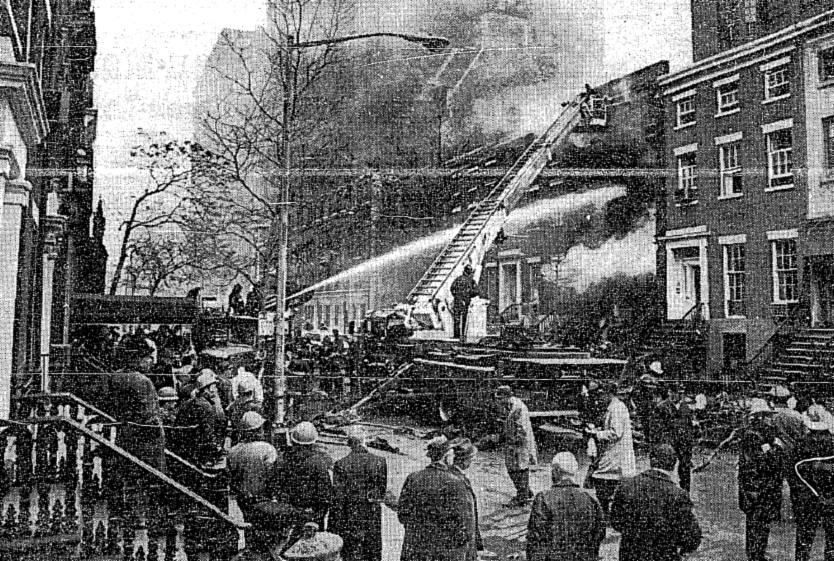

On March 6, 1970, a townhouse in New York City’s Greenwich Village blew up. After unearthing large quantities of dynamite in the wreckage, local officials determined that the townhouse’s basement had been used as a makeshift bomb factory.

Three people died in the explosion and the two women who survived would be on the run for the rest of the decade. They were a group of white, upper class, twenty-somethings, who only a few years before demonstrated in peaceful protest against the Vietnam War.

What drove them to start building bombs in the basement of a Greenwich Village townhouse? The answer begins on college campuses in the late sixties.

Transcript

ARTHUR LEVIN:

And, you know, I was certainly questioned by the FBI. When they were looking for some answers, in hindsight, I, there were signals of something amiss was going on in the building.

DAVID HOLLERITH:

That’s Arthur.

ARTHUR:

Right, Okay, so… my full name is Arthur. Aaron, double aaro n Levin, le VI, N.

HOLLERITH:

That building Arthur’s talking about, number 18. Its the one next door.

He lives in Greenwich Village on West 11th.

He’s been on this street since the sixties. Picture a redbrick townhouse, white windows, stone staircase, three stories tall and four counting the basement. In Baltimore they call it a rowhouse, in New York, It’s a townhouse.

Arthur’s not just a longtime Villager, either. He’s actually president of Village Preservation, that’s the neighborhood’s historic preservation society. And in 1970, while so many other places in the city struggled, this neighborhood felt vibrant.

ARTHUR:

Yep. the block was really interesting… It was sort of old, not overwhelmingly artsy, but certainly a little bit artsy. And, and, you know, oriented towards the entertainment world.

HOLLERITH:

Actually, Arthur’s street, West 11th. Was pretty star-studded. The producer, Mel Brooks, and his wife Anne Bancroft owned a place down the street. Dustin Hoffman, lived two houses away. Which is funny because Hoffman played opposite to Bancroft in the movie The Graduate. Oh and, Bob Dylan, stayed a few blocks South

HOLLERITH:

Arthur lived next door to the Wilkerson’s.They.. weren’t famous, but they had money.

ARTHUR:

She was a Brit. He was an American, he owned. I think radio stations in the Midwest. their house was quite elegant. In terms of furnishings… They were very pleasant, upper class neighbors.

HOLLERITH:

They also traveled a lot. And so, it wasn’t unusual for Arthur to see people he didn’t know hanging around the house.

ARTHUR:

What was unusual was that all the shades were down all the time. And I think I may have seen the folks carrying in the explosives they were carrying in boxes.

Music – Squeegees

NEWSREEL:

Investigators first thought the explosion was caused by leaking gas but as their search continued they began finding evidence of explosives.

HOLLERITH:

What Arthur didn’t know – was that these strangers were building bombs in his neighbor’s basement. They had waged war against the U.S. government.

NEWSREEL:

A federal grand jury in Detroit today charged the 13 top leaders of the weathermen with plotting to bomb public buildings in Chicago New York, Detroit and Berkeley California.

—- —-

I’m David Hollerith

This is Shoeleather.

Music in

HOLLERITH:

We dig up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today.

This season, we’re back in the 1970s.

We’ll look beyond bell bottoms, disco and mood rings to explore what made this decade so notorious in New York’s history.

A time when the Big Apple went by a far more sinister nickname —

CBS MORNING NEWS:

Unionized employees of New York City who face dismissal have put out a booklet describing Fun city as fear city.

HOLLERITH:

Crime was rising – by the mid 70’s, on average, there were four murders a day in New York – today it’s closer to one…

And The Bronx was burning.

HOWARD COSSEL:

That’s a live shot again

HOLLERITH:

People were fleeing the city – nearly one million left by the end of the decade. They took their money with them. In that time, New York wasn’t just broken – it was broke.

Beneath its financial issues, protest was in the air, it had been bubbling up since the sixties.

DEMONSTRATION NEWSREEL:

The estimate 125000 Manhattan marchers include students, house wives, beatnicks, doctors, teachers, priests and nuns.

HOLLERITH:

Other revolutionaries turned to dynamite to demonstrate opposition.

NEWSREEL:

The Switch Board at the Capital Received a Phone call. A man’s voice said a bomb would off in the building in half an hour.

HOLLERITH:

Through the seventies Bombings were high in the U.S. Especially for political reasons,

NEWSREEL continued:

There was alarm that other bombs might still be hidden in the capital.

HOLLERITH:

From January 1969 to October 1970, there were 370 bombings in New York City. That’s more than one bomb every other day for almost two years.

Most explosions were small. A few ended in casualties, even death.

Music In

This is the story about one of those bombings in New York City during the seventies. One that went wrong.

This is season two – New York Drop Dead. Episode – Nasty Weather.

Music OUT

—- —-

HOLLERITH:

Why, in 1970, did a bunch of twenty somethings turn the basement of a Greenwich Village townhouse into a bomb factory? Let’s go back to the late sixties.

Music in: Bad Moon Rising, Creedence Clearwater Revival

JOHN FOGERTY (singer):

I see the bad moon a-rising

I see trouble on the way

HOLLERITH:

The rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival, released the song Bad Moon Rising. Its catchy kind of overused in movie soundtracks — not exactly a protest song. But listen to the lyrics. They’re pretty dark.

FOGERTY:

Hope you have got your things together

Hope you are quite prepared to die

Looks like we’re in for nasty weather

One eye is taken for en eye.

HOLLERITH:

And that mirrored a shifting political mood for a lot of people.

NEWSREEL:

The Draft Lottery, a live picking for tonight’s birth dates for the draft.

NEWSREEL:

Good evening the reverend Dr. Martin Luther King 39 years old and a Nobel Peace Prize winner. And the leader of the nonviolent civil rights movement in the United States was assassinated in Memphis tonight.

Music out

NEWSREEL:

Senator Kennedy has been shot. Oh My God, he has been shot

NEWSREEL:

“There have been some early demonstrations at this early hour in downtown Chicago’s Grant park. He heard a moment ago tear gas has been used as the demonstrators try to form a line and march on the Ampitheatre”

HOLLERITH:

And by 1969, half a million people marched on the U.S. Capitol.

ANTIWAR PROTEST SPEECH:

You can End the War!

(SPEECH FADE)

HOLLERITH:

Race, freedom of expression, poverty, and of course, the Vietnam war. It’s what people were talking about. It’s what they worried about. But the majority of the AntiWar movement was carried by young people.

On college campuses, the protest movement for social change had been building since the beginning of the sixties.

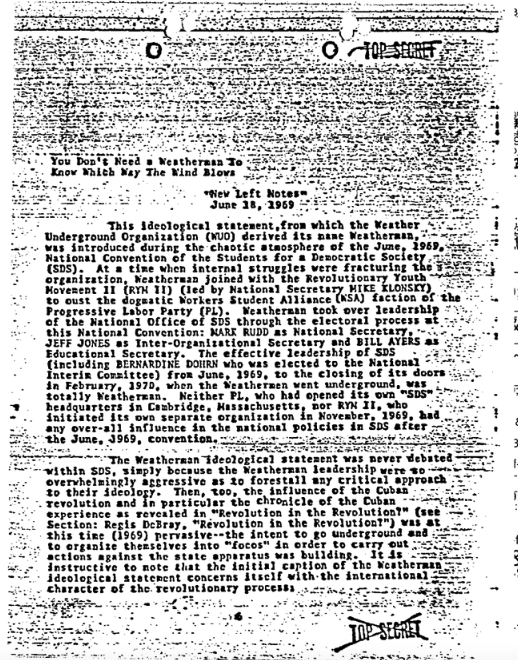

One organization, Students For A Democratic Society or SDS, held majority sway. By the late sixties, SDS membership ran up to tens of thousands of students. Even 100,000 by some estimates, making SDS, arguably, one of the most influential student political groups ever.

TODD GITLIN

I joined sds because I appreciated the people in it. Because they were both morally serious and strategically minded.

HOLLERITH:

That’s Todd Gitlin. Today, he’s a sociologist, professor and author of several books including The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. In his early twenties, Gitlin gravitated toward SDS. From 1963 to 64, he served as SDS president.

GITLIN:

One of the slogans that … they promoted and tried to embody was that the issues are interrelated. The issues meaning nuclear policy, military policy, civil rights, corruption of the universities, lack of democracy in general, and so on.

HOLLERITH:

Gitlin remembers feeling a kind of energy exuded by its members.

GITLIN:

And also because it was quite possible to feel in 1963 64 that the civil rights movement was on its way to winning.

HOLLERITH:

By 1965 US bombing campaigns in Vietnam had accelerated. And so the SDS organized what turned out to be the first national AntiWar demonstration in Washington.

Music in – Tendon by The Depot

GITLIN:

The war was, was so loathsome, and so incomprehensible, so sickening. That it, it heightened our sense of desperation… [13:20] So the revolt became more intense, more insistent, more militant.

HOLLERITH:

And the sds would never be the same again

Music out

HOLLERITH:

In the late 60’s, the SDS would become a far more militant group.

By then Gitlin had left the leadership. inside SDS, tension mounted between old and new ideas about how to end the war.

First there was the Progressive Labor faction. They believed the key was building support among America’s working class.

GITLIN:

—which had been a split off from the Communist Party earlier.

HOLLERITH:

Another faction, the Revolutionary Youth movement, was in favor of aggressive tactics.

GITLIN:

It took inspiration from an idea that there was a global uprising on the part of the poor countries, the countries of third world the most exploited countries, and that somehow SDS played a part in as an ally, to black organizers in the US.

HOLLERITH:

At an SDS conference in Chicago, June 1969, the conflict ignited into an outright split.

NEWSREEL:

The SDS entered its 7th annual convention yesterday in Chicago and accomplished little beyond a deep and bitter split between two factions. The so-called regulars and the Progressive labor group which follows the teachings of chairman Mao.

HOLLERITH:

The news media — even the FBI and their network of informants — pegged the Revolutionary Youth movement these so called regulars, as less organized and so not as threatening

That turned out to be completely wrong.

On the 5th day of the convention, one hundred or so Members of the Revolutionary Youth Movement stormed out of the building.

—- —-

HOLLERITH:

They would organize around a new manifesto

Music Start: Subterranean Homesick Blues, Bob Dylan

Eventually They would take their name from the lyrics of the Bob Dylan song, Subterranean Homesick Blues.

DYLAN:

Don’t Need A Weatherman To Know Wich Way The Wind Blows…

Music out

BILL AYERS:

We will build a revolutionary youth movement capable of actively engaging in a war against the imperialists.

HOLLERITH:

That’s Bill Ayers. He would eventually, take a leading role in the weathermen.

AYERS:

This fall in Chicago we will lead massive demonstrations in support of the Black Panther party

HOLLERITH:

Ayers is talking about The Days Of Rage. A mass demonstration that started with them bombing a police statue in October 1969.

NEWSREEL:

Findings claim that militant groups and counter demonstrators were planning street battles. He said the radical weatherman group intended to sack the downtown business area.

HOLLERITH:

The Days of Rage came out of a new protest strategy to bring the Vietnam War home by fighting in the streets.

In the midst of all the chaos, the Black Panther leader, Fred Hampton, distanced his party from SDS and the weathermen. Here he is in 1969 giving an interview to ABC News during the Days of Rage.

FRED HAMPTON:

We stand wayback from SDS and weathermen. We think its anarchistic, opportunistic, individualistic, chauvinistic, custeristic. And that’s the bad part about it. Its leaders take its people into a mass action where they can be massacred and they call that a revolution. It’s nothing but child’s play, it’s folly and it’s criminal because people can be hurt.

HOLLERITH:

By December of that year, Fred Hampton was shot during a police raid. And the weathermen, scattered into small collectives scattered around the country.

Music in – Tendon

By February 1970 the weathermen had shrunk to about 100 members. They’d given up marches for guerrilla operations

Music out

And some of those operations were being planned in Arthur Levin’s neighbor’s basement.

ARTHUR LEVIN:

One day, I was out walking the dog and there were people schlepping boxes into the house, but I didn’t know who they were.

HOLLERITH:

Arthur is the guy whose lived in the same house in Greenwich village since the 60s. He’s 87 now. But at the time, he wasn’t really worried about seeing strangers going into the house.

ARTHUR:

—because again the Wilkerson’s traveled a lot.

HOLLERITH:

Among the people crashing at the Wilkerson’s house was Cathy Wilkerson, their daughter. Cathy wouldn’t respond to my requests for an interview. But, in 2007 she spoke to WYNC.

CATHY WILKERSON:

My parents were away on vacation. I had gotten a hold of the keys through a ruse.

HOLLERITH:

This was about a week later, a Friday, March 6.

WILKERSON:

My parents were coming back that evening so not only did we have to prepare for this action, but I wanted the house to be clean and have my parents never know that we had been there…. So I had just washed all the sheets we’d used and was ironing them.

HOLLERITH:

In the same moment, Arthur was leaving his house.

ARTHUR:

For an interview at this free medical clinic trailer and was on my basement floor level heading for the door.

Music in – Flaked Paint by The Depot

HOLLERITH:

How many houses away were you?

ARTHUR:

I was right next door.

HOLLERITH:

He rushed outside. Flames and smoke billowed from the Wilerson’s townhouse. He ran back inside and called the fire department.

But Cathy was still in number 18.

WILKERSON:

When it went off, the floor sank, the ironing board fell over and I was standing their trying to figure out what to do with this hot iron in my hand because there were no surfaces left. It was just dust and swirling material…”

HOLLERITH:

At the same time, Susan Blanchad was standing in her kitchen when the explosion happened. About 100 yards down the street.

SUSAN BLANCHAD:

I was in the kitchen cooking nothing special…

HOLLERITH:

Susan is s 92 now – she lives in UpState New York close to her son, Mark.

BLANCHAD:

The explosion made a terrific noise. And it scared me I mean, it sounded like it was a few feet away which, which it I was. And I ran out. The explosion was for the most part inside. I mean, it didn’t blast out.

I discovered two women coming out of the building. One was almost naked and very frightened. And I don’t think they were severely wounded or anything. They got out very quickly.

Music out

HOLLERITH:

Susan says she didn’t know either woman. Their faces were black with soot. One of them, also named Kathy, had been showering when the explosion happened. She ran out of the townhouse with a towel wrapped around her.

Susan took the women back to her townhouse and gave them fresh clothes to wear.

BLANCHAD:

They seemed nervous. Very nervous. They didn’t tell me anything. I mean, they didn’t reveal anything. There wasn’t time for conversation or much of anything .

HOLLERITH:

Then she headed back out into the street to check on the fire. When she returned the women were gone.

Susan never saw the women again but not long after that day, she got a call from the FBI. They pressed her about whether she knew either of the women.

BLANCHAD:

And they asked me if I was a communist. And I said no, I owned a house, so it would hardly be likely that I was a communist… It was nothing except neighbors helping neighbors but they wanted to make it into some crazy thing.

HOLLERITH:

A few days later, new information came out about the explosion.

NEWSREEL OF THE TOWNHOUSE EXPLOSION:

Series of explosions leveled this townhouse five days ago. The body of Theodore Gold was pulled from the wreckage. Gold was a member of the weathermen, a radical faction of the SDS. Investigators first thought the explosion was caused by leaking gas but as their search continued they began finding evidence of explosives. Yesterday a second body was found, this one an unidentified woman. Then firemen uncovered 66 sticks of dynamite some of them stuffed in led pipes. Officials now believe the house was used as a make-shift bomb factory.

HOLLERITH:

Three people died in the explosion: Ted Gold, Terry Robbins and Diana Oughton. Cathy Wilkerson and her friend, Kathy Boudin, survived. Officials later found more unexploded dynamite in the ruins of the townhouse – enough to have leveled the entire street.

The group had planned to set off nail bombs at an officer’s dance in Fort Dix, New Jersey and the Low Memorial Library at Columbia University. That’s just around the corner from the Columbia Journalism school, where I am, now.

Music in – Tendon

HOLLERITH:

Where were you on this day in 1970?

MARK RUDD:

I was in New York, I was at a different grouping. Not that far away.

HOLLERITH:

That’s Mark Rudd – He was in the Weathermen on March 6, of 1970. The day the bomb exploded.

RUDD:

I didn’t know about it until quite late that night, when I came back to my collective and they said, Did you, Did you hear what happened? And then I went out, and I tried to find the survivors, so to speak. Yeah, sort of group. we group them, and I did.

HOLLERITH:

You found Kathy Wilkerson and Kathy Boudin?

RUDD:

I found everybody.

HOLLERITH:

Were they alright?

RUDD:

(deep sigh)… I think we were all suffering from a kind of.. a battle. I can only speak for myself. But we were, we felt like we were in the middle of a battle and we had to survive… Yeah.

HOLLERITH:

In her memoir, Cathy Wilkerson says she and Kathy Boudin met two other Weather members in a small NYC park the next day. They each debriefed what happened and were sent in two different directions. They dyed their hair and changed their appearances. Their faces were after all stamped in newspapers and wanted posters in the coming months.

The Weathermen kept going. They went into strict hiding. And renamed the group, the Weather Underground. A few months after the explosion, the group issued this so-called declaration of the state of war….

WEATHER UNDERGROUND COMMUNIQUE #1:

HOLLERITH:

In 1975 alone, the group took credit for 25 bombings but from 1970 to 75 are suspected of 45 total according to the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database.

NEWSREEL

The FBI says the weather underground which took credit for the bombing is the same underground group responsible for the bombing of the capitol in 1971 and the pentagon in 1972

HOLLERITH:

There were 11 other bombings in New York City. Plus one molotov cocktail thrown on a judge’s front lawn during a trial against a Black Panther member.

Besides the townhouse explosion, none of their other bombings killed or injured anyone.

Mark has since denounced the Weather Underground’s strategy for using violence. Back then, he remembers it like war.

RUDD:

So we saw ourselves as soldiers… We were gung ho, … to -. We were going to bring the war home.

HOLLERITH:

A decade after the explosion, Cathy Wilkerson turned herself in. She served 11 months in prison then became a high school math teacher.

“We had been a bright slight burning ourselves out in our own intensity,” Wilkerson wrote. “We had become a voice of outrage whose single mindedness had cut us off from the movement. We had created a bubble of our own reality and the bubble had burst.

The other Kathy – Kathy Boudin – arrested in 1981 in New Jersey. She acted as a getaway driver in the robbery of an armored car that ended with two cops killed. She served 23 years in prison where she composed poetry and wrote about parenting, feminism and women in the criminal justice system. Today, she is an adjunct professor in Columbia University’s school of social work.

She didn’t want to talk to me – but she did respond to my emails… I appreciate your idea about making the podcast. She wrote, I think it is a good idea. But I have not participated in recorded sessions about those eras and moments of history.

Sounds of New York City Subway pulling into 14th Street

Conductor… 14th Street transfer…

ANNIE AUSTIN:

I think this is us.

HOLLERITH:

When you go to Greenwich Village for the first time, it’s a prerequisite that at some point you get turned around.

Street sounds in Greenwich Village

HOLLERITH:

Is this 7th Avenue?

AUSTIN:

We’re going to what, 11th Street?

Okay, where are we, hang on.

HOLLERITH:

The streets wind and criss-cross. There is no 2nd, 5th, 6th or 7th Street.

AUSTIN:

Oh, lord.

HOLLERITH:

There’s a numbered grid – but it follows its own rules. Nothing like the rest of the city.

In the 19th century, before the neighborhood became an epicenter for art and culture, it was a rural village. When city planners tried to organize Manhattan into a geometric block by block street structure, Village Residents refused.

Of course, that would not be their last act of rebellion.

11th West, the street where Arthur still lives, where the townhouse blew up, is actually pretty nice today. Also, someone put signs on all the doorknobs.

HOLLERITH:

tax the rich. Do you see that?

AUSTIN:

Oh, here we are. Isn’t this it?

HOLLERITH:

Oh, yeah. That’s it.

HOLLERITH:

After the Wilkerson’s sold what was left of the townhouse, the new owners decided to add a few architectural changes.

Music in – Shoe Leather theme – ‘Squeegees’

HOLLERITH:

That Saturday in March when my girlfriend Annie and I were there, the townhouse was for sale for $19 million dollars. Since then, it’s been taken off the market. Trulia, an online real estate marketplace now estimates its value at $10 million dollars. Oh how times have changed during the pandemic.

But in some ways, they haven’t? I’m thinking about what Cathy Wilkerson wrote. “We had created a bubble of our own reality and the bubble burst.”

How many bubbles have formed in the last year since the pandemic started and how will they pop?

Music out

© David Hollerith 2021. To contact the author of this podcast, please reach out by email dsh2158@columbia.edu.