On March 25, 1990 eighty-seven people died when the Happy Land Social Club burned. After Julio Gonzalez argued with his girlfriend he bought a gallon of gasoline and set the club on fire. Until the Oklahoma City Bombing in 1995 the Happy Land fire was the deadliest mass murder in US history. Though the tragedy has since slipped through the cracks of collective consciousness, for those who lost loved ones in the fire, it remains a part of their lives. This is a story of community, loss, memory, and resilience. This is Happy Land.

TRANSCRIPT

KARA GRANT: What do you think of when you hear: deadly mass murders in the 1990s?

JACK ROSSITER-MUNLEY: The two things that first come to mind are the OK City bombing in 95 and, uh, Columbine, the school shooting in ‘99.

KARA: When we started looking into New York in the 90s did you ever expect to come across one of the deadliest mass murders in American history.

JACK: Absolutely not.

SHOE LEATHER THEME MUSIC IN

KARA: I’m Kara Grant

JACK: And I’m Jack Rossiter-Munley. This is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today.

KARA: In season 1 we look at New York in the 90s. This is Happy Land.

SHOE LEATHER THEME MUSIC OUT

KARA: This is it.

JACK: This is it?

KARA: It’s an income tax.. what

JACK: In- uh, I’m guessing it’s a place that does your taxes?

MUSIC IN

KARA: We’re standing outside a storefront in the Bronx on a cold day in February, because thirty years earlier, this was the site of one of America’s deadliest mass murders.

JACK: In the early hours of March 25, 1990, thirty-five-year-old Julio Gonzalez argued with his girlfriend at the Happy Land Social Club. A bouncer kicked him out. Enraged, he bought a dollar’s worth of gasoline. Returned to the club. And lit the only known entrance and exit on fire.

JACK: In the late 80s, illegal social clubs like Happy Land were all over New York City. They were dark, cramped, and didn’t adhere to fire codes. People knew they were dangerous. But they were still places where immigrant communities came together and partied.

KARA: The club filled with smoke. And the people inside were unable to see. Unable to breathe. Unable to escape. Until the Oklahoma City bombing that happened in 1995, the fire at Happy Land was the deadliest act of murder in US history.

JACK: But Kara and I had never heard of this fire. We’re both in our late 20s and not from New York.

MUSIC OUT

JACK: But even when we talked to people who are older than us, who grew up in the city – they also had no idea.

SOUND: Walking off the subway into the Bronx – sirens and old school hip hop playing on the street

JACK: We figured if there was one place where people would remember Happy Land, it would be in West Farms, the neighborhood in the Bronx where the club used to be.

WOMAN OUTSIDE STORE: I don’t know nothing about that. ‘Cause I don’t live here. I only work here. This is new.

RICK: Not around here, yo. It’s hard to find people who know about that stuff here. That happened what 89 I think? 87?

KARA: 1990, yeah.

RICK: Yeah not too many people know about that too much, you know. It’s changed a lot around here that’s why. A lot of people did die, you know what I mean? 87? It was some boyfriend. It was about a boyfriend that got jealous and he went inside the door and he locked it.

KARA: A lot about the neighborhood has changed in thirty years. Besides the tax place, there’s a Kennedy Chicken on the corner and a barbershop next door. But a lot has stayed the same, too. There’s still the same public school across the street, and a Puerto Rican gift shop that’s been in West Farms for over 40 years.

KARA: We’re doing a story about the Happy Land fire that happened. Do you remember anything about it?

GIFT SHOP OWNER: Oh, no I was, well, I was a kid. Not really. Well him, he doesn’t know english much though.

JACK: We found a few people who remembered the night that Happy Land burned. But their memories were foggy after 30 years.

GIFT SHOP OWNER: Happy Lando? Okay, yeah, he remembers. Yeah he here got back from a show and he saw all the cops and the fire department.

MAN ON STREET: I remember like yesterday, because I always come out to get coffee in the morning and I saw a lot of people there. That was sad, very sad. ‘Cause, 87 people, 86 it hurts.

RICK: It was like a Hondurian party, you know what I mean. My friend had two cousins in there that died that day matter of fact, I remember that. That’s what I remember.

KARA: Did you know anyone?

MAN ON STREET Yeah a few friends, maybe two or three of them. I used to —

JACK: He was the only person around who really remembered Happy Land. What it used to be.

JACK: Did you ever go to happy land before the fire?

MAN ON STREET: Yeah I went once with one of my friends that die in there, but I didn’t like it because it’s always too many people for a small place, you know? Too many.

MUSIC IN

KARA: People remembered it in bits and pieces; it seemed to have slipped through the cracks of collective consciousness. But we knew that, for those who lost loved ones in the fire — it would never leave them. It would be part of their lives, and their family’s lives, forever.

MUSIC OUT

JACK: On a slim strip of land between Southern Blvd and Crotona Parkway, there is a half-hidden memorial.

MUSIC IN

It’s a small obelisk in a square of brickwork and a few benches, surrounded by a fence with padlocked gates. Plastic flowers ring the fence top. There are no signs on the outside of the fence, just a plaque within that lists the names of those who lost their lives.

KARA: You could walk past without ever knowing what it was.

MUSIC OUT

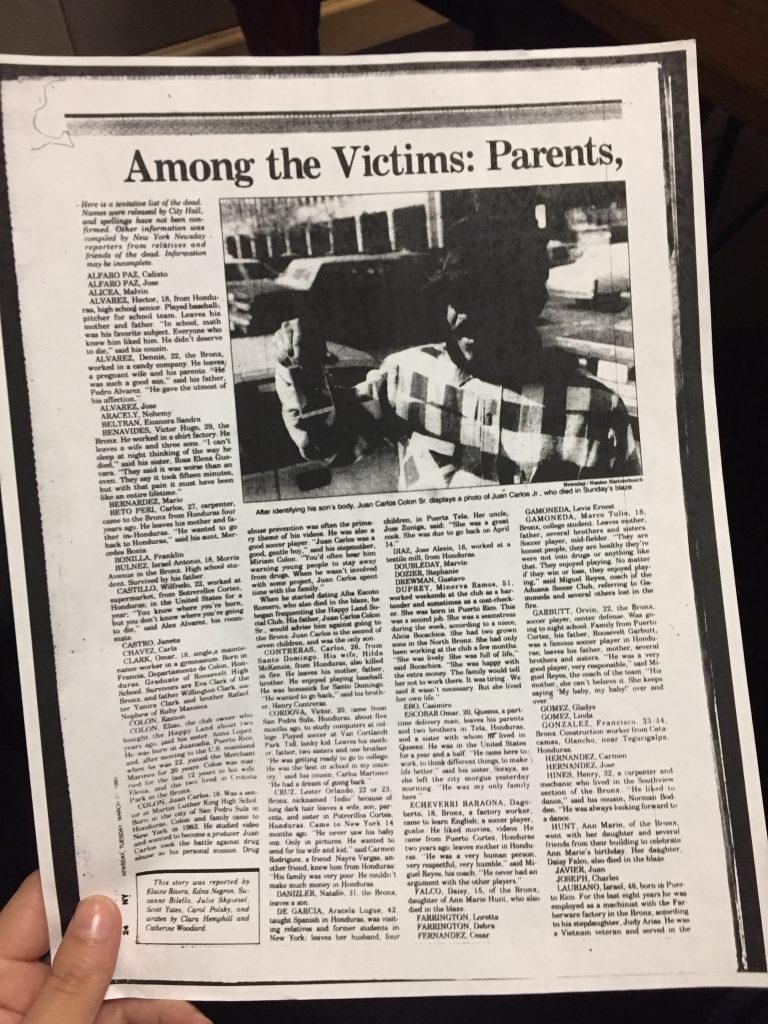

But in 1990, the fire was big news.

ANNOUNCER: NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw

JANE PAULEY: Good evening I’m Jane Pauley sitting in for Tom Brokaw. A city mourns, families grieve, and a man is charged with mass murder setting the fire that killed 87 people in New York City early yesterday.

JACK: A year and a half later it was the inspiration for an episode of Law and Order.

SOUND: Law & Order Theme

LOGAN: I’ve never seen this many, have you?

CERRETA: Not in civilian life.

LOGAN: What was this place?

OFFICER: A social club.

JACK: And even showed up in music. Jay-Z mentioned it in a song.

JAY-Z: Cat be him, El Cap-i-tan/The fire I spit burn down Happyland [sic]/Social Club, we unapproachable thugs

JACK: And so did Duran Duran.

DURAN DURAN: Coat check girl up in Happyland [sic]/Has a violent row with a Cuban man

KARA: But that’s where the nuance ends for Happy Land. Now all that’s left even in the neighborhood where the club once stood, are vague memories . You can even see the facts blurring and the myth forming in those early news reports and songs. Duran Duran gets the number of victims wrong —

DURAN DURAN: The sin is that 89 died/89 dead! 89 dead!

— and only a few basic pieces of information are consistent: a raging ex-boyfriend set the club on fire and locked the door behind him.

MUSIC IN

JACK: Julio Gonzalez was convicted of 87 counts of murder and 87 counts of felony murder. He was sentenced to 25 years to life for each. Court documents from 1991 list the events of that night in detail. After he lit the club on fire, Gonzalez got on a bus, put on his portable cassette player and even though it was the middle of the night, sunglasses. Then he cried. When he got back to his apartment, he told his friends that he had killed his ex-girlfriend.

MUSIC OUT

JACK: But he hadn’t.

MUSIC IN

KARA: Lydia Feliciano, the one person he actually meant to kill that night, was one of the few people who made it out of the club alive.

JACK: When we first found out that Lydia survived, we knew we had to try and find her. And try we did.

KARA: The latest news report we could find that mentioned her said she was on dialysis for kidney failure. It was also over five years old.

JACK: So we started calling every Lydia Feliciano we could find on the internet.

SOUND: Phone ringing

AUTOMATED VOICE: This mailbox is not currently accepting messages

AUTOMATED VOICE MACHINE: 880 is not available please leave your message after the tone.

SOUND: Phone ringing

ANSWERING MACHINE: Hello, Carmello can’t come to the phone right now but please leave your name and number and he’ll get back to you as soon as he can.

KARA: Hey Carmello, um, this is Kara Grant, y-you came up in a search related to Lydia Feliciano.

JACK: It didn’t work out.

KARA: We also looked for anyone who might have more information about the fire and its survivors.

TEOFILO “TIO TEO” COLON JR.: My name is Teofilo Colon, Jr otherwise known as “Tio Teo.” I have a website which is pretty much a blog called Being Garifuna, chronicling the news or happenings of the Garifuna ethnic group. Do you know what the story is?

MUSIC IN

KARA: I would like you to tell us…

JACK: Yeah! Tell us.

ALL: [Laughter]

KARA: As you understand it.

TIO TEO: The Garifuna people are people of African, Carib-Indian and Arawak-Indian cultural heritage that melded together on the island of St. Vincent in the 1600s and 1700s.

JACK: For his site, Tio Teo meticulously researched all the victims of the Happy Land fire to determine which were of Garifuna descent. Underground clubs like Happy Land often served specific ethnic communities. Happy Land was mostly Honduran but it also hosted Dominican and Puerto Rican patrons.

KARA: Almost half of the people who died at Happy Land were Garifuna according to Tio Teo’s research.

MUSIC OUT

KARA: He also has a personal connection to the fire.

TIO TEO: My cousin Juan Carlos Colon, Jr. was one of the victims of the Happy Land fire. Apparently was- he had gone to the party with his girlfriend who was also one of the victims. And as they were going through the bodies they were in an embrace.

KARA: We asked Tio Teo if he knew of anyone else in the community who lost someone in the fire that night.

TIO TEO: I can forward you their information if you want to reach out to them and ask them about their experience with the Happy Land fire.

JACK: That would be great.

KARA: Yeah that would be great.

SOUND: Coffee shop noises

KARA: We met Thelma Gomez at a busy Starbucks near Columbus Circle. She’s 37 years old. She was wearing a burgundy coat and had her hair in long, black braids. But the first thing you really notice is her eyes. She has Ariana-Grande eyes. They’re big, brown, and sparkly.

THELMA GOMEZ: My name is Thelma Gomez. My mother worked at a club. The club’s name is Happy Land Social Club.

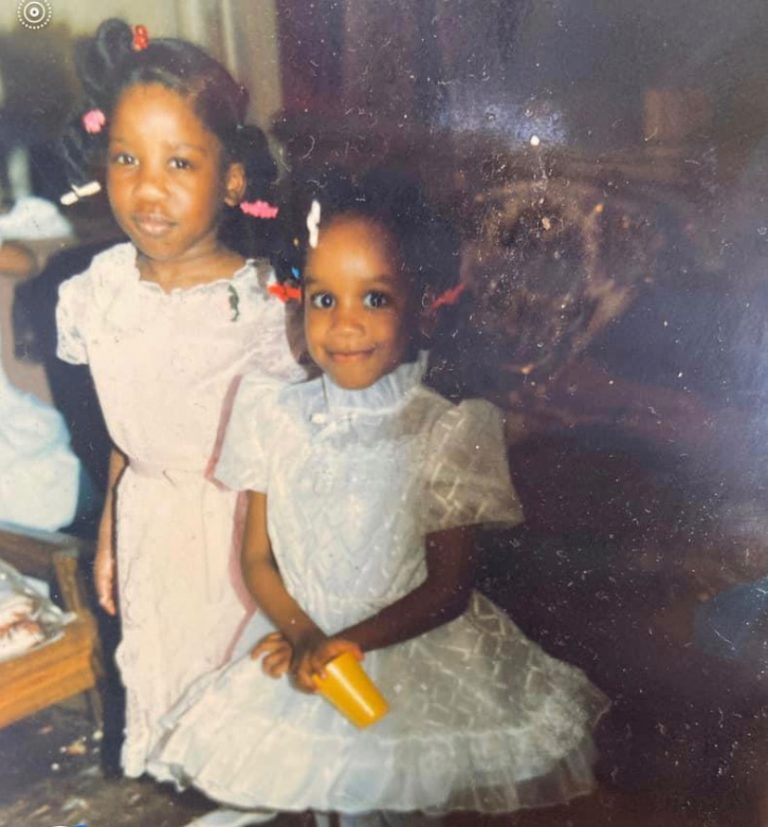

KARA: Thelma was only eight years old when her mom died. But she remembers her really well. She used to put her and her sister in pretty dresses and give them special hairdos. She especially remembers the food her mom used to make.

THELMA: She loved to cook. So, um, you know, she would always make Sunday dinners um BBQ ribs, yellow rice, she liked her vegetables, cauliflower, broccoli, yeah.

JACK: Justa Gladys Crisanto, Thelma’s mom, was 26 when she died.

MUSIC IN

She worked as a bartender at Happy Land. She sometimes took Thelma and her other children to the club when she was working.

THELMA: Happy Land was a dark club. Like you kinda could sense it wasn’t safe.

KARA: Less than a year and a half before the fire, the club was cited for numerous building and fire code violations. They didn’t have emergency exits, fire alarms, or a sprinkler system. But they kept operating as usual.

JACK: The club was two stories. The entrance, the one that was burned, opened to a narrow staircase that led to the top floor. That’s where the dance floor was, and the bar. Probably where Justa would’ve been stationed.

KARA: The night of March 25th, 1990, Justa left Thelma with an aunt. Thelma’s memory of that night is jumbled. At eight years old, it was hard to understand what was happening.

THELMA: My aunt was crying and the news was on and they said it was you know what they were reporting that Happy Land burned down and so I’m like, well, Where’s my mom? And, you know, nobody would answer me. And what I remember now is getting dressed up with dark clothing, about a week later and going to her funeral. And that was the last time I saw my mother.

JACK: Thelma has a photo from that day. Her mom’s open casket. You can only see a sliver of her face, but she looks peaceful. Like many of the victims, she died of smoke inhalation. She’s wrapped in white fabric. Beside her, there’s a crucifix.

THELMA: I didn’t know the devastation, until then, that 87 people were killed. My mother was one of them and my life would change forever.

JACK: After her mother died, Thelma went into foster care. She lived with a family in the same neighborhood as Happy Land. She went to school across the street from where the club used to be until she was in eighth grade. That meant that every day she had to walk past the building where her mother died. The front remained blackened and burned for years.

THELMA: A lot of my life didn’t make any sense. Like, how do I end up right across the street from this place? I think that’s why I was sad every day. Because I had to see where my mother lost her life.

KARA: But that wasn’t even the worst part. After the fire, emergency service workers needed somewhere to put the bodies, so that their loved ones could identify them. The closest place that was big enough was that very same public school.

JACK: Thelma had to walk through the school doors every day knowing they were the same doors her mother’s body had been carried through hours after she died.

THELMA: I felt like there was a disassociation of the person who was going to school, the child who was going to school and the real me that was hurting inside because I didn’t have my mom. It was rough, it was rough.

KARA: Thelma finished middle school and started working. She ended up getting her GED. She also ended up in two bad marriages, something she attributes to losing her mother. Her protector.

MUSIC OUT

THELMA: I got married. My husband was abusive. I left him. And I got married again. My second husband was abusive. And I, uh, divorced him. And now I’m single.

KARA: Men are shit! No offense.

THELMA: You’re absolutely right!

BOTH: [Laughter]

JACK: Losing her mom changed the course of Thelma’s life. Which made us wonder, did she know anyone else who lost a parent at Happy Land?

KARA: So there were a lot of kids who lost parents. Is there any sense of community there-

THELMA: I thought we were the only children, my siblings and I, that lost parents because, you know, we go to the memorial. We’ve been on TV and I’ve never heard of children say my mom died there. This is the first time I’m hearing that there were other children of the deceased.

KARA: Just now?

THELMA: Yeah.

KARA: Really? You’ve never met any other…

THELMA: No, no, no.

JACK: Even, like, going to school there wasn’t anybody who said anything or…?

THELMA: No, no.

JACK: We couldn’t believe what Thelma had just told us. All this time, she thought she and her siblings were the only ones who had lost a parent in the Happy Land Fire. We were the first to tell her that there were others.

MUSIC IN

The reason we were so surprised is because the night before Kara and I first met Thelma, we had gone to the basement of one of the Libraries at Columbia University.

MUSIC OUT

JACK: I am looking for the old Journalism School Masters theses. I know they’re kept somewhere in this library.

LIBRARY ATTENDANT: They might be behind the reserve desk, let me make sure that we have – that we’re able to give access to them.

KARA: The whole library is pretty much in the basement. I really like this library because it’s like a true mid-century modern institutional space. With weird couches that are built into the walls, and dark carpet, and a fun spiral staircase that leads you down to the level where the old masters theses are.

JACK: They’re tucked away in the back corner on shelves that look like they probably haven’t been touched for about a decade.

JACK: Do you think “Major Papers” —

KARA: Yeah.

JACK: are different than theses

KARA: No.

JACK: –or did they just start calling them that?

SOUND: Rustling paper.

JACK: Yep and there we go, Maurice M. Krochmal “Tierra Felize, Tierra Triste: The Consequences of the Happy Land Fire”

JACK: It turns out we weren’t the first Columbia students to look into Happy Land. In 1995, a student at the J-school named Mo Krochmal wrote his masters thesis on the fire.

Mo’s writing was by far the most detailed account we’d found. As we read through his thesis, one piece of information stood out to us: over 90 children lost a parent in the fire.

KARA: Which made sense to us, intuitively. 87 men and women — many in their 20s or 30s — they had to have left children behind.

JACK: In fact, the first person we spoke to when we visited the Happy Land memorial was an old man leaning on his cane just outside its gates, Francisco Calix.

FRANCISCO: Ooooh yeah. I had, I hd a my sister in law. A sister in law that died there too. That was my brother’s wife. Yeah, and she left uh, she left four kids.

KARA: We also read news stories about a young woman who lost her mom in the fire and was now searching for her long-lost sister. It just never crossed our minds that Thelma wouldn’t know anyone else who lost a parent at Happy Land.

THELMA: It’s been 30 years. And ‘til, up until today I thought we were the only children survivors of that event.

KARA: How do you feel hearing that you’re not?

THELMA: I don’t believe it. I would have to meet someone. I believe that by now I would have known if someone’s parents died there.

MUSIC IN

KARA: With Happy Land, there’s just this sense of we don’t talk about this. It came up with Tio Teo, when he told us that his cousins never speak about the brother that they lost. It came up again with Thelma. Then we thought back to the memorial site itself. Sealed off by a fence and padlock, lost between two busy streets. Something about this specific event seemed to be buried in time.

JACK: We wondered – if Happy Land had been on 86th street and Park Avenue and its patrons were New York’s elite: white, wealthy, not immigrants. How would it be remembered then?

MUSIC OUT

JACK: Every year on March 25th, there’s a gathering at St. Thomas Aquinas church in West Farms.

THELMA: It’s beautiful, you know. I usually go up and say my mom’s name and then they have a procession where they walk down and they light candles and say a prayer. It’s really nice.

MUSIC- Lord’s prayer being sung in the Garifuna language

KARA: The community has the chance to grieve together, singing the Lord’s Prayer in the Garifuna language.

MUSIC – Lord’s prayer being sung in the Garifuna language fades out

Thelma hasn’t been to the service in years. But this year she was really excited to go, and this time, she knew who she would be looking for. The other kids – the ones that were just like her.

KARA: Would you be interested in meeting any?

THELMA: Yeah, of course, of course. I’d want to know how it worked out for them because I know it was rough on us.

KARA: If you’d had that community support how would it have changed?

THELMA: It would have made a difference, I think. You know, like, when I was going – healing from my abusive marriages I reached out to support systems that were women who had been through the same situation and it helped. So that’s why I know it would have helped. But that wasn’t the case.

JACK: We made plans to go to the memorial with Thelma.

THELMA: I’m going to take a picture with you guys at the memorial because I’ll be all dolled up!

JACK: Oh very nice!

KARA: But of course, the memorial was cancelled.

ANDERSON COOPER: Shockwaves were felt here in New York when our next guest said he was absolutely considering a shelter in place order. He’s the Mayor of New York City, Mayor Bill deBlasio —

KARA: As a global pandemic forced the city into lockdown.

COOPER: — Mayor deBlasio thank you so much for being with us. What is the —

SOUND: Phone rings…

THELMA: Hi

JACK: Yay!

THELMA: How are you?

KARA: Good how are you?

THELMA: I’m great, I’m great. [laughs] confined to my quarters. You know, we’re home. We’re safe. We’re stocked up. We’re fully stocked up, we’re good —

JACK: Thelma would have to mourn the 30th anniversary of her mother’s death from a distance.

MUSIC IN

KARA: The last time Thelma went to the memorial was five years ago. There’s a photo of her and her family from that night. She’s wearing a tight black-and-white patterned dress and holding a cheetah print clutch. She has an umbrella in one hand, and there’s a bouquet of flowers tucked in her other elbow. She’s smiling, big.

JACK: She’s with her two daughters, both in down puffer jackets. One black, one pink. Sometimes Thelma and her family would give interviews. She was standing in the rain, in front of the lights and cameras, on the anniversary of her mother’s death.

She was also more than eight months pregnant.

THELMA: It was raining so nobody could tell that my water had broke. And my family was with me. And they’re like, what’s wrong because I started crying. And I’m like, I think my water broke and they look down and they were like that could be rain. I’m like —

MUSIC OUT

— no, this is my fourth child, like, my water broke.

KARA: Thelma started going into labor at memorial. It was around 8 o’clock when she and her family piled into a cab and rushed to the hospital. She gave birth to her son Caleb at 12:06 am, March 26th, the day after the 25th anniversary of her mother’s death.

THELMA: The fact that he was born on the 26th I remember at first feeling disappointed but then it made perfect sense to me. Why would he be born on the 25th? The 25th is already set aside for, you know, my mother’s death and so that’s her day so that’s her day and the 26th belongs to Caleb.

MUSIC IN

JACK: Now on the 26th, Thelma celebrates her son’s life.

CELL PHONE VIDEO OF CALEB’S BIRTHDAY: Are you 1, are you 2, are you 3, are you 4, are you 5!?!

JACK: Cooking for him the same way her mother cooked for her.

THELMA: And, um, for Caleb’s birthday, I made baked chicken, yellow rice, salad, and stuffed shells. As soon as I served the plate the food was gone.

THELMA: Can you come please? I would like you to say hi to someone.

KARA: How was your birthday yesterday?

CALEB: Good.

THELMA: What was your favorite part?

CALEB: Uh, the food.

THELMA: The food? See I told you guys!

KARA: Once her children learn about what happened to their grandmother, Thelma feels like they grow closer.

THELMA: I’m the type of mother I am because I lost my mother when I was a very little girl. Something usually so important happens in our bond and our relationship. They kind of understand me a little bit better.

JACK: Caleb still doesn’t know how significant his birthdate is. Thelma’s going to wait to tell him about his grandmother. She’s thinking when he’s seven he’ll be old enough to understand.

KARA: Caleb, like his siblings, will grow up knowing the story of the Happy Land fire. For him, it won’t be just a “Tax place,” or a Kennedy Chicken, or a fenced off lot with paper flowers.

JACK: The painful history of that place already shapes his life. It informs the way his mother raises him. And it will always be a part of who he is and who he becomes.

KARA: Thelma has yet to meet any of the others who lost a parent in the fire. But, there’s always next year.

THELMA: Say “Bye Jack, bye Kara.”

CALEB: Bye Jack, bye Kara.

KARA: Bye!

JACK: Bye Caleb!

CALEB: Bye

MUSIC OUT

MUSIC – SHOE LEATHER THEME IN

CREDITS

KARA: Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by me Kara Grant

JACK: And me Jack Rossiter-Munley. Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Dale Maharidge is our co-professor. Keshav Pandya is our technical advisor.

KARA: Special thanks to Columbia Journalism Librarian Kristina Williams, Columbia Digital Librarian Michelle Wilson, Peter Leonard from Gimlet Media, Rachel Quester from The Daily, Emily Martinez and David Blum from Audible, Susan White from Garage Media, Nate Di Meo from The Memory Palace, Jonathan Hirsch from Neon Hum Media, Clint Schaff from the LA Times Studios, and to Stuart Karle for his legal advice.

JACK: Thank you especially to Mo Krochmal for all the work he did on the Happy Land fire back in 1995 and for giving us the best tour of Inwood two journalism students could ask for.

KARA: Shoe Leather’s theme music ‘“Squeegees” is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller Other Music by Blue dot sessions.

JACK: For more about this episode and Shoe Leather, go to our website www.shoeleather.org To stay up to date on the latest Shoe Leather happenings, follow us on social media. We are on facebook at facebook.com/ShoeLeatherCast and on instagram and twitter @ShoeLeatherCast.

MUSIC – SHOE LEATHER THEME OUT

© Kara Grant and Jack Rossiter-Munley, 2020.

To contact the authors of this podcast please reach out by email.

Kara: karagrant95@gmail.com. Jack: jrossitermunley@gmail.com.