By Ryan Kilkenny and Jiayu Liang

Andy Velez was a co-founder of ACT UP, a legendary activist group known for its willingness to take practically any nonviolent action to fight AIDS. At the same time ACT UP was making itself known, New York City’s lower east side was changing fast. Neighborhoods that once belonged to artists and punks were lost to developers and yuppies.

In this episode, Ryan Kilkenny and Jiayu Liang look at the culture of protest Andy helped create, and how Andy’s son Ben would pick these values up and bring them to a different cause in the summer of 1988.

This episode uses material from Andy Velez’s ACT UP Oral History. You can access all 187 member interviews at actuporalhistory.org.

TRANSCRIPT

JIAYU: Content warning: There’s use of homophobic slurs and mention of suicidal feelings in this episode.

MUSIC STARTS

RYAN: My friends and I love Rent. The musical – not paying our landlords.

TAPE ( RENT – SEASONS OF LOVE): “Five hundred, twenty five thousand, six hundred minutes…”

RYAN: Rent was a groundbreaking show when it opened in 1996. It depicts a group of struggling artists living in the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the AIDS epidemic.

MUSIC OUT

And it was inspired by the reality of life in New York in the 1980s and 90s.

It tells the story of the toll that AIDS has taken on queer communities.

SOUND: Knocking on Billy’s door, door opening

BILLY: Hello.

RYAN: Hi.

BILLY: Ryan?

RYAN: Yeah. Hi.

BILLY: Nice to meet you, I’m Billy.

RYAN: Nice to meet you

BILLY: Come on in.

SOUNDS OF SIRENS

RYAN: Even before I walked in I could see Billy Aronson’s five Daytime Emmys through the front window.

RYAN: It’s my first time seeing Emmys in real life. It’s very exciting.

BILLY: My wife put them there. I mean I didn’t fight her.

MUSIC STARTS

RYAN: Billy is a playwright. The original idea for Rent came from him – a modern-day adaptation of the opera La Bohème.

Billy never lived in the Lower East Side. But the AIDS crisis hit every corner of New York.

BILLY: I was really aware of AIDS, everybody was in the mid eighties. Um, it was horrifying. When you found out about it, you found out someone was dying. And usually that meant a lot of people that you knew were dying.

RYAN: Eventually, he’d team up with a composer named Jonathan Larson.

BILLY: But right away he had this feeling of explicit, emotional, big. And he said it would bring the MTV generation back to the theater.

RYAN: Rent did end up changing musical theater. But Jonathan never lived to see it. He died the night before Rent’s off-broadway debut.

And the cultural impact of Rent is not lost on Billy.

BILLY: At the time, the worst of AIDS in the United States had passed because there were ways to live with it then. But we were still looking at the basic problem that people were thought to be less or that we were picking on the weak. We were speaking out about that. Um so that’s great. I think it also brought a lot of people to the theater. Jonathon was exactly right.

MUSIC OUT

RYAN: But that’s not all that Rent did. It has introduced AIDS activism – including the group ACT UP – to audiences for decades. Including me and my friends.

MUSIC (RENT – LA VIE BOHEME: As it broadcasts the words): “Actual Reality – ACT UP – Fight AIDS!” Check…

JIAYU: ACT UP was willing to do anything – take any risk – to bring attention to the AIDS crisis.

Its members and their loved ones were dying from AIDS. They had nothing to lose. So they were willing to move fast and take risks.

MUSIC STARTS (SHOE LEATHER THEME MUSIC)

ANDY: One of the most powerful tools that ACT UP had was, we had no shame. There was nothing we couldn’t do, as long as it was non-violent.

JIAYU: That’s Andy Velez. He was a co-founder ACT UP, and would help define a culture of protest in the 1980’s. A culture of protest that his son would later pick up and bring to a different cause.

I’m Jiayu Liang.

RYAN: And I’m Ryan Kilkenny.

And this is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York’s past to understand how yesterday’s news affects us today.

JIAYU: When you think of the 80s, protest might not immediately come to mind. But New York City was changing fast. Neighborhoods that once belonged to artists and punks were lost to developers and so-called yuppies. The kind of people who worked on Wall Street. And people were taking a stand.

RYAN: This is Shoe Leather season four – It’s Our Fucking Park.

You’re listening to ACT UP, Fight Back.

MUSIC OUT

JIAYU: The 80s were a defining moment in the queer community. It was the first time anyone had ever heard of AIDS.

ARCHIVE: Federal health officials say as many as one million Americans may have been infected with the AIDS virus and more than 12,000 are expected to develop the deadly disease next year. And that would double the cases since 1981 nationwide.

RYAN: For Andy Velez’s son Ben, all those things would intersect on a hot summer night in August, 1988, in a park on the Lower East Side.

BEN: That whole week, you know, we were all hanging out and like, kind of like, what are we going to do? Like the war has come to us.

INTRODUCING ANDY AND THE AIDS CRISIS

JIAYU: Ben Velez is in the fifth grade when he discovers punk rock.

BEN: I had the Dead Kennedys’ In God We Trust. It’s the one that the song Nazi Punks Fuck Off is on, and, you know, the cover is Jesus being hung on a dollar bill like a collage of dollar bills. And it says in God We Trust.

JIAYU: The back of the record prints the full lyrics to the songs. Because like all good punk records, Ben says, you can’t understand what they’re saying. But it’s important stuff.

Then Ben’s dad, Andy Velez, finds the record in Ben’s collection.

BEN: And he pulled that out and he he got like this look on his face of just I don’t understand. Like, I’ve never seen a record that was so profane, like what is this? He didn’t know what punk was, you know? And he turned it over and he read every lyric. And then he looked at me and he goes, this is really heavy stuff.

JIAYU: Andy is no stranger to punk’s message of fighting authority. In the 60s, he protested the Vietnam War. And when Andy became a father, he passed these anti-authoritarian values down to Ben and his brother.

BEN: He raised me attuned to the fact that, like, you couldn’t trust authority and that people were mistreated and the humanity of people was so important. And now he’s being confronted with like my generation’s version of it. I could tell that he was like, I don’t know whether to be shocked and protect you from this and send you to your room or to be really proud.

MUSIC STARTS

BEN: My dad, um you know, he was Puerto Rican. My grandfather um was super machismo and kind of a rough character. My dad ended up running away from home, you know, around 15 or so and was broke. But he spent his paychecks every week on records. And we’re a music family, like I was a record collector and DJ and stuff. I was and still am obsessed with the Clash. I consider Joe Strummer one of my gurus. He had a very famous quote about, uh, the true meaning of punk is the having exemplary manners toward your fellow human beings and stuff. So that was like my North Star. And I found that in grade school.

MUSIC OUT

RYAN: While Ben is coming of age in New York in the 80s, the city is starting to face a public health crisis – AIDS.

SARAH: The first public announcement of that is July 3rd, 1981, in The New York Times.

RYAN: Sarah Schulman lives in the Lower East Side. She’s a journalist and AIDS activist.

SARAH: The famous article “41 Cases of Rare Cancer Found Among Homosexuals in San Francisco.”

RYAN: At first, doctors think AIDS is “gay cancer.” Sarah continues to cover the growing AIDS epidemic – including pediatric AIDS, unhoused people with AIDS, and women’s struggles with getting treatment. She sees firsthand its brutality.

SARAH: Well, you know, people were really suffering. I mean, AIDS death is a terrible, terrible death. AIDS, what AIDS is is that your immune system doesn’t work anymore.

ARCHIVE (AIDS COVERAGE): A mystery disease known as the gay plague has become an epidemic unprecedented in the history of American medicine. That today from the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta. Topping the list of likely victims are male homosexuals who have many partners and drug users who inject themselves with needles.

RYAN: The queer community of New York does not have government support right away – they rely on community resources. Like a buddy system that was organized by the Gay Men’s Health Crisis – a nonprofit whose mission is “to end the AIDS epidemic and uplift the lives of all those affected.”

Unhoused people are also left behind by the system, even at homeless shelters. A political response is desperately needed.

JIAYU: During this time, Ben’s parents are going through a messy divorce. His dad Andy is a queer man and not fully out.

But Andy says he never would have left the marriage because of that.

ANDY: I was monogamous during the marriage. I’m very old-fashioned about certain things. I like to ruin one relationship at a time, *laughs* and I believe that God has a long white beard.

JIAYU: This is Andy talking to Sarah Schulman for the ACT UP Oral History Project – a collection of 187 interviews with members of ACT UP to show the rich and multi-faceted history of the organization.

ANDY: And I was totally crazy about my kids and really devoted, completely devoted to the home, even though she and I had really gone very divergent ways um and um she was just getting nutsier and nutsier.

JIAYU: Andy and his wife separate in 1982, but they don’t officially divorce for another 5 years. Ben is a preteen when his dad moves out of the house.

ANDY: I agreed to leave, although later, in her court papers, she accused me of abandoning the family. And included in the court papers that I had told her I was having a change in lifestyle that no longer included women.

JIAYU: Andy insists he didn’t say that. But he was frightened of what these rumors could mean for his custody battle.

ANDY: And, I was constantly being advised at the time by my peers – professionals – don’t come out to your kids. And, I wouldn’t have even known how to come out.

BEN: I came from a very dysfunctional family.

JIAYU: Here’s Ben again. Andy’s son.

BEN: You know, my mom was severely mentally ill. She was an addict. She was very abusive. My dad wasn’t really around and wasn’t able to stand up to her for this. And fathers, often with moms like that, end up abandoning their kids to the dragon because they just can’t you know, they can’t keep up with the fight, you know, And he wasn’t able to protect us. He was going through his own struggles.

MUSIC STARTS

BEN: You know, he was just from a different generation where um there was, I think, so much shame and no um words or language for being queer.

JIAYU: Coming out is especially difficult at the height of AIDS – when there’s a growing stigma about being gay.

BEN: My dad’s feeling was that he couldn’t be a dad of boys, and also be a gay man. Like, he couldn’t reconcile that. So it took him a very long time. You know, I remember my brother, who’s five years younger than me, you know, just confronting him and being like, dad, it’s been years like we know, like, you can just say it, you know, like everyone around us is gay. Like, we don’t care. It’s okay.

MUSIC OUT

FOUNDING OF ACT UP WITH ANDY’S STORY

RYAN: In March of 1987, a man named Larry Kramer makes a speech at the Gay and Lesbian Center in the West Village. He announces one of the first meaningful political responses to the AIDS crisis: ACT UP – the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power.

Public awareness campaigns about AIDS start to air.

ARCHIVE (AIDS awareness campaign): Good morning. Sex. It’s no longer a moral issue. It’s a matter of life and death. AIDS. It’s no longer a homosexual problem. It’s everybody’s problem. I’m Nola Roeper. And this morning on Best Talk in Town: AIDS, a nation in crisis.

RYAN: Then, on September 11, 1987, President Reagan makes a special television address to the country:

ARCHIVE (REAGAN): Good evening. Today, America faces a serious medical crisis, a spread of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome or AIDS. More than 40,000 Americans have been diagnosed as having AIDS, and there is no cure. That’s why I’ve declared AIDS public health enemy number one.

RYAN: This comes six years after the first public announcement of AIDS.

But is this too little too late?

MUSIC STARTS

JIAYU: While he’s estranged from his kids, Andy starts socializing more. He goes to gay bars like Uncle Charlie’s in midtown, where he meets people with AIDS. Then he sees signs to join a protest.

ANDY: I saw on a lamppost down in the Village, something um about a demonstration on Wall Street, um against the high price of AZT.

JIAYU: AZT is the only treatment for people with AIDS at the time. It costs users about $8,000 a year. Andy is still waiting on the custody decision. He worries about what might happen if he’s photographed at the demonstration. But something about the situation calls to him.

ANDY: And and this may have been because of what I was living through, with the divorce, I’m sure it had something to do with it – I thought, this is so terrible, that people are sick and dying and they’re dying alone and ashamed. Yeah, I definitely had a lot of identification with that.

JIAYU: Andy goes to the protest. Then, he goes to a meeting. And another meeting, until he’s a co-founder of ACT UP.

BEN: And at that point in his heartbreak of his marriage collapsing and his family collapsing and kind of what my mom did to the whole family system, um the AIDS crisis was arising in his community in which he had been closeted. All of a sudden, you know, he was in that community and he was in those first rooms where Larry Kramer started raising his voice and my dad was right there with him.

MUSIC OUT

RYAN: ACT UP calls itself “a non-partisan group united in anger and committed to nonviolent direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” The message resonates with people like Matty Ebert.

MATTY: I was 22 when I joined Act up, um and that was like 1987. And there were only, like, 50 people in the room.

RYAN: Matty had come to New York City four years ago for film school – and to escape his hometown in rural New York. He says the homophobia was brutal there, and he came to the city to be safe.

MATTY: Everybody had careers and things. We all had gone to art school. We wanted something else.

MUSIC STARTS

MATTY: But then AIDS happened and you just couldn’t not respond. I had to respond.

There was no fear involved. I was just like, I really want to do something and this is the only thing to do. So when you started going, I went to all those protests and demos. I went to meetings every week.

I was living in the East Village and there was a big homeless encampment that I remember people, people were becoming homeless because of their HIV/AIDS and there was no cure. And so people would just get it. And within a little while they’d be dead. If there was a protest and a body needed to be there, I would I would go.

The point of protest to me is civil disobedience. You have to break the law if you want change. There’s no other way around it. Like you have to lay down in the streets. I would not be alive today. We would not have human clinical trials. We would not have the medicines for HIV. Had we not broken every law, climbed every building. It’s not until you lay, we laid our bodies on the line that things, you know, that the homophobia started to break. You know what I mean?

MUSIC OUT

PROTEST METHODS

RYAN: ACT UP quickly makes themselves known. And by 1988, members are getting arrested over and over – for what they believe in.

Their bigger actions make the nightly news – especially when traffic is affected.

ARCHIVE (ANCHOR): This beautiful day started with trouble in Lower Manhattan. More than 100 people were arrested during a protest. Demonstrators were demanding more money in the war against AIDS. They brought rush hour traffic to a standstill. Tim Minton has details.

ARCHIVE (MINTON): [over chanting] The early show on Broadway today was packed [over chanting: ACT UP, FIGHT AIDS]. Thousands of financial center workers leaving subways and hundreds more in cars with nowhere to go caught the performance. It’s message was blunt: Spend more for research, treatment and education on AIDS.

RYAN: As their actions become bigger, ACT UP membership rises and rises.

DONNA: I would come to the Monday night meeting. Monday night meetings were huge. There’s five or six hundred people in a room.

JIAYU: Donna Minkowitz is a member of ACT UP in its early days. She’s also an early career journalist at the Village Voice.

DONNA: And the scene was also very, very social and, and um often very often very sexy. *laughs* You know, people, um, use the meeting for flirting and meeting people.

And I should say, you know, um the Voice was a paper where we were allowed to do what was known as advocacy journalism, which meant that we um we did not have to try to be strictly objective. So I was I was clearly very much on the side of ACT UP.

JIAYU: Donna says queer activists had been pretty tame for years. But the AIDS crisis is dire. Homophobia is rampant.

DONNA: Lots of people in the group had friends who lost their job, lost their income, um were fighting with insurance companies, couldn’t pay for medications even if they could get them. You know, yet they would come to demonstrations and fight. So the, the militancy was part of what was new.

ACT UP was willing to be to be out there. Something that I loved was ACT UP was willing to be radical on economic issues in a way I had not seen in other queer groups at the time. ACT UP was willing to talk about housing. ACT UP talked about universal health care. I was very excited by this, um this group of queer people that was, that was being very radical.

JIAYU: Donna is also excited by ACT UP’s commitment to a democratic structure. There might be people who have been in the group for a longer time, or might be more vocal. But there are no leaders.

DONNA: Even at um a demonstration when the police wanted to negotiate with someone, you know, the police will often say like, who’s you know, who’s your leader? And the line in act up was, you know, we don’t have any leaders. You have to talk to all of us, which um I found very empowering.

ANDY: And remember, we’re talking about people in some cases were either fighting for their own life or the life of someone very close to them, and this is a group they’re depending on, to come up with the information that is going to save lives. So, it was a very fraught situation.

MUSIC STARTS

JIAYU: They risk arrest. They wheatpaste posters all over the city. They harass elected officials.

ANDY: By that time, we were known enough so that um people didn’t want to see their photographs on posters, with blood on them. Um people didn’t want to see us walking around their office building, chanting their names. Um, we had learned the power, I mean it doesn’t matter how powerful someone is, in terms of what the world calls power. People do not like to be embarrassed. And they’re afraid of that. And, that was one of the things that we learned that really works.

JIAYU: Andy feels the urgency and despair of the moment. It drives him forward.

ANDY: People were dying every week. If they weren’t ACT UP members, they were related to ACT UP members. And, if you remember what the meetings were like, it got to be that the memorials were the first thing that were put on the agenda after a while.

BEN: He went to so many memorials and then he channeled both his rage about what happened with his family and all of the queer rage that he felt and um, you know, he was at the frontline, you know.

He was watching all his friends die. And, I remember him telling us then that, like, he got so used to everyone he loved dying that he stopped going to funerals and he stopped caring, which I think is a pretty common story amongst gay men at the time.

JIAYU: So Andy, and other ACT UP members, feel like there’s nothing to lose.

MUSIC OUT

INTRODUCE THE PARK: ACTIVISM, NEEDLE EXCHANGE, HOME FOR BEN

SOUNDS OF PARK AND BIRDS

RYAN: Tompkins Square Park is in the East Village, from 7th to 10th Streets, between Avenues A and B. It is also the epicenter of protest on the Lower East Side, especially in the 80s.

Here, AIDS activism focuses on the unhoused population of the park – many of whom are HIV-positive or have hepatitis C, or both.

MARGUERITE: So the two things represented the idea that this is our park.

RYAN: That’s Marguerite Van Cook – she’s an AIDS activist who lives a few blocks away from the park.

MARGUERITE: So the big chant from the activist crowd was, I’m sorry, going to have to curse. Who’s fucking park, our fucking park. So whoever was on the margins was also, you know, supposed to be in the park. And since a lot of them were HIV positive, then that became part of the the issue.

I mean, there was a kind of an understanding, I think, between some of my friends who were really strongly in ACT UP and what we were doing here, because it’s the same, it was the same battle. You know, we were trying to help people who were being marginalized and were, you know, going to die this horrible death.

RYAN: ACT UP’s biggest presence in the park is their needle exchange program – a crucial resource for areas with high drug use. Needle exchanges provide clean syringes for those who need them. In the East Village, there are a lot of drugs around.

MARGUERITE: And um it was kind of great for people, you know, because we were so it was one of the places where AIDS was being transmitted. So by allowing people to have clean needles um so they didn’t transmit the disease further, was this huge relief.

JIAYU: In 1988, Ben Velez is 17 years old. But he’s still just 5 feet tall, with a baby face. He’s going to Stuyvesant High School, located in the East Village. Ben is on edge for a lot of reasons.

BEN: The pressure of all of the abuse and the craziness of my family caught up with me. Um and I ended up not going to school for a year. Severely depressed. I got hospitalized. I was suicidal.

JIAYU: There’s also a lot of violence and homophobia.

BEN: I was closeted about who my dad was. I couldn’t acknowledge my dad on the street because he was pretty out at that point. He was getting involved in ACT UP.

JIAYU: In Ben’s hour of need, it’s the punk community that takes him in.

BEN: Tough, short, stout dude with a cane. And he took me under his wing and he was like, no, we’re going to protect this guy. And many years later, like late in our twenties or something I said, you saved my life. Like, you know, like I was going to be murdered one of those days. I said, Why? Why did you do that? He was always a short guy. And he said, You were shorter than me. And it made me feel good to actually be able to protect someone. And I was like, That’s it? That’s why I got to live? And he was like, yeah.

JIAYU: Ben finds family in the Lower East Side’s punk scene.

MUSIC STARTS

BEN: I kind of emerged out of my suicidal depression because I was being taken care of by this community. And I think that most of the people in the community came from pretty broken situations like I did.

These were, like um, real revolutionary people who didn’t want to pay rent and took over abandoned buildings when the Lower East Side was really bad. And um one of the coolest things there was a guy named Darby. Every night he went out and stole police lines. And he his entire floor was a wooden floor that was reconstructed because there was no floor. It was a rotted out building. His entire floor was Police Line: Do not Cross boards, like you couldn’t get more punk than that back then. And um I found esteem. I found pride.

If society didn’t accept you or if you were lost, no one was going to bother you here, myself included, you know that um, this very dangerous place was actually home, and um the people with the dollar signs in their eyes realized that this was the next frontier to be colonized.

MUSIC OUT

JIAYU: Around the rim of Tompkins Square Park, there are buildings with squatters living in them. The homelessness and drug use in the park make things difficult for the real estate developers who are eyeing these buildings.

Before they can do any development, they have to kick out the squatters. And to do that, they push to enforce a curfew in the park.

TENSIONS BUILDING UP: BEN AT THE RIOT

RYAN: The summer of 1988 is hot.

BEN: And it was real sticky. And so you had that that unbearable stillness of the air of like summer in the streets in the city.

RYAN: As tensions rise around Tompkins Square Park, Ben sees his punk community – his found family – under attack. He sees the gentrification the city and developers want to do to the area. And it’s horrifying.

Ben’s dad Andy taught him how to spot injustice in the world. And now he sees it happening right in front of him. Ben knows that he needs to do something about it.

Police begin to enforce the new curfew late in July. It doesn’t go well.

BEN: The weekend before the riots, they rode through on horses and they beat, they beat people, you know, and they were just like there was no there was no quarter. There was no you have to leave. They were like, oh, it’s 12 o’clock. Let’s fuck the freaks up now, you know, and um, and that’s how it went.

RYAN: But then, on August 6th, all hell breaks loose in the park.

SOUND OF SIRENS, A BOOM, LARGE CROWDS, PROTESTORS

RYAN: More than 400 cops, some in riot gear, descend upon the park and the surrounding area. But the protestors don’t go quietly.

BEN: So basically it just broke out all at once and they, they were charging in on horses and um, and you heard just the panic and you heard the screams of people being beaten. It was really it was like a war zone and um like without missing a beat, you know, we were all street smart. We were up and running. And um, you know, the whole goal was to get out of the park.

CHANTING CONTINUES

BEN: I remember like, you know, seeing my friends and we were like, it was like track and field. Like we were like leaping the benches, the park benches, it was like superhuman. We were just taking these, like flying Olympic like leaps over the, because the benches were in concentric circles and we were making it to the outer rims, you know, and then there’s a fence, you know, around the non entrance parts of the park. And I remember making it to the last thing and looking to my left and seeing my boy Andy and looking to and seeing his look of terror. And like looking to see what he was looking at. And there was just a wall of foot soldier cops. And they tackled me to the ground and they started beating me with sticks. I almost made it to the fence. You know, it was in the last concentric concrete circle. And I got tackled and I saw my friends, like running away. And all of a sudden I was in a dogpile of what I think was about 9, 10, 11, 12 cops.

CHANTING FADES

BEN: And they were holding me down and they were all beating me with their sticks. And um and they all had their badges taped.

My adrenaline was such that all I felt was tapping like I didn’t feel the beating. Like, I just felt like hard tapping all over my body. I must have been on my left side because my whole right side was pretty fucked up.

It was about 90 seconds of being beaten. And they were like, It’s our park, you fucking fag. Get the fuck out of you fucking faggot and fucking freak. I must have heard faggot and freak and homo like over and over and over.

I was there with my best friend um Alvin, He was one of the O.G. black punks of New York, too. I remember him, you know, grabbing me. He was always my protector. He was a big, tough guy from Harlem. And like, I was always, like, the little guy.

And he grabbed me, and I remember him, you know, getting in the cops faces and holding me up. I was like, all broken from having been beaten, you know? And he was like, Look at him. He’s a fucking child. He’s a little fucking kid. You’re all fucking pussies beating up on a little kid. And the funny thing about Alvin is that he was always hurting me by protecting me. He’s like throwing me around and like, getting in front of me and stuff.

CHANTING FROM RIOT [“It’s our fucking park” chant] fade up, then fade out.

JIAYU: The next morning, Ben’s mom sees his injuries.

BEN: She was like look at you, oh my God, look at you. And um I was like what? And she was like, look at you. And I was in so much pain and I looked down and my entire, you know, from my neck to my feet, like, was bruised, you know.

She was like we’re taking you to the hospital right now. And um as soon as we’re done at the hospital, we’re going to go to the ACLU because I don’t know what else to do, but we need to have you photographed. And um it’s funny, as much really crazy stuff and trauma that my mom had put me through, like she kind of rallied in that moment and she was like, Oh, no, this doesn’t stand. You know, like, we need to get you photographed before um um any of this fades. And I don’t know what else to do, but I know that you’re supposed to call the ACLU.

JIAYU: Ben’s lawyer thinks he has a case. And they file suit against the city.

Ben has friends from the riot who are also injured. One needs a wheelchair, some need physical therapy. But Ben’s case is unique.

BEN: But the only case that they could take was mine. Because I look like a child and the pictures were bad and it was going to look real bad for the NYPD to have pictures of having beaten a child so badly, you know, because I was 17, but I looked like I was 13. You know, I looked prepubescent. I was short, I was little. I had a child’s face.

MUSIC STARTS

JIAYU: Ben is right.

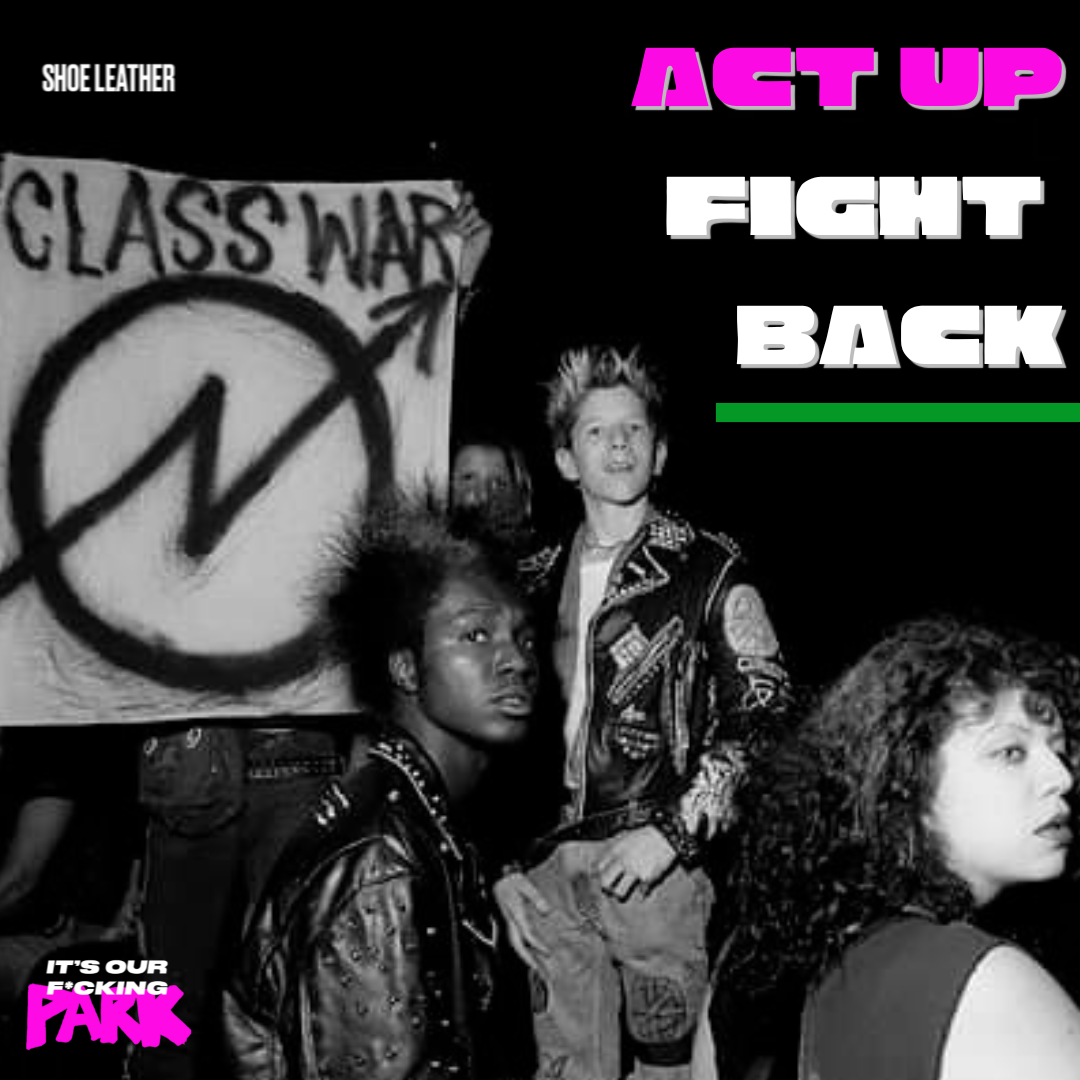

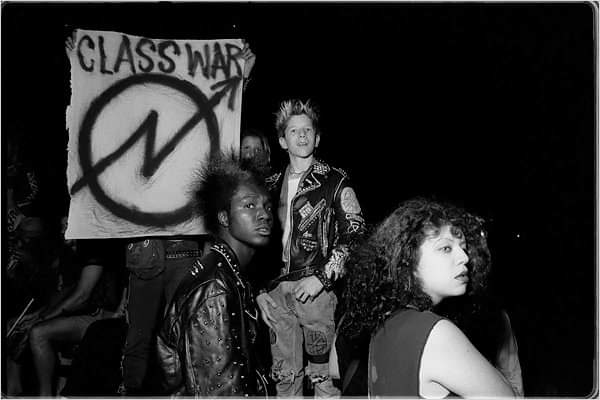

In a picture from the night of the riot, he looks much younger than his 17 years. He has blond spiked hair and a youthful face. He’s wearing a leather jacket with studs. His jeans are ripped in some spots, patched in others. He’s standing in front of a sign that says “Class War.”

BEN: And the city immediately said, we’ll settle.

JIAYU: At first, Ben doesn’t want to settle. He wants to have his day in court. But his lawyer advises him to take the settlement. So Ben can move on with his life and go to college.

BEN: All of this, it was a pittance. It was $15,000, but we were poor and I gave most of that to my mom. And, you know, it helped me. I had mostly a scholarship, but it helped me with money for college and, um you know, helped my mom in our household at the time.

JIAYU: The only extravagant things that Ben buys with the settlement money are music-related. He wants to become a DJ, so he buys his first turntable.

BEN: I bought that and I bought my mom a coffee maker because um she was broke and she was working a real hard-on-her-feet job at the time, and our coffee machine had broken and I thought that was like a nice symbolic thing to do, is buy my mom a coffee machine, you know.

MUSIC OUT

BEN AND ACT UP TODAY

RYAN: For a few years after the riot, Ben and his dad Andy still don’t talk much. But Andy is keeping journals – and writing about his son.

BEN: We lived across the street from him. And so we would see him in the neighborhood. And he I think, you know, he writes about it in his journals, watching me descend into going from being a sweet boy to someone with, you know, struggling with mental illness to um a tough street kid. You know, he saw me sort of and kind of just was like in his journals. He talks about I hope he’s going to be all right and it’s out of my hands and stuff.

MUSIC STARTS

BEN: We got back in each other’s lives um in my twenties. And um I realized it was really important to forgive my dad for some of the stuff that had happened. You know, not being able to save us and kind of just being powerless with my mom and kind of giving up. But, you know, we just kind of buried the hatchet and realized it was important that I have a father and that he have a son and made up for lost time and stuff. Then he was able to start to tell us the story of ACT UP.

And there’s a very happy picture of him after his relationship with my mom had collapsed and he’s wearing his favorite powder blue um Christian Dior eighties jumpsuit and some I think he’s wearing his like obnoxiously like bright red eighties sunglasses. And he’s got a big smile and he’s got his hand on his hips. And it’s one of those pictures where he’s clearly so queer, but we didn’t know.

JIAYU: Andy becomes more open and comfortable with his identity over time. But there’s a little bit of shame that he never lets go.

BEN: Somewhere in his mind, he had to compartmentalize being a father of boys and being a gay man. He didn’t understand that they could coexist.

JIAYU: In 2019, Andy dies after a serious fall…

BEN: You know, to his death, he carried that generation shame around queerness, which was really heartbreaking.

MUSIC OUT

RYAN: Ben and Andy become so close that, later, people are surprised to learn they were ever estranged.

BEN: Um when he died, a whole bunch of older gay, you know, gray haired and white haired gay men said, well, you have a bunch of aunties now because, you know, you know, you lost your dad, but we’re your aunts, you know.

JIAYU: Today, Ben is a therapist. He meets lots of people who know – and admire – Andy.

BEN: So I feel like my dad’s hand is in the fact that I work a lot in the queer space there therapy wise.

You know, but there was always this dichotomy of your dad’s hero and us having this complicated relationship with his activism. You know, that, like, somehow as kids, we felt like his activism robbed us of fatherhood.

MUSIC STARTS

RYAN: In 2023, new medicines mean HIV is no longer a death sentence. But ACT UP doesn’t go away.

CHANTING BEGINS

RYAN: On the eve of its 36-year anniversary, the group is taking on a new kind of fight.

A book – a book that ACT UP believes promotes aids denialism.

2023 ACT UP PROTEST: “Say it loud, Say it clear, AIDS denial’s not welcome here”.

RYAN: They have a big digital sign using the same graphics that the generation before used. And the protestors are chanting the same chants.

2023 ACT UP PROTEST: “What do we do? ACT UP, fight back” “What do we do? ACT UP, fight back” “What do we do? ACT UP, fight back”

MUSIC OUT

CREDITS

MUSIC STARTS (SHOE LEATHER THEME MUSIC)

JIAYU: Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by Ryan Kilkenny and Jiayu Liang.

RYAN: Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Rachel Quester and Peter Leonard are our co-professors. Special thanks to Columbia Digital Libraries, Professor Dale Maharidge, Ron Kuby, Clayton Patterson and Paul DeRienzo.

JIAYU: And thank you to Brandon Cuicchi, whose time and energy were crucial to this episode. Audio from the ACT UP oral history project provided courtesy of Sarah Schulman.

RYAN: Shoe Leather’s theme music – ‘Squeegees’ – is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller, remixed by Peter Leonard.

Other music by Blue Dot Sessions.

JIAYU: Our season four graphic was created by Lina Fansa and Ghiya Haidar.