meets people who say they knew him.

BALANI: She’s then whisked away by the New York City Police Department into a hotel room. They tell her that the City will pay for her stay.

SATI: Here’s Al Sharpton speaking on the documentary “Trial by Media”.

ARCHIVAL TRIAL BY MEDIA FOOTAGE

REV SHARPTON: I said She’s with the cops and Giuliani. They got her a big suite overlooking Central Park on 5th Avenue. They’re going to use her against us.

BALANI: In this room, she meets someone from Sharpton’s team. That’s when she realizes she doesn’t feel comfortable staying under the City’s care.

BALANI: Sharpton arranges for a different hotel room, and tells Kadiatou that the community will pay for it. It’s a move that places her, knowingly or unknowingly, on Sharpton’s team.

THE TRIAL

ARCHIVAL DEMOCRACY NOW! TAPE

SHARPTON: Amadou!

CROWD: Amadou!

SHARPTON: Amadou!

CROWD: Amadou!

SHARPTON: Amadou!

CROWD: Amadou!

SHARPTON: Amadou!

CROWD: Amadou!

BALANI: In the days and weeks following Amadou’s death, Al Sharpton helps organize protestors. They demand the officers who shot Amadou be held accountable.

These protests get a lot of attention.

MUSIC IN

BALANI: At a news conference Kadiatou, Amadou’s mother, speaks out about her son’s death for the first time.

ARCHIVAL TRIAL BY MEDIA FOOTAGE

REV. SHARPTON: The mother of our brother, Ahmed Diallo…

BALANI: Here’s Kadiatou in “Trial by Media”, talking about that News Conference.

KADIATOU: The first night at the National Action Network, that was the first night I spoke out in public. In my life.

SATI: One month after the killing, the 4 officers are indicted for second-degree murder. The trial begins.

Inside the courtroom, Kadiatou watches as the officers who shot her son talk about him to a jury. This is from Sean Carrol’s testimony – one of the four cops on trial for shooting Amadou.

ARCHIVAL COURT TV FOOTAGE

LAWYER: Were you suspicious of him?

CARROL: Oh, absolutely.

LAWYER: What made you suspicious? Could you tell us, please?

CARROL: Just his actions alone. The way he was peering up and down the block and the way he he… It would appear to me that he slinked back into the to the vestibule.

SATI: There was an objection over the word “slinked”.

CARROL: He went back into the vestibule. And then, as we were backing up his head, peering out and keeping a vigilant eye on us, looking. And I’m looking backwards and I can see him. He’s looking at us.

BALANI: To the cops, Amadou looked suspicious.

SATI: But other people who knew Amadou, describe him differently.

MUSIC OUT

LOVARI: I’ve said this. If I’m walking down the street at 3 o’clock in the morning and I see a person. And there’s nobody else around. I’m crossing the street. It’s 3 o’clock in the morning, is dark. I’m the only person. There’s another person. I’m crossing the street. I don’t want no trouble. But I would say if I was walking down the street. And I didn’t know Amadou. But I saw Amadou not knowing who he was. I wouldn’t cross the street. I would walk right by him because he was a meek person. He was. He had a gentle persona.

BALANI: Momodou, Amadou’s old roommate, thinks about what that moment must have been like for Amadou.

KUJABI: This guy is very quiet. You know people that they want to say something. It takes time for them to say a single word. How do you call it?

When you’re with him, you have to give him that time for him to say what he has to say. You cannot rush on him. That’s how he is.

KUJABI: He-e-e-e. O-O-Oh-Okay. That’s how he talks.

SATI: Oh. Did he still have a stutter?

KUJABI: That’s what I was trying to tell you. He stutters a lot.

SATI: Oh.

KUJABI: He stutters a lot. That’s just what I was trying to get – What word do I use here?

BALANI AND SATI: Ohhhh

KUJABI: Even the simplest explanation is going to take him a while.

SATI: Amadou stuttered – he needed time to say what he had to say. Momodou still thinks about how this might have affected his interaction with the cops that night.

KUJABI: I think they were over-doing what they were supposed to do. And they didn’t take the time to get to know – You know because otherwise this wouldn’t have happened. Because Amadou is a very quiet, calm guy. So I’m thinking probably they actually did something… And he couldn’t say, and didn’t know and everything started getting out of hand in that split second. I think that’s what happened.

MUSIC IN

BALANI: One year after Amadou’s death, the jury reaches a verdict.

ARCHIVAL COURT TV FOOTAGE

JURY: Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty…

BALANI: All 4 officers acquitted.

SATI: Kadiatou, had become a powerful spokesperson for her son. She did not want his humanity to be lost in the media frenzy.

SATI: But she was not able to testify.

SATI: She later told reporters that even after the trial, she still didn’t understand what happened to her son.

THE CIVIL LAWSUIT

BALANI: The protests continued after the verdict.

ARCHIVAL AP FOOTAGE

REV SHARPTON: We gonna boycott in this city.

We will hold our wallet until the federal government brings charges of civil rights on the case of Amadou Diallo.

SATI: Kadiatou filed a civil suit against the city of New York.

SATI: Three years later, she won the case and was awarded a 3 Million dollar settlement.

ARCHIVAL DEMOCRACY NOW! TAPE

KADIATOU: I do not want to dwell so much in what is the amount, what is supposed to be done about financial situation for my son. Because nothing, nothing can replace him.

BALANI: Kadiatou started The Amadou Diallo Foundation with the settlement money from the city. The foundation has since awarded over 50 scholarships since her son’s death.

25 YEARS LATER

[AMBI]

BALANI: It’s a cold February evening when I walked up to Amadou Diallo Place. There’s a crowd of people surrounding a giant mural of Amadou’s face.

KADIATOU: Thank you so much for being here today. This is, to mark one very historic moment.

BALANI: Kadiatou Diallo is speaking at a Vigil. It’s the 25th anniversary of Amadou’s death.

KADIATOU: He had dreams. And he was about to achieve his dreams. His dreams was cut short. By 41 bullets.

MUSIC IN

SATI: In death, Amadou Diallo had become a cause to rally behind. An example of policing gone wrong.

But Amadou was also a traveler. Someone who believed in education and bought into the American dream. He was a man who was learning to cook African dishes. Who liked to listen to Bruce Springstein and watch the Yankees.

A son to his mother.

And he was becoming a friendly face on Wheeler Avenue.

MUSIC OUT

[AMBI]

THEME MUSIC IN

BALANI: Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written, and produced by Neha Sati and Serena Balani

Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Rachel Quester and Peter Leonard are our co-professors. Special thanks to Columbia Digital Libraries.

SATI: Shoe Leather’s theme music – ‘Squeegees’ – is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller, remixed by Peter Leonard.

Other Music by Blue dot sessions. Our Season five graphic was created by Indy Scholtens with help from Serena Balani.

THEME MUSIC OUT