On a hot summer night in 1991, seven-year-old cousins Gavin and Angela were getting ready to play. Gavin was undoing his bike chain while Angela eagerly stood nearby.

Only a few moments separated them from Yosef Lifsh’s car and what would soon become one of the worst periods of unrest New York City has ever seen.

In this episode, we go back to that fateful accident that sparked what many know as the Crown Heights Riots. Over the next three days, this Brooklyn neighborhood fell into chaos with residents, police and community leaders clashing.

In looking back at what happened on August 19th, 1991, we explore Crown Heights itself, a neighborhood with many cultures and communities living side by side and ask: why did this happen and how did it get so bad?

Transcript

SADIA RAFIQUDDIN: So take me back to the moment you fell in love with Crown Heights.

FEVEN MERID: Um I don’t know if it was any moment in particular but I just felt like it was a really unique pocket of New York.

Music in

It has a very cool history in that it was home to one of the first free independent black settlements in the country…it has a vibrant Carribean community, it has the Hasidic community that came after World War II and you kind of see that all combined.

RAFIQUDDIN: What about it made you feel like you were home?

MERID: Where sometimes Manhattan can feel like one giant open mall, Crown Heights just felt like a place to live.

RAFIQUDDIN: I remember when we went together, one of the things that I noticed was the sky because there were no buildings around.

MERID: Yeah, so it was totally a place that I enjoyed living. And it’s why I was so surprised to learn about the riots…

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE: Second night in a row, the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn is in chaos.

MERID:…almost 30 years ago.

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE: And dozens of people have been arrested. And there is no peace in sight.

MERID: During the same month that I moved to the neighborhood. And it was such a big deal in New York. And especially in this neighborhood.

MERID: I wanted to know how this seemingly peaceful community that I was now experiencing was once the epicenter of what to some, seemed like a war zone.

It turns out…it all started with a car accident.

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE: The latest flare up followed a fatal accident last night.

MERID: And a split second decision in the moments that followed…

NONA CAPACE: Finally I had to curse at them, “I said get the fuck out of here!”

MERID: That would trigger a series of events. That within hours spiralled out of control.

Music out

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE: That left 7-year-old Gavin Cato dead.

Shoe Leather Theme Music in

MERID: I’m Feven Merid.

RAFIQUDDIN: And I’m Sadia Rafiquddin.

RAFIQUDDIN: And this is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today. This is season 1, New York in the 90s.

The Accident

Shoe Leather Theme Music out

SOUND: Jewish Brooklyn Tour Tape

MERID: Yeah I think this is Kingston? I mean, he said it would be like 40. A group of 40 students.

SOUND: Train door opening sound

SOUND: Rafiquddin talking in the background with the tour group.

RAFIQUDDIN: (to the tour chaperone) Yeah. Are you with these guys?

CHAPERONE: Yeah from Alaska.

RAFIQUDDIN: From Alaska? Welcome to New York. So I think we’re actually joining the tour that you’re about to head on.

CHAPERONE: Oh, really?

MERID: So this was in fact the group of high school ballroom students we would be going on the Jewish Brooklyn tour. The tour takes people into the heart of the Hasidic community in Crown Heights. You can see their synagogue, their shops and private homes. It’s really immersive.

And that’s why these students came all the way from Alaska to visit New York. To do some of this “cultural education.”

STEPHANIE: We should go on a Jewish tour. And we’re like, “yeah, let’s do it!!”

MERID: That’s Stephanie, one of the field trip chaperones.

STEPHANIE: So we’re just trying to learn about all the different cultures. So to expose the kids to the bigger world.

SOUND: Students waiting to start the tour on the sidewalk.

KATZ: Welcome to Hasidic Brooklyn, and I’ll be your guide for today. My name is Rabbi Yoni Katz and this is what I get to do every single day. I get to meet groups from all around the world. Recently as I told our friends here we had a group of Mormon students from Provo, Utah.

RAFIQUDDIN: Rabbi Katz has been doing these tours for a few years now and this one in particular is right before the Jewish holiday of Purim, which commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from being killed by Haman, an official in the Persian empire.

People dress up in costumes. We saw one person dressed up like a green clover. You can tell that Rabbi Katz loves doing these tours.

KATZ: You’ll see a lot of things, in the Hasidic world you’re sort of standing in the center of the universe here at Kingston and Eastern Parkway.

There’s so much history in this neighborhood, most of it good and some of it not so good like in 1991 there were the Crown Heights Riots here…

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE: TV Coverage

It’s all because of a traffic accident Monday night that turned Jews and blacks against each other. Bottles and rocks that kept police and residents running and ducking. Earlier tonight, protestors pulled a cab driver out of his cab and then set the car on fire.

ARI GOLDMAN: So I was a reporter for The New York Times for 20 years. And only one time in my career was I a war correspondent, and that was during Crown Heights.

MERID: Ari Goldman is a professor at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. In 1991, he was a religion reporter for the Times.

GOLDMAN: And I got a call from my editor on a Sunday night saying that there was a riot going on in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and there was one death.

Music in

MERID: Two cousins, Gavin and Angela Cato, were walking by President’s street, not too far from Gavin’s apartment. Angela and Gavin were close, like siblings. They were both seven years old and taking advantage of the last days of summer in Brooklyn.

It was just after 8 pm. But it wasn’t too dark yet.

Gavin was undoing his bike chain while Angela stood nearby.

ARCHIVAL TAPE OF GAVIN’S FATHER CARMEL CATO

CARMEL CATO: On that day August 19, I can remember clearly. I get outside where Gavin and his cousin Angela was playing. They were riding the bike.

RAFIQUDDIN: Gavin’s father, Carmel Cato, spoke to the New York Daily News about the accident back in 2011.

CATO: And I saw this car coming through. Within a split second, I say to myself, “Oh boy, this is gonna be an accident.”

RAFIQUDDIN: The car he saw was part of a motorcade.

Music out

GOLDMAN: The main Jewish group in Crown Heights, the Lubavitch sometimes called Chabad Hasidic group and their grand Rabbi would travel with a motorcade because he had a number of followers who would be with him especially when he made pilgrimages to his father’s grave and that night he had made a pilgrimage to the cemetery where his father was buried in Queens.

MERID: The grand Rebbe is the spiritual leader of the Lubavitch Hasidic community. His status to some Jews is not unlike the Pope’s among Catholics. So he sometimes had a police escort.

Music in

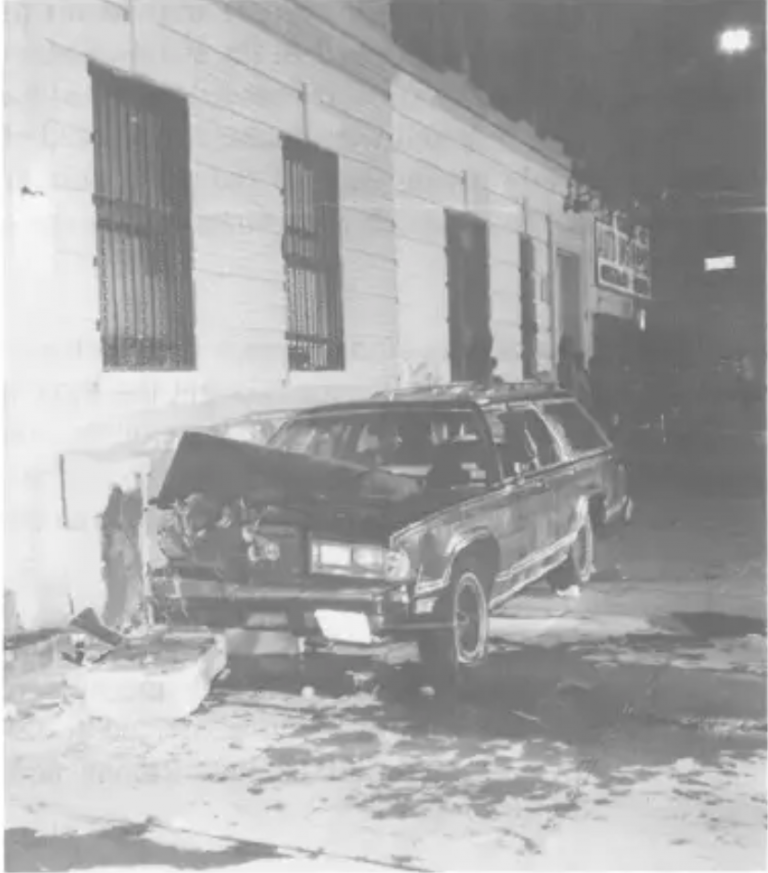

Twenty-two year old Yosef Lifsh had been chosen to drive one of the cars — a station wagon — in the motorcade. And it was a pretty big deal. On that day, the Rebbe’s motorcade also had an NYPD escort.

That evening, Lifsh fell slightly behind the Rebbe’s car. He didn’t want to lose him completely so he sped up to not get stuck at the light. Witnesses said Lifsh passed through a red light. His passengers said it was yellow.

Music out

It was then that Lifsh’s station wagon collided with another car in the intersection.

It spun out of control and ended up on the sidewalk where Gavin and Angela were standing. The station wagon struck them both — pinning them beneath the car.

SOUNDS: crowd from the riots

RAFIQUDDIN: A crowd grew around the scene almost immediately. Bystanders tried to free the two children, and so did Lifsh.

Within two minutes of the accident, two police officers and an ambulance were dispatched.

An emergency medical technician for Hatzolah – a voluntary Hasidic run ambulance service – also heard the dispatch.

He got in his car that was already loaded with emergency equipment and drove to the scene. He arrived moments before the city ambulance and began treating Angela.

By now, there were about 150 people at the scene. Lifsh and the people who’d been riding in the station wagon were being attacked by the crowd.

That’s when a police officer ordered Lifsh and his passengers into the Hatzolah ambulance.

Music in

In that moment, what witnesses saw and believed was that the Hatzolah ambulance tending to Lifsh and his passengers left behind the two black children, injured on the sidewalk.

Music out

MERID: Two more ambulances, a paramedic crew, and EMS captain arrived at the scene. They all began treating Gavin and Angela.

But the damage was done.

Meanwhile, at about 9 pm, the Police Department Accident Investigation Squad arrived at the scene and set up floodlights. Those are the big bright lights used in places like football stadiums. They only just ended up attracting more people to the scene.

By then, the rumor that the Hatzolah crew ignored the critically injured children and helped the occupants of the car was spreading. It was the story the news media went with that night.

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE

Witness on the street: The medical attention was not the same medical attention that the Jewish gentlemen got — you understand what I’m saying? They helped him before they helped the children and the children were the victims. Not him.

MERID: Ignited by this rumor, people took to the streets to vent their anger. Around 9:07pm, 911 callers began to report a riot.

GOLDMAN: Then there started to be chanting on the streets, “the Jews are killing us. They’re attacking us.” And it was chanting on the streets. And people began to walk through the streets in clusters and picking up sticks and rocks, assaulting people.

Music in

RAFIQUDDIN: But things were about to get worse. At around 11 that night, a 29-year-old Hasidic man named Yankel Rosenbaum was walking through the neighborhood.

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE

TV news reporter: After the accident violence broke out. Several blocks from the scene, a Hasidic man was brutally stabbed.

GOLDMAN: He was surrounded by a group of angry demonstrators, protesters, people that were chanting it was sort of out to do damage, and they surrounded him and stabbed him to death with a broken bottle. I should say they stabbed him with a broken bottle.

RAFIQUDDIN: Rosenbaum would make it to the hospital but later died from his wounds.

In the same hospital, Gavin Cato — the seven-year-old boy — also died that night.

There was no turning back now. The riots were in full swing.

SOUND: Riot crowd

MERID: The riots would go on for three days with then Mayor David Dinkins personally going into the neighborhood to help broker peace between the black and Hasidic communities.

ARCHIVAL NEWS

TV news reporter: The situation is still volatile and his appearance in Crown Heights didn’t seem to help.

MERID: And at the end of it all, it was reported there were almost 200 injuries, 27 destroyed vehicles including police cars, 225 cases of robbery and burglary committed and 1 million dollars worth of property damage.

RAFIQUDDIN: Our tour guide, Rabbi Katz, was 14 at the time of the riots.

RAFIQUDDIN: What do you remember from that time?

KATZ: Well, it was chaos. I mean, I didn’t grow up here in Crown Heights, but we used to visit very often. I think we came to New York as a family. And I think we may have avoided Crown Heights at that point, because, you know, this place was on lockdown for three days so I remember following the news very closely.

RAFIQUDDIN: Katz says that there were several factors that contributed to the riots — it wasn’t just the accident.

KATZ: It was just a mess. And that’s what happens when you have two people living so closely together, but feel that they have nothing in common.

Music in

They feel like oh, it’s them, the Hasidic Jews, and it’s us. And it only was a matter of time before something happened. And that just exploded

Music out

RICHARD GREEN: I usually try not to ever refer to it as riots, I refer to it as the crises of 1991.

MERID: Richard Green has been a community organizer since the late 70s. He founded the Crown Heights Youth Collective and is a well known figure in the neighborhood. And he was there during the riots as everything was unraveling.

GREEN: And it was something that happened there because of lack of knowing each other, lack of having any kind of corroborations with the community people, young people, of course, in an orthodox community does not mix with the non orthodox young people.

MERID: Green was at his home in Crown Heights at the time of the accident when he got a call from then Mayor David Dinkins asking for help to bring the situation under control. Green knew from that call that this incident would be different.

We spoke to Green a second time on not the best phone line.

GREEN: I was at my center and I got a call from the mayor’s office asking me what was happening in Crown Heights. The fact that the mayor’s office called — we’ve had little incidents happen before — but the mayor’s office called. When they did and then I looked at the news and saw it on the news, just right away I knew it. This one I knew was something to it.

MERID: Green explained to us it was the conditions of the day that gave rise to what happened. It was summer and a youth employment program has just ended because its funding was cut.

GREEN: Of course children are out of school.

So there were so many young people out in the streets, the weather conditions, it was all the ingredients there for such an incident to happen. And it did.

MERID: I wanted to ask first about the neighborhood pre-unrest, if there was tension brewing between the different groups in the neighborhood.

GREEN: Yeah, yeah there was tensions like any other neighborhood, but nothing major where one group in the community would go against another group in the community. Just normal, personal, people.

Music in

RAFIQUDDIN: While it’s true that it was a nice summer night. And there were a lot of people out because of it. That wasn’t the whole story.

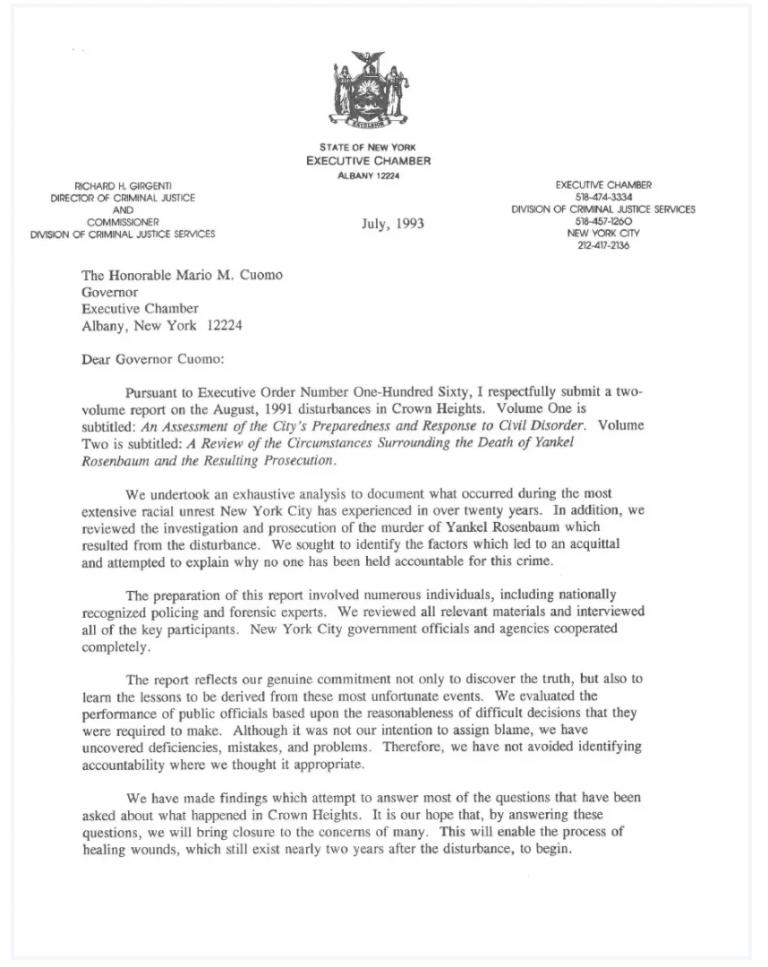

GOLDMAN: But there was a state investigation into what happened in Crown Heights, and there was a report that put a different spin on it.

MERID: Are you talking about the governor’s report?

GOLDMAN: Yes.

RICHARD GIRGENTI: Well we were asked to do a review because of a lot of questions that people in the community have been asking for the last two years that have remained unanswered.

Music out

RAFIQUDDIN: That was Richard Girgenti. He was the man behind a massive 500 plus page report on Crown Heights and the riots for then Governor Mario Cuomo. At the time Girgenti was the New York State Director of Criminal Justice.

The report has everything from police accounts, a day-by-day breakdown of the riots, and the history of both the black and Hasidic Jewish communities in Crown Heights.

And this history doesn’t exactly tell the story of a peacefully integrated community. Girgenti explained on The Charlie Rose show back in 1993.

GIRGENTI: There had been long-simmering tensions within the community, a community which is somewhat sharply divided between members of the Lubavitcher community and the black community such that when there was an accident involving a member of the Hasidic community who struck and killed a seven-year-old child who was on the sidewalk it raised to the fore tensions that had, I believe, long been simmering in Crown Heights.

RAFIQUDDIN: According to this report, there was tension, so much so that a whole section is dedicated to it. And to understand the community, you have to go back to the late 70s.

Music in

MERID: The report said that the black community believed a majority of housing resources dating back to the 70s went to the Lubavitch community.

Black home-owners who lived near the 770 synagogue which is the world headquarters of the Lubavitch movement felt like they were being pushed out of their neighborhood

Music out

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE FROM 1970s EXPLAINING BLOCKBUSTING:

TV news coverage: The bill submitted by delegates Paul Alpert and Richard Rhine bar the use of mass solicitation by mail, telephone or door-to-door to push properties onto the housing market. The tactics described in the bill are better known as blockbusting.

MERID: According to Girgenti’s report the black community, said quote, “that they are the targets of unsolicited, persistent and aggressive campaigns by Lubavitchers who offer to buy their homes for exorbitant sums.”

MERID: But according to the Lubavitchers, it wasn’t intended to be harassment. Crown Heights native Rabbi Simon Jacobson attempted to explain in a recording. This was from the Brooklyn Historical Society’s Voices of Crown Heights Project.

VOICES OF CROWN HEIGHTS PROJECT TAPE – RABBI SIMON JACOBSON: The Jews living in Crown Heights feel that they’re staying here because the Rebbe is here. And they feel the blacks are more, their being here is arbitrary, if they have a good deal they’ll sell.

Cause Crown Heights is not like their, there’s no Rebbe here, they’re just comfortable here.

It can seem to the person living here you know, like “I live here, this is my home.” People leaving notes on doors, “if you wanna sell your house call” and enough people do it, blacks began feeling like they’re being driven out which wasn’t the intention.

RAFIQUDDIN: The Lubavitchers wanted to remain close to the 770 synagogue because they were following the orders of The Rebbe. In 1969, he had urged them to stay in Crown Heights.

MERID: The black community of Crown Heights may not have a Rebbe as Rabbi Jacobson describes, but they do have their own distinct connection to the neighborhood.

MERID: You may recall, at the beginning of this episode, I mentioned Weeksville, one of the first free independent, black communities in America. Well that was created right in Crown Heights in the 1830s.

And like the Jewish Brooklyn tour, there is a Weeksville tour that takes you into the original homes of the settlement. We couldn’t take that tour because of the Global Pandemic…but here’s a recording of Weeksville Heritage Center’s former director Pamela Green discussing it’s origins.

ARCHIVAL TAPE – PAMELA GREEN: It was named for James Weeks and he bought property from an African American man who bought property from the Lefferds, a large established white family here in Brooklyn. And partly the reason for buying that property was to establish a community to get people to purchase real estate because in order to vote, you had to own property. So one of the things that made Weeksville a very unique community was that it had a large population of property owners.

MERID: So it was especially antagonizing for black homeowners to be constantly asked to put their homes up for sale.

In 1987, the New York City’s human rights commission looked into claims of blockbusting in Crown Heights. It found no evidence of that practice — but it did criticize Lubavitchers for increasing community tensions.

Music in

RAFIQUDDIN: These housing issues weren’t the only source of tension between the communities.

There was also the issue of the cops. And a deep seated belief that the black community was mistreated while the Hasidic community received preferential treatment.

Music out

MERID: In 1978, a prominent businessman and civic leader in the black community of Crown Heights died at the hands of two police officers. His name was Arthur Miller Junior.

VOICES OF CROWN HEIGHTS PROJECT TAPE – FLORENCE MILLER: He said something has happened. He said the police have him and put him in the back of the car and he doesn’t look right.

MERID: That’s his widow Florence, in another recording from Brooklyn Historical Society’s Voices of Crown Heights project.

MILLER: They said well it was an accident because the police panicked. And it was pushed under the rug as usual and they killed a black man.

MERID: Two days after Miller’s death, a black teen, was beaten into a coma by members of the Hasidic patrol which was quoted in the report as a vigilante group that harassed black men.

Following these incidents, nearly 2,000 people marched from Crown Heights to City Hall in protest. And no one was ever held accountable for Arthur Miller’s murder.

RAFIQUDDIN: Girgenti’s report gives so much context into the incredibly complex relationships in the neighborhood.

And the thing is, both groups have unique ties to Crown Heights. But these complexities were left out of most media coverage at the time.

Music in

And something else got missed….

There was another person on the ground witnessing it all, someone who was directly involved.

Music out

NONA CAPACE: I could have taken time off. We used to have concerts in the precinct area, free concerts. And I remember that night, BB King was going to be there. And I’ve seen him before. I love him. So I was going to go to that concert, take time off and go to the concert. Well, that most certainly didn’t happen.

MERID: In 1991, Nona Capace was a 40-year-old police officer at the 71st precinct in Crown Heights. She was on duty the day.

She was nearby on Utica Ave when she got the call. When she arrived at the scene, there was already a crowd.

CAPACE: And I had to help carry one of the men, one of the Jewish men to the ambulance.

MERID: That’s the jewish ambulance — Hatzolah. Lifsh and his passengers had also been injured in the crash.

CAPACE: They wanted to put a collar on him and everything because the head injuries and all. I said they were very bloody and they tried to say we’re going to stabilize and they couldn’t do that.

MERID: Capace had to work her way through the crowd, which by now, had become a mob.

CAPACE: They were rocking the car, they were throwing things I got hit in the hand with with a bat, some type of stick, I was hit in my shooting hand, my right hand and I helped carry them over to the ambulance and they were rocking the ambulance, you know the Jewish ambulance, the Hatzolah. So they were rocking it, they were throwing things.

MERID: At this moment, Capace made a decision.

CAPACE: And I told him I said you gotta get out of here. And he said, “but we have to treat him, we have to stay.” I said, “you have to get out of here. Look what they’re doing to you,” you know. It’s like finally, I had to curse at them, I said, “get the fuck out of here! Look at what they’re doing to you.” So they left, they had to leave. Well the crowd got even more mad because the Jews, they said, “oh they took care of them and left.” They didn’t take care of them. They had no chance to stabilize these men.

MERID: Capace says Gavin and Angela were already being tended to by city ambulance.

But what the crowd saw was two black children, laying on the sidewalk, while Lifsh and his passengers were driven away.

MERID: Do you think that anything could have been done to change that perception?

CAPACE: No. Not at all.

It wouldn’t have changed. It wouldn’t have changed. The ambulance was helping those kids. They had to be stabilized. They had to be stabilized, you know? Put them on stretchers. You just don’t pick someone up and throw them on the board.

You have to be very very careful with their neck everything, everything has to be stabilized to make sure and that’s what they did. They did 100% the right thing with those children.

The riot started with, you know, it wasn’t even because the ambulance left. This happened before, the minute the accident happened there was a big crowd going crazy…it had nothing to do with the ambulance. Nothing at all.

RAFIQUDDIN: Capace lives in Colorado now. She’s retired from the NYPD. After we talked to her, we couldn’t help but wonder if any news outlets had ever approached her before to ask her what happened that day.

So Feven called her back.

MERID: Investigators talked to you after the accident. But I was also curious if any news outlets ever approached you about the accident?

CAPACE: No, never.

MERID: Never?

CAPACE: Never. They only talked to the chiefs and the inspectors. They talked to all of the people that weren’t there when it happened. Cops on the scene, first cop, second cop…

RAFIQUDDIN: So how did Capace’s story get missed? Here’s Ari Goldman again, the journalism professor who covered the riots for the New York Times.

GOLDMAN: Yeah, I mean what comes to mind is that great quote about journalism is the first draft of history.

And when we’re trying to put together what we see on the street, what we understand to be an accident or a fire or, or an illness, right or a virus. We see it in the moment and we interpret it as best we can. In the limited time that we have. So we’re writing the first draft of history.

MERID: After Gavin and Angela were taken to the hospital. Capace returned to the 71st precinct.

CAPACE: I was there. My captain had asked, he says, “were you okay with what you did with the ambulance?”

I said, “Yes.”

Because they were getting, they were shaking the ambulance, they were throwing things, they couldn’t stabilize the guys, and it was just going to get worse.

I’m trying to hold onto my gun in my holster. Trying to hold back the crowd, trying to help them out, trying to save myself. You know, I ended up getting hit in the hand. You know, I said, “no I have absolutely no problem with what I did.”

Music in

I was on the verge of almost (pause) trying to explain to them how I felt when I saw this. Because it was an accident. It was a horrible accident.

Music out

RAFIQUDDIN: Gavin’s cousin Angela recovered from the accident but has never given an interview or spoken publicly.

On past anniversaries, Gavin’s father, Carmel Cato speaks about the loss of his son and the lasting impact of that day.

The driver of the Hatzolah ambulance, Chaim Blachman, still lives in Crown Heights. He declined to talk to us for this story.

And Yosef Lifsch, the young man who drove the station wagon, moved to Israel after the accident to get away from the attention.

Music in

MERID: But thirty years later, the neighborhood has been in the news again for recent anti-semitic attacks. In 2019, the New York Police Department reported a 67% increase in hate crimes for a total of 145 crimes. Of all of those crimes, 82 were anti-semitic.

And that issue of housing from the 70s, well, it’s still a problem.

The black community of Crown Heights is steadily shrinking. According to census data, Crown Heights lost 13% of its black population between 2000 and 2014.

Increasing rents and landlords looking to push out long-time residents by neglecting to improve living conditions are driving this change. In Crown Heights, the increase in housing prices was triple the city average at one point.

For people like Sadia and I who are new to the neighborhood or those kids from Alaska we met on the tour…it’s easy to miss that something profound happened here.

I look around and I see Crown Heights as a harmoniously diverse and happy neighborhood.

And it’s that too.

Music out

Credits:

Shoe Leather Theme music in

Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by me Feven Merid and me Sadia Rafiquddin.

Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Dale Maharidge is our co-professor. Keshav Pandya is our technical advisor.

Special thanks to Columbia Journalism Librarian Kristina Williams, Columbia Digital Librarian Michelle Wilson, Peter Leonard from Gimlet Media, Rachel Quester from The Daily, Emily Martinez and David Blum from Audible, Susan White from Garage Media, Madeleine Baran and Samara Freemark from American Public Media, In the Dark, Nate Di Meo from The Memory Palace, Jonathan Hirsch from Neon Hum Media, Clint Schaff from the LA Times Studios, and to Stuart Karle for his legal advice.

And another special thanks to the Brooklyn Historical Society’s Voices of Crown Heights Project whose work to preserve the history of the neighborhood helped us tremendously in this episode.

Shoe Leather’s theme music – ‘Squeegees’ – is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller.

Other Music by Blue Dot Sessions.

For more about this episode and Shoe Leather, go to our website www.shoeleather.org. To stay up to date on the latest Shoe Leather happenings, follow us on social media. We are on Facebook at facebook.com/ShoeLeatherCast and on Instagram and Twitter @ShoeLeatherCast.

© Feven Merid and Sadia Rafiquddin

Contact: fm2695@columbia.edu and sr3647@columbia.edu