In the 1970s, New York City was broke. Today, we know the city eventually bounced back, but at what cost? When a city is broke, who pays?

Mayor Ed Koch dramatically cut the city’s budget in an effort solve a $600 million deficit. Among the cuts, were city hospitals. One in particular, Sydenham Hospital in Harlem, was a neighborhood institution with an important history for the Black community. When Mayor Koch announced the city was closing Sydenham, the community mobilized to save it. The years-long fight culminated in a takeover of the hospital by demonstrators in September 1980. What made Harlem fight so hard for this hospital? And why wouldn’t Mayor Koch listen?

We spoke with New Yorkers who were central in the fight to save Sydenham. Ebun Adelona, MS, PhD, CPHQ, a community organizer whose dissertation “The Social Relations of Health” was a critical resource for this project. Carole Doneghy, a social worker at Harlem Hospital, and Judy Wessler, a health advocate, both of whom were active in organizing efforts. Haskell Ward, former Deputy Mayor in the Koch Administration, who resigned over the plans to close Sydenham.

Transcript

Roger Grimsby: Good evening I’m Roger Grimsby. Here now with the news. Harlem’s Sydenham Hospital is still occupied tonight by demonstrators. Neighbors who marched on the hospital nearly 24 hours ago to keep the city from shutting Sydenham down.

GRACE: It was 1980. A warm September evening in Harlem. Hundreds of protestors surrounded Sydenham Hospital, chanting and singing.

*DEMONSTRATORS CHANTING AND SIGNING “I’VE GOT FEELING”*

Unidentified demonstrator: …we have a good hospital here.

Sydenham hospital to give the care. So I want to say to you we are gonna be here all night. We’re gonna be here all day. This hospital belongs to the community. It does not belong to Mayor Koch. *CHEERS*

NYPD_F_0987 Manhattan Avenue and West 124th Street; Detail Sydenham Hospital, September 17-18, 1980. from NYC Municipal Archives on Vimeo.

DAN: It was a standoff. Mayor Koch vs Harlem. The mayor wanted to close Sydenham. And Harlem was fighting back.

Diane: We are holding this hospital, we’re gonna continue to hold it and we denounce the actions of the mayor, the unresponsiveness of the mayor and the bad faith of the health and hospitals corporation.

DAN: At one point, dozens of the demonstrators actually made their way in the front door. To save the hospital, they would take it over.

GRACE: This moment had been building for the better part of a decade. This was a final act of desperation. And it came as a surprise even to some organizers involved in the movement.

Ebun: I had no idea they were going to take over the hospital. I walked into the hospital and saw them there and I was like what is going on?

DAN: Ebun Adelona grew up in Harlem. She’d been fighting to save the hospital for over a year.

Ebun: I was stunned. I was like “you took over the hospital, you really took over the hospital? I can’t believe that.”

Still, she supported the takeover. Because she knew what Sydenham meant to Harlem.

Ebun: when we say we took over the hospital, I know it sounds like Well, did you take over the ER and you took over the *laughter* What did ya take over?

To take over the hospital didn’t mean interfering with doctors and nurses. Protestors occupied the administrator’s office — the guy who was in charge of Sydenham, and who answered to Mayor Koch.

Ebun: And everything continued to function without the administrator.

GRACE: They would stay for 11 days. Friends brought them food. They hung their laundry out the window.

And while the demonstration inside was peaceful, outside … things got violent. Judy Wessler was a public health activist at the time. She remembers one confrontation with the police.

Judy: They came out swinging. And what I remember is, you know Im white, so, so they didn’t try to touch me. But there was two cops beating up on a guy with their sticks on the ground and I wasn’t thinking. I went over there and said “stop hitting him” or something like that, and one of the guys sort of spun me around and said “lady get out of here before we start on you” you know or something to that effect. The violence of it really stuck in my mind.

NYPD_F_0989 from NYC Municipal Archives on Vimeo.

A few weeks later, the city closed Sydenham for good.

GRACE: We wanted to understand…what did Sydenham mean to Harlem…that made this community fight so hard to save it?

DAN: And despite all that…why did the city shut it down? I’m Dan Latu

Shoe Leather music

GRACE: And I’m Grace Benninghoff. This is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York City’s past – to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today.

DAN: This season, we’re focusing on the 1970s. We’ll look beyond the bell bottoms and disco to explore what made this decade notorious in New York’s his tory. A decade in which the Big Apple went by a far more sinister nickname — “Fear City.”

Newscast: Unionized employees of New York City who face dismissal have put out a booklet describing Fun city has fear city….

GRACE: In this episode we’re examining power. Who had it and who didn’t.

DAN: Because when New York City faced a budget crisis, someone had to pay.

Judy Wessler doesn’t throw anything away. At least that’s what she told us, and judging by her contribution to Columbia’s Health Sciences Library, it seems true.

GRACE Judy’s a public health activist who’s worked in New York City for decades. She donated dozens of boxes of notes, records, fliers; relics from throughout her career. Some of them date back to the 70s, when the fight for Sydenham first started. So Dan and I headed to Columbia’s medical campus to see what we could dig up.

Dan: Okay so we are here at the archives, we think

Grace: Yes, we’re walking in

Dan: Do we need to swipe this at all? I mean, nobody stopped me so we’re good

Grace: This place looks cool it’s like, all these other places

*creaking*

Dan: Oh my god this door

Grace: So creaky. All these other places we’ve walked in have been kinda more like hip new looking places, this definitely looks a little older, like more real books.

Dan: Like a collection of dictionaries

Grace: Yeah.

DAN: We wondered what these records from the 70s might be able to tell us about the impact the budget crisis had on the healthcare system.

Dan: I am so excited though we’ve just opened the first box

Grace: Yeah, we’ve opened the first box

Dan: Even just the titles look so… Harlem Hospital crisis folder

Grace: Sydenham. Wow we’re gonna have to come back here like 4 times

Dan: No, we’re gonna be here forever. I think we should start with this. Koch health folder

DAN: And after a few hours… we started to get an answer.

Grace: Wow, wow this is a cool map, check this out

Dan: What?

Grace: Hospital closings in low-income communities

Dan: Um, what?

GRACE: We found a map of New York City; it doesn’t have much detail, no street names or landmarks, but it’s big enough to pinpoint specific neighborhoods. There are about 15 dots on the map, each one represents a hospital that closed in the late 70s. Someone’s also taken a highlighter to it. There’s a key explaining that the highlighted areas are designated as low-income and medically underserved. All but three of the closed hospital dots are covered in highlighter.

DAN: We were shocked. We knew the city struggled financially in the 70s. But we didn’t realize the extent of how many hospitals were closed and in which communities. The map showed whole swaths of the city had lost access to health services. Most of them low-income neighborhoods. One of those dots on the map … was Sydenham hospital.

GRACE: Sydenham Hospital opened in 1892 out of a Harlem brownstone. At the time it was a private hospital. But After some financial troubles, the city took it over and the hospital moved to a 200-bed facility on 124th and St. Nicholas in the heart of Harlem.

DAN: Sydenham served predominantly the Black community of Harlem from the beginning. And in the 1940s, it took an even bigger step in serving that community. It became the first hospital in New York City to hire black doctors and administrators. It was also the first hospital in the nation to give black doctors admitting privileges.

GRACE: Admitting privileges are really important in Sydenham’s history.

DAN: So that’s when a doctor can get you into a hospital faster, right?

GRACE: Yes! but there’s more to it. It also means that the same doctor you see regularly is in charge of your care at the hospital. So before Sydenham, Black patients who suffered from cancer, or who underwent surgery, those with chronic health issues that routinely landed them in the hospital, they couldn’t count on having a doctor who looked like them overseeing their care.

DAN: Eventually this policy became citywide. But for Harlem, Sydenham being the first hospital to do this created a real sense of pride. Sydenham also had a reputation for hiring and promoting people of color. In 1971, Florence Gaynor became Executive Director, the first Black woman to head a major hospital in America.

GRACE: By the mid 70s, Sydenham was a trusted local hospital where people in the neighborhood went when they needed healthcare.

People like Ebun Adelona.

Ebun: This was an excellent hospital and it was a small hospital so it was very personal, and the care was personal.

She says that having Black healthcare providers gave her a greater level of trust in the care she was getting.

Ebun: I could trust my provider to do the best for me, and if you have any understanding and awareness of the history of healthcare in relation to people of color to be able to say, this is a hospital that I trust. I trust the providers in this hospital. I mean, that was the beauty of Sydenham.

GRACE: Here’s what you need to understand. There is a long and fraught history in the United States between Black communities and the healthcare system.

Ebun: if you know the history of African American people in relation to medical institutions, we have not had good experience in those institutions. One we’re looked upon as not having as much not feeling pain, so we’re under medicated for pain. The way you’re treated all of those things made us and make us reluctant to go into Eurocentric facilities.

GRACE: Nearly 21 years ago, a study out of Emory University found that Black Americans are systematically under-treated for pain compared to white Americans. Then, in 2016 a study by the National Academy of Science found that more than half of medical students and residents hold false beliefs around biological differences between Black and white patients.

DAN: In 2005, the National Academy of Medicine also reported that doctors are less likely to deliver effective treatment to people of color. Even after controlling for things like class and underlying conditions. One study showed that Black patients with heart disease received older and cheaper treatments than white patients.

GRACE: For Ebun, after Sydenham closed she didn’t feel she had many options left. Her experience isn’t uncommon. I sat down with Heather Butts, a public health professor at Columbia specializing in race, to chat more about this.

Heather : I would say that, you know, the relationship that African Americans have had with the United States has been challenging at best, torturous at worst. One can have a very meaningful relationship with someone who might have shared experiences, may look like you, and me able to relate to you culturally and ethnically and racially in a way that somebody else might not. Then that’s a win. And that’s positive. And that’s what African American healthcare workers can do for African American patients.

GRACE: She and I talked about what it meant for a Black community like Harlem to lose a hospital

Heather (12:58): When you remove a hospital system and people who have come to rely on it and had their children there and their grandchildren were born there and their great grandchildren were born there, that is removed from a neighborhood. So I think any neighborhood, you know, I don’t think African Americans have like the lion-share of like ‘oh we’re devastated when a hospital system is removed,’ But I would say if you come from a culture and a racial group where it has been difficult to create those kinds of bonds because of racism and prejudice and just getting access to quality care is challenging and difficult. When you find that and it’s gone, it becomes exquisitely difficult to find it somewhere else.

GRACE: Losing Sydenham would have left some Harlem residents with nowhere else to go, not necessarily because they couldn’t get to another hospital, but because they might not have felt safe getting care somewhere else.

Heather: If you’re African American where do you go after that in the 1970s and the 1960s? Um and the answer is.. Unclear you kinda take your chances. I think if you’re white there’s a little less concern in terms of what reception will I get at NYU, Roosevelt, St.Lukes, if you go there. You might have other concerns like physically getting there, travel, what happens in an emergency, but what you probably won’t be concerned about is ‘Will I actually be seen?’ ‘Will I get care?’ ‘Will I survive?’ And, as an African American you would have that concern.

GRACE: There was another hospital though, just a mile away from Sydenham. Harlem Hospital. People often pointed to it as a reason to close Sydenham. It was larger, had more modern facilities, and also staffed a number of black doctors and surgeons. A lot of people in Harlem already went to Harlem Hospital. Sydenham had 200 beds, while Harlem had 272. According to the 1975 community Health Survey, Harlem Hospital had nearly five times more visits per year than Sydenham. But Heather says taking all those patients from Sydenham would be a huge increase for Harlem Hospital, alot to absorb.

Heather: Where do you go? Harlem Hospital right? But um, can everybody go there? Does everybody go there? That’s a tall order. You know, how many people can one hospital necessarily absorb from another one is another question.

GRACE: From the dozens of people we spoke to, we got this sense that it was about more than just the number of hospital beds. Sydenham occupied a special place in Harlem. It’s specific history and legacy was important.

DAN: But the city was soon thrown into chaos and Sydenham would be collateral.

Anchor: New York City is right on the edge of financial disaster this morning

Anchor: Governor Hugh Carey of New York told Congress that default by New York City would be an economic Pearl Harbor for the rest of the country

Anchor: West German Chancellor Schmidt came here and said the collapse of the world’s financial capital could push the whole world back into recession

DAN: In 1975, New York City was suddenly bankrupt. It’s hard to pin down any one cause for the crisis. Experts say it may have been some combination of a global recession, outdated tax policies, and middle class New Yorkers leaving the city for the suburbs.

GRACE: Either way, there was a $600 million gap in the budget. The banks stopped lending to New York and Mayor Abraham Beame made drastic emergency cuts.

DAN: Bridges were suspended in air when operators were fired. Policemen were let go. Firemen were laid off. Even those with a job, weren’t sure they’d get paid.

Here’s a sanitation worker talking to BBC journalist Peter Taylor

JOURNALIST: How has the financial crisis affected your work?

SANITATION WORKER: My work? I lost all faith in the job. How can you work if you don’t know if you’re going to get paid on Friday. Two weeks ago they stopped the checks. They wouldn’t pay some of the men.

DAN: But it still wasn’t enough. So New York looked to the federal government for help. Mayor Beame went to Washington. He brought allies — mayors from other cities — to plead with Congress.

BEAME: The state has done all it can. The city has done and committed to do in the months ahead more of what we’ve done. And if the federal government does not help us, I think it would find the problem afterwards…much more serious

DAN: Here’s the Mayor of New Orleans

LANDEAU: New York is not here as a supplicant. It is not here for a handout. It is not asking for anything we haven’t done repeatedly for private enterprise or asking the federal government to do what it indeed has done for itself.

GRACE: The problem was the federal government didn’t trust New York to manage its own money. The city had gotten itself into this mess, so it would have to fight its way out.

Months of panic ensued. Would New York default on its debt? Who would save the city?

DAN: Speculation grew over whether President Gerald Ford would approve a bailout for New York. On October 29th, 1975, he made a speech at the National Press Club.

FORD: If we go on spending more than we have, providing more benefits and more services than we can pay for, then a day of reckoning will come to Washington. And the whole country, just as it has to New York City.

DAN: He was clear. If a bailout passed, he would veto. It would be too risky for the entire country to take on New York’s debt.

FORD: when that day of reckoning comes, “Who will bail out the United States of America?”

DAN: For the city, it was a terrifying realization. In their moment of need, there might not be anyone to save them. Alistair Cooke, a reporter for the BBC in New York, read the papers the day after Ford’s speech

COOKE: Five words blackened half the front page “Ford: let city go broke.” The New York Daily News was even better next morning ford tells city drop dead.

DAN: That last headline is so infamous that it actually inspired the title of this podcast. But neither of those sentiments were quite correct. Despite the headlines, the President never said drop dead. But that was the feeling in the city. What was most important for New York, is what happened next.

GRACE: First, Ford and Congress eventually did bail out the city.

FORD: I have decided to ask the Congress when it returns from recess a temporary line of credit

For $2 billion in aid, the city would have to keep a tight budget under the watchful eye of the state and federal governments. Under the deal, the city had to cut over $200 million from its budget for the next three years. This was Mayor Beame’s reaction.

BEAME: The coming months and years will mean new sacrifices for all New Yorkers

DAN: Second, came Ed Koch. He ran for mayor in 1977 — the first mayoral election since the financial crisis.

Koch: Bringing people together isn’t a matter of telling them what they want to hear, you can do it by telling them what they need to know.

DAN: Koch positioned himself as iron-fisted, ready to make the tough decisions.

Koch: The board of education wastes millions of dollars. The next mayor of New York must get control of the money spent on our school system. And he must set higher standards for our students and teachers.

GRACE: And it turned out to be a winning message. He was elected mayor with 50% of the vote

DAN: From day one, Koch put his agenda into action. He built a platform on saving New York from itself.

GRACE: One of the places Koch looked to save money was education. In 1979 he proposed massive cuts to the Board of Education, around 84 million dollars, 60% of the total budget cuts New York City made that year. But it was Harlem’s schools that would take some of the hardest hits.

DAN: Harlem lost more schools than any other neighborhood in Manhattan due to the financial crisis. Between 1974 and 1983 eight schools closed down in Harlem. In comparison, only one school on the Upper West Side closed during the same time.

GRACE: After schools, the city set its sights on hospitals.

DAN: The city had been trying to close municipal hospitals for a long time. The system had become incredibly expensive. I spoke with Dr. Merlin CHOW-KWAN-YUN, a historian at the Columbia’s School of Public Health about this.

Chowkwanyun: So this was always kind of a conversation, the 60s and 70s. But you can imagine, you can see why would accelerate at a time when the city’s finances are under strain. Right? Now, people are going okay, look, you know, we’ve kicked the can down the road. But we’ve really got to address this question of whether or not all of these hospitals necessarily need to exist in their current form.

DAN: A lot of municipal hospitals were saved by affiliating with a private hospital or academic medical center that could take on their costs. But Sydenham remained unaffiliated. Hospitals that didn’t affiliate usually had something in common

Chowkwanyun: An intense neighborhood localism that was suspicious of a big outsider coming in, to swallow a neighborhood, a neighborhood institution

DAN: Sydenham, unaffiliated, only had the resources laid out for them in the city budget. According to the mayor and his associates, Sydenham was outdated and underutilized compared to the nearby Harlem Hospital.

Chowkwanyun: He and other people in the department of hospitals have long seen it as this thing that, you know, was there but perhaps didn’t need to be there from a kind of cold rational utilization and cost perspective.

DAN: They said it was costing the city $9 million. And since there were bigger hospitals in the neighborhood, patients could find care elsewhere.

DAN: Dr. Chowkwanyun is clear about the expenses Sydenham was racking up, however he adds numbers don’t always account for everything.

Chowkwanyun: Sometimes the quantitative metrics don’t tell the whole story. So let’s say sydenham, you know, only they did have a utilization rate that was under norms that would classify it as an underused hospital and one that, you know, wasn’t quite cost effective. But, you know, is that really the right metric?… the mistake people make is, is getting into binary thinking, you know, you either have to run the hospital, the way it always has been run, or you have to shut it down completely. So I do think, the proper thing…is to kind of constantly rethink the form of, of, of healthcare delivery, and see if you can preserve some of these culturally important features,

GRACE: These are the things the city was considering when they made the decision to close Sydenham.

DAN: This is Haskell Ward. He was Deputy Mayor for Ed Koch and the highest ranking Black official in City Hall. He remembers the beginning of the administration.

Haskell: Ed had the attitude that he was going to show his bravado. And he was going to show that he would tackle very difficult issues…New York had been considered over the years difficult to govern… And that he was going to be a one who came in with the strength… to make some very difficult changes..

DAN: Haskell remembers one day thousands of protestors marched across Brooklyn Bridge to CIty Hall. They were rallying against police brutality under Koch.

Haskell: We put police on horseback, completely around City Hall. And in the midst of all of that, I’m sitting there. Ed and I were sitting there and Ed decides that he wants to go and have lunch across the street and walk through those protesters. And show that, you know, they weren’t going to stop them from doing what he wanted to do. And I said, Ed you’re nuts, you’re completely nuts. Why would you provoke that kind of thing? And he was given to that kind of attitude.

DAN: One target of the mayor’s focus was hospitals. The Mayor’s position was that New York could not continue taking losses from the public hospital system. The city estimated it was losing $55 million dollars. Other mayors had been afraid to touch hospitals because it was too controversial. That’s not how Koch handled things.

Haskell: When it came to the hospitals, I think that Ed had a had a position largely framed on highly charged political instincts on his part, that he had to show some kind of decisive action

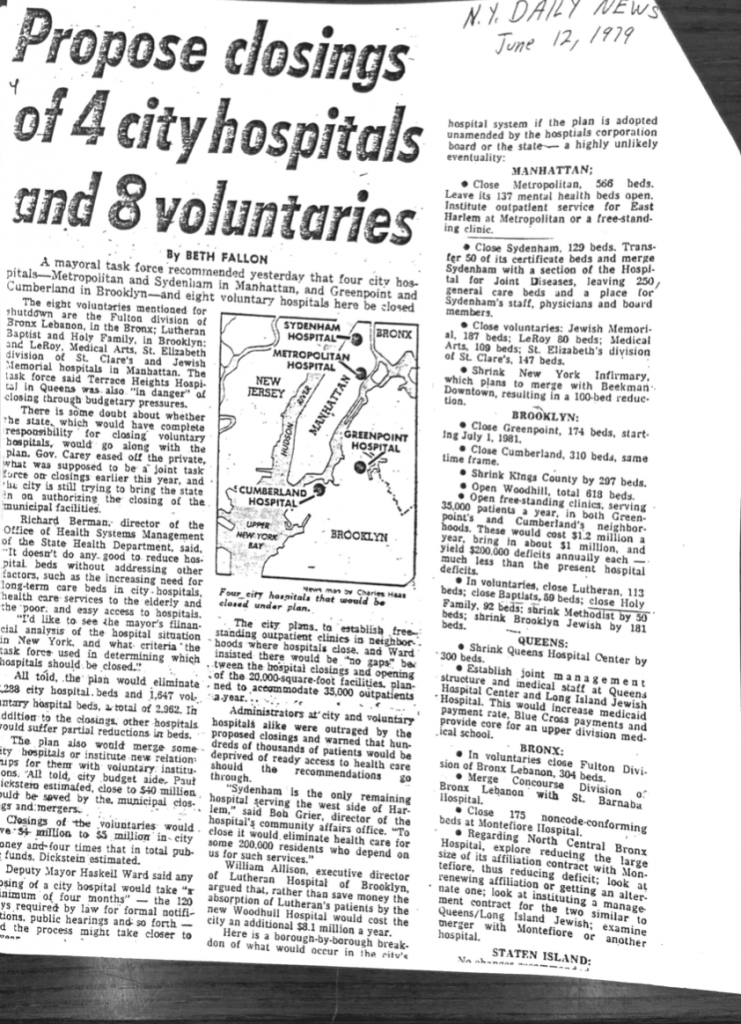

GRACE: On June 11, 1979, it was announced that the city would be closing four municipal hospitals. All four were in minority communities. Two in Brooklyn, and two in Harlem.

GRACE: Haskell Ward was the one who went out and publicly talked about the mayor’s plan. He had to tell the community why they were shutting down Sydenham.

GRACE: He says he didn’t always agree with the mayor,

Haskell: The reality was that we’re closing a facility and the optics of closing a facility in such a healthcare deprived area didn’t make sense politically or health wise.

GRACE: But, it was his job.

Haskell: I would not as a public official, as be out disagreeing with our stated policy.

DAN: Haskell was concerned about the Mayor’s decision. There were already plans to replace the hospitals slated to close in Brooklyn. But for the hospitals in Harlem there were no such plans. When Sydenham closed, no new hospital would be built in its place.

Haskell: but if you close it, and then there is no replacement, that is the issue. And that is what bothered me about the whole idea. You can’t just do that. And the fact that they were both, they were both facilities in black and brown neighborhoods. That was something that I couldn’t countenance.–

DAN: He says he brought this up to the mayor. But Koch wouldn’t listen

Haskell: He really was unresponsive, to the notion that changing them would have a disparate impact on black and brown communities

Haskell: I think he had a very strong political sense that there were things that you could do to show people that you were a decisive leader. And if it impacted blacks then so be it. I think that was where he was tone deaf

GRACE: Municipal hospitals also had a reputation for taking all patients. Even those who couldn’t pay.

Haskell: 33:01 There are people who need emergency circumstances where they can’t afford anything. Sydenham’s policy was to take everybody who had a lot of need for care.

DAN: Haskell says he tried to offer alternatives. One idea was a more effective system for collecting patient fees.

Haskell: My position in terms of the fiscal aspect was we need to devise a way in which we can collect monies due to the city and and spend more time creating a more effective collection system.

GRACE: But he says the timeline of this plan was too slow for the mayor. Koch felt the gap in the budget needed to be fixed immediately.

GRACE: According to Haskell there was another proposal to save the hospital. Potentially with help from the state and federal governments. But the state saving New York did not sit right with Koch.

Haskell: Ed was like any mayor of New York, they didn’t want the governor running the city.

DAN: For Koch and his advisors, Haskell was standing in the way of the city’s financial success. For those who opposed the closure, he wasn’t pushing Koch hard enough. He was a stand-in for the mayor at public meetings, and as a result faced backlash from the community. Protestors wrote songs about him, the New York Amsterdam News covered a meeting where he was booed and heckled by activists. Community leaders were openly critical of him.

Haskell: Didn’t bother me. that’s what you get when you’re in public life, and particularly in a city like New York

Haskell: But, you know, no, I was a member of his administration. And you don’t go out blasting the mayor

DAN: In fact the strength of the backlash made him feel more resolved that closing Sydenham would be the wrong call

Haskell: I had to listen to what people said. In fact, some of my views were influenced by the strength of some of the opposition that people had.

GRACE: Ultimately, Haskell made a decision. If the mayor was going to move forward with the closures, he would resign from his post.

Haskell: That’s what I said to the mayor. There isn’t any way for us to reconcile this. You were elected. And I wasn’t

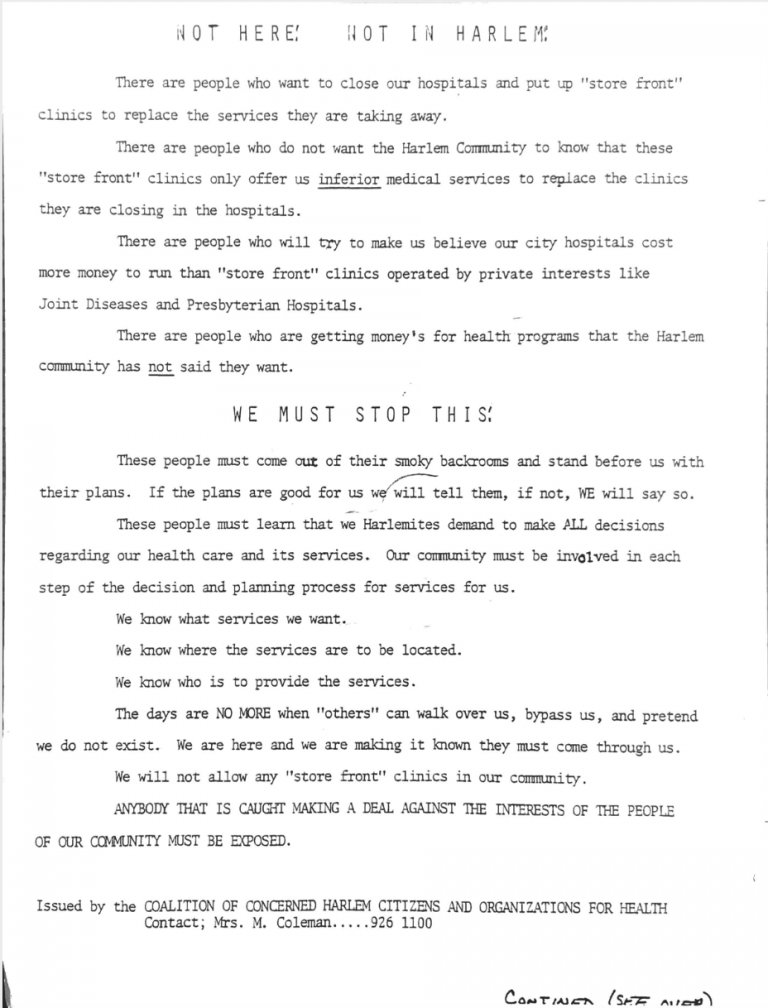

GRACE: By the time the city officially announced Sydenham’s closure in June of 1979, activists in Harlem had jumped into action. They didn’t have a roadmap for how to stop a hospital closure, so they tried pretty much everything.

DAN: Carole Doneghy was a social worker at nearby Harlem Hospital and active in organizing to save Sydenham. She led walks around Sydenham every night to protest the closure.

CAROLE: Monday through Friday, we would demonstrate. And that was during the dinner hour. So one season one fall season, it was on cold time, we were out there and other people would drop in and give maybe an hour to walk around and demonstrate and keeping the issue alive.

DAN: She says these demonstrations weren’t about being the biggest or loudest. It was about consistency. They were letting Koch know that they weren’t going anywhere.

Dan: And did you feel like there were moments where you felt you really were going to prevent the hospital from closing?

Carole: Yeah.

GRACE: Ebun handled policy. She conducted meticulous research and drafted proposals to keep the hospital open. At the time of the occupation she and other organizers had formed a corporation. She was proposing that Sydenham continue to operate privately under the Sydenham Hospital Corporation with funding from the federal government. Taking the financial burden off the city.

She went to the state with the proposal. And when it was rejected, she took a train down to Washington. She brought a plea directly to then President Carter’s administration requesting federal funding for Sydenham. She says she was feeling hopeful.

Ebun: Yeah I did feel that our proposal was going to get accepted, we really felt that way but then what happened was the HHS came up with a concept of the hospital serving the community of addicts.

GRACE: The Carter Administration said they would fund a drug and alcohol clinic to replace the hospital, but the community immediately rejected that idea.

Ebun: The responses that people gave was: they just think we’re addicts. We want a hospital and they’re offering a hospital for addicts and they think that’s what we are, and no we’re not going to accept that.

DAN: Judy Wessler used her experience as a public health advocate to pressure city hall and the hospital board.

She organized opposition and rallied groups for public meetings, trying to convince the city to keep Sydenham open.

Dan: What were your interactions like with the administration?

Judy: Mainly yelling at each other that I remember. We tried to sell the idea of getting additional funding, getting federal funding and they weren’t interested.

DAN: Judy had fought for other hospitals before, but she says there was something different about this fight

Judy: It was a broad community fight and there was an attachment to Sydenham that maybe wasn’t present in other hospitals.It was a very strong, very spirited fight.

GRACE: So that brings us back to that September evening. The occupation. All options were exhausted and the official closing date of October 1st was getting closer.

DAN: Leaders of the movement had a plan. Koch’s administrator at the hospital was ordered to begin shutting down services. If they could stop him, they could buy more time to find a solution. Something to keep the hospital open long term.

GRACE: Ebun wasn’t actually camped out inside, she was working on that policy proposal we mentioned earlier. Part of the reason for the occupation was to give her more time to push the proposal forward and hopefully, keep Sydenham open without the city’s funding.

Ebun: The only thing we were stopping was the administrator from carrying out the various procedures that one has to carry out in order to close the hospital and that gave us then time to deal with the proposal, negotiate, etc.

Grace: So this was a move to buy a little bit of time?

Ebun: Yes

DAN: As the occupation went on, things grew more and more tense between demonstrators and police, who had set up a perimeter around the hospital. Koch had publicly called the demonstrators a bunch of communists.

Ebun: When Koch made his announcement that the communists had taken over, and then he had to send in the police that gave the police permission to riot. Now, I used to go there at night, and just snoop around and listen to them talking; the police. And what they would talk about is who they were going to get when they got a chance.

GRACE: On a Saturday about halfway through the occupation, things got violent. Judy Wessler doesn’t remember exactly how it started. But the aggression from police sticks in her mind.

Judy: The police department had set up a very strong outer rim. And it depends on who you talk to as to whether it was the community that started to breach the police line or if it was the police that jumped over their Johnny Bars or whatever they called them.

GRACE: Ebun rushed to her congressman’s local office to see if he might be able to do something to stop the chaos.

Ebun: I went to Charlie Rangel’s office. And I said to him, the police are rioting and they are chasing people across 120/5 Street, would you please call the police commissioner and tell him to call his police.

GRACE: Eventually, things calmed down. Protestors dispersed and so did the police. Demonstrators remained inside Sydenham for a few more days. Ebun continued work on her proposal. Operations at the hospital continued.

DAN: The last few nights, Carole went to rallies outside the hospital. Occupiers would come and speak from the steps. She remembers the atmosphere in the crowd.

Carole: more hopeful but resigned, believing it could and should be opened. But recognizing that they were not powerful people nor there were decision makers to these kinds of things, and that their only strength was in their numbers and the supporters of the community.

DAN: After 11 days, the occupation of Sydenham ended. Police carried demonstrators out of the building. Over the next few weeks patients were discharged or transferred to other hospitals, and Sydenham closed its doors for good on November 21st, 1980.

Ebun: If you really understand a system, then you’re not surprised. But you still attempt to make changes and to use the knowledge, the ability, the skills, the power that you have to lighten the load, and to bring about a change.”

GRACE: After Sydenham closed, Ebun stopped going to hospitals all together. She had loved the care she got there and didn’t feel safe going to other hospitals in the city.

Grace: Did you feel afraid that you might not be able to get the kind of care that you needed at other hospitals? How did that feel?

Ebun: For me?

Grace: Yeah.

Ebun: I knew that I couldn’t get any healthcare at another hospital and so what I did was begin to deal with holistic health. I said to myself, you’re gonna have to take care of yourself baby, because there aren’t any hospitals that you wanna go to. And you’re gonna have to learn how to take care of your child and make sure that she grows up healthy.

GRACE: After its official closure activists fought for another year to re-open the hospital. But they never could. Even so, Ebun feels confident they accomplished something important in the years they spent fighting.

Ebun: I’m proud of how we came together as a community and supported one thing. And then when we lost that hospital, turned around and elected the mayor, another mayor, a black mayor, the first black mayor in New York City.”

DAN: In 1989, David Dinkins would defeat Ed Koch in the Democratic primary. And go on to be elected the first black mayor of New York.

One of his key aides, Bill Lynch, was part of the group who occupied Sydenham.

DAN: Years later, Ed Koch reflected back on his decision to close Sydenham. Here he is in a 2013 interview with Piers Morgan

Piers: What would be when you’re honest about everything and the documentary is very brutally honest about the past what has been your biggest failure

Ed: I’ll tell you the biggest fault if you will is when we closed Sydenham which was a hospital run by black doctors?

Piers: That was in Harlem wasn’t it?

Ed:I said ill close it because thats what the experts told me to do but what i didn’t realize was the psychological pain and attachment that black community had understandably because it was the first that admitted black doctors when other hospitals would not, i didn’t apprentice that i wanted to do it on the merits

DAN: Koch goes on to say that Governor Andrew Cuomo during his first administration considered closing some state hospitals. At an event with top advisors to the governor, Sydenham came up.

Ed: And they asked me if I had a question, I was in the audience. My question was do you think i did the right thing in closing Sydenham? Of course you did! And I’m saying to myself jerks! don’t you ever learn!

GRACE: Today, New York City finds itself in another economic crisis. After the fallout of COVID-19, the city faces a potential $4 billion shortfall in its budget for next year.

Once again, leaders will have to decide who will pay the price to dig the city out.

DAN: Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by me, Dan Latu

GRACE: and me Grace Beninghoff. Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Rachel Quester and Peter Leonard are our co-professors.

DAN: Special thanks to Columbia Journalism Librarian Kristina Williams

Columbia Digital Librarian Michelle Wilson

Michael Barbaro from The Daily,

civil rights attorney Ron Kuby,

Madeleine Baran and Samara Freemark from In the Dark

Emily Martinez and David Blum from Audible

Susan White from Garage Media,

Professor Dale Maharidge, Fevin Merid, Elize (Ma-noo-kee-an), Rachel Pilgrim, and Josh Lash. Additional sound mixing by Peter Leonard.

GRACE:Shoe Leather’s theme music – ‘Squeegees’ – is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes (zoo ne)

and Camille Miller, remixed by Peter Leonard.

DAN:Other Music by Blue dot sessions.

GRACE: To learn more about Shoe Leather and this episode go to our website shoeleather.org. To stay up to date on the latest Shoe Leather happenings, follow us on social media. We are on facebook at facebook.com/ShoeLeatherCast and on instagram and twitter @ShoeLeatherCast.