On September 10, 2001, New York City newspapers reported that a newborn baby girl was found alone on a rock in Central Park — with her umbilical cord and placenta still attached. They said the baby was abandoned. And the mother could potentially face charges for leaving her child unsafe in one of the biggest parks in the world.

Around the same time, New York had just enacted the Abandoned Infant Protection Act, which allowed a mother to legally and safely relinquish her child to a fire department, police department, hospital or church. People around the city wondered: Why wouldn’t the baby’s mom take advantage of the law, known as the Safe Haven law, and save herself the trouble?

“The Miracle Baby” is about the journey of two curious reporters searching for the baby born just before 9/11, also looking to find out what societal conditions would lead a mom to feel like abandonment was the only choice. They encounter a world of inaccurate reporting, a man who helps deliver babies for a living, and a now 20-year-old woman who may or may not know her origin story.

Transcript

Sagine Corrielus: Childbirth is wrenching. Crushing. Mothers say it’s a feeling so terrible that it steals your breath and leaves you unable to speak. Sometimes you can see the actual contractions. Pulling and tightening around your abdomen until the pain gives way to tunnel vision and you’re ready to push.

But for many, the end result makes it all worth it.

The baby.

And with the support of doctors, a midwife, a partner, or even a close friend in a safe environment, the pain can be endured.

But what if you have none of those things?

MUSIC

The safe environment, the doctors, the midwife, or anyone at all.

What if you were all alone?

And what if you didn’t want to have a baby at all?

Jaden Edison: Back in 2001, Bobby Cuza was a reporter with Newsday.

Bobby Cuza: I remember very little because you can imagine, back in those days, I was a general assignment reporter, which means I just covered whatever breaking news of the day was happening.

But Bobby thinks he remembers where he was when the call came in about a baby — he was working at police headquarters.

Bobby: We call it the shack. That’s where there are reporters who actually work right inside of police headquarters covering police stories.

It was September 9th. Bobby thinks the story originated with the NYPD.

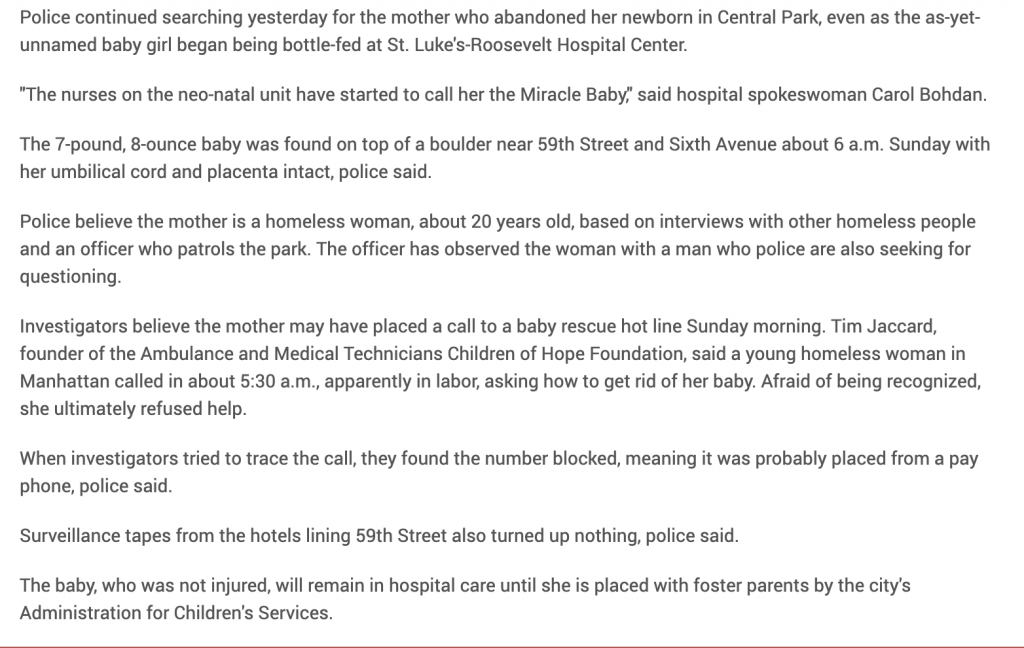

The headline read: Seeking Mom of Park Baby

A baby was found abandoned in Central Park.

She was a girl.

7 pounds.

Left on a rock, wrapped in a blanket.

So new to this world, her placenta was still attached.

MUSIC OUT

Rocco Parascandola: It appeared that the mom was aware, or at least wanted to not just leave the kid there and just completely forget about the kid. So that’s what made that one a little bit unusual.

That’s Rocco Parascandola, a reporter who worked on the story with Bobby.

An unhoused man found the baby at 6 am — just as the sun was coming up on a Monday morning.

Or so the story goes.

Bobby and Rocco wrote a 300-word story for Newsday that ran on September 10, 2001.

Newspapers across the country — including The New York Times and the New York Post — ran a similar story about the abandoned baby girl. They said nurses called her The Miracle Baby. But the next day, a different story filled the pages.

SOUND OF TOWERS

News Reporter: This is as close as we can get to the base of the World Trade Center. You can see the fireman assembled here, the police officers, the FBI agents. And you can see the two towers, a huge explosion now raining debris on all of us — we better get out of the way.

Bryant Gumbel: It’s 8:52 here in New York; I’m Bryant Gumbel. We understand that there has been a plane crash on the southern tip of Manhattan. You’re looking at the World Trade Center. We understand that a plane.

Sagine: That was more than 20 years ago — and after September 10th — most of the big papers dropped the story about The Miracle Baby.

Bobby: I mean, there’s no follow-up to any story that happened on September 9, or September 10. Because not only did 9/11 change the world, but in terms of journalism, I mean, I would venture to say that every single story in the paper was 9/11-related for weeks.

We wanted to know, whatever happened to that baby girl — where is she now?

MUSIC

I’m Sagine Corrielus

Jaden: And I’m Jaden Edison.

This is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast that digs up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today. This season we’re looking at stories from the day before 9/11.

Sagine: There was a lot going on on September 10th. It was fashion week in New York.

TAPE: Chanel spring summer 2001 collection.

Michael Jackson had just finished taping a TV special at Madison Square Garden.

TAPE: New York City. Michael Jackson.

And New York City mayoral candidates were gearing up for a primary election.

TAPE: This is the 2001 New York City mayoral primary democratic debate

And on that day there were about 350 babies born in New York City.

About half were girls.

And most mothers gave birth to their children in hospitals.

In this episode, our search for The Miracle Baby begins at Central Park and takes us all the way to a pub on Long Island.

Jaden: There are twists and turns. Ups and downs. And everything we thought we knew about journalism, adoption, and motherhood is completely turned on its head.

This is Shoeleather Season 3: The Day Before. You’re listening to The Miracle Baby.

MUSIC OUT

The Park

SOUNDS OF CENTRAL PARK

Sagine: Manhattan Island is divided by one of New York’s greatest wonders: Central Park.

And during the day it’s this gorgeous stretch of land with rounded boulders, tall trees and lakes.

Tourists and locals take long walks on trails and line up behind hotdog stands. The sounds of a bustling city start to blur with the sounds of nature

But at night, it’s always been a slightly different story. It’s seedier. Emptier. And even in a city that never sleeps — it can feel, well, dead.

Sagine: Central Park was kind of a dangerous place back then. I wouldn’t really be out here by myself at night, to be honest, even in this day and age.

In the early 2000s, the city was caught in that narrative — that Central Park was a dangerous place at night.

Stories of murder and robberies dominated the headlines. The park had gained a reputation. But things hadn’t started out that way.

MUSIC

Jaden: In the beginning, the western edge of the park was built on a Black community called Seneca Village. Seneca Village was acquired through eminent domain, which allows the government to take privately-owned land for public use, without compensation. And since 1857, Central Park has been a place for New Yorkers to get away from the hustle and bustle of city life.

But not in 2001, especially not for a newborn.

SOUNDS OF CENTRAL PARK

The Miracle Baby was found near the corner of 59th street and 6th avenue.

Midtown, one of the more bougie parts of the city, even back then.

Across the street are bright lights — restaurants, cafes, and the legendary Plaza Hotel. It’s one of the most expensive places to stay in New York.

MUSIC OUT

We think we’ve found the place where the baby was left.

Sagine: Just to give people a visual, like these rocks are just gigantic boulders. Not super tall, but like the very wide kind of steep, like very jagged edges.

Jaden: There were like these kids that walked past me. And this one little girl was like, ‘Hey mom, can we, can we go on top of the rock?’ And she was like, ‘No, it’s not safe up there.’

Sagine: This rush to keep your children out of harm’s way is common. So common in fact that psychologists describe it as mother’s instinct – maternal. That’s why when women do the opposite, they’re seen as cold, uncaring.

News Announcer: It’s difficult to watch. A teen mom drives up to the dumpster, in the back seat is her newborn stuffed in a trash bag. Then you see her coldly tossing the baby boy right into the dumpster like garbage.

That’s a story that made headlines nationwide earlier this year. In cases like this, the condemnation is swift. Brutal.

MUSIC

But there’s a context that we don’t get to see or hear about when these stories break. For starters, Abandoning a baby isn’t something that’s popped up in the last few decades. It’s been happening since humans started recording history. While 19th-century European women discarded their infants when they were starving and could no longer feed them, some African American slaves smothered their infants. They wanted to spare them from a life in chains.

But in this day and age, there’s a profile to a woman who does something like this — and she’s barely old enough to be a woman at all.

MUSIC OUT

Michelle Oberman: Infant abandonment outside of the hospital birth typically involves the folks who are giving birth for the first time and typically, relatively young. The modal age is around 19 and that’s an age that is skewed by the very rare cases that are way older, that you’ve got somebody who’s in her thirties. And if it wasn’t for that, I think we actually see even more, sort of teenage skew.

Jaden: That’s Michelle Oberman. She’s a professor of law at Santa Clara University and has written two books about why mothers abandon and sometimes kill their babies.

Michelle: The typical case is somebody who hasn’t made many plans at all. Right? So she hasn’t made a plan for having sex without risk of pregnancy. So they’re not necessarily looking to conceive, um, when they do become pregnant, they don’t really make a plan of any sort. And they tend to, because they’re young, to engage in what psychiatrists call, kind of magical thinking. Um, so maybe I’m pregnant. Maybe I’m not pregnant. Maybe the pregnancy test was wrong.

And because these young girls don’t realize it until it’s too late, they don’t really have a handle on what to do next.

Michelle: Having had no preparation for the labor and delivery, having just delivered a baby, the excruciating pain, the exhaustion of it. Right? All of that really defies the clarity of mind for, um, for executing a plan.

But more than that, these mothers don’t have the means to take care of the baby. Many of them are young, single, unhoused, or unemployed.

The Miracle Baby’s mother could have very well been one of those women. But in the early 2000s when she abandoned her daughter, there was a not-so-quiet movement being propelled by the media.

Anthony Michael Kreis: I think that there was kind of a — I don’t want to say a hysteria — but I think that there was kind of a hysteria about, um, you know, about infants just being left — just being left for dead.

That’s Anthony Michael Kreis. He’s an assistant professor of Law at Georgia State.

Anthony: And that might very well have influenced the angles and the perceptions that the media took at the time.

Sagine: News headlines started calling abandoned infants dumpster babies. In 2001, there were almost 800 news and magazine articles referencing this term.

Kreis says this fear of babies being dumped may have been slightly exaggerated.

Kreis: I don’t want to call it a trend, but you know, at least the media coverage, I think it might’ve been a trend.

MUSIC

In 1998 the U.S. Health Department conducted an informal survey of large newspapers across the country.

They found that 105 newborns had been abandoned in public places.

33 of them were found dead.

That same year 31,000 newborns were abandoned in hospitals — many of their mothers were struggling with addiction or living with HIV.

But back in the 90s and 2000s the government wasn’t officially keeping track of abandoned babies.

And for a long time, it was a crime to abandon your baby. Anywhere. Even at a hospital.

Kreis: And so there was just, a movement, I think, to find a way that mothers could relinquish their newborn babies in a way that was safe and that was consequence-free. You wanted to take away the stigma or the idea that there would be some kind of substantial consequences for leaving a newborn in a safe location.

Jaden: In 2000, New York State introduced the Safe Haven Law.

It allowed women who didn’t want to keep their babies to leave them in designated places or Safe Havens, no questions asked.

MUSIC OUT

Firefighter: Any firehouse. Or any hospital. And any police station …

AMBIENT NOISE

That’s a firefighter from Engine 23. A few blocks from where The Miracle Baby was found.

He’s explaining that any hospital, police or fire station is considered a Safe Haven.

Churches too.

Sagine: That fire station — it’s been here since 1906 — It’s less than a 10-minute walk from the boulder where The Miracle Baby was left.

It makes us wonder why didn’t the mother leave her baby there?

Jaden: We keep getting back to this question of like, if you have Safe Haven, why leave the baby in Central Park? And so one — there are a bunch of societal questions you could ask. I mean, even then, it’s like you have a pregnant woman walking around and it’s like, you’re asking a pregnant woman to walk to a Safe Haven?

But the biggest thing is that I think in 2001 Safe Haven was still relatively new, right? And we don’t know anything right now about, you know, the mother, you know, who left the baby in Central Park, but let’s say, this is a person who was perhaps experiencing homelessness, like, there are a lot of different like things going on at that point in time.

Sagine: I didn’t think about that.

There were plenty of things we didn’t think of. And it was impossible to put ourselves in this pregnant woman’s shoes.

But looking out at the New York skyline it’s easy to understand how someone might feel alone here.

MUSIC

As though they have no safe place to go.

And if you’re pregnant and in distress, it might be hard to truly understand what’s safe and what’s not.

MUSIC FADES OUT

The PSA

Tape: You have reached the New York state bandoned infant information hotline.

Sagine: In 2001 there were hotlines like this one.

Tape: For information on safe places to leave an infant under the Abandoned Infant Protection Act or to report an abandoned infant, press one.

The man who answered the phone described the law to me.

Representative: Let’s see, so you can leave a baby. Yes.

He explains that the baby doesn’t only need to be left in a safe place but they need to be left with a safe person as well. Like a firefighter, a police officer, a nurse, a doctor or a hospital official.

Representative: You can abandon a newborn baby up to 30 days of age. Okay. So it’s up to 30 days of age.

Back in the early aughts, after the law came into effect — there were posters and PSAs that ran on tv.

Cheesy sort of ones that are quintessential early 2000s ads.

MUSIC (FROM TAPE)

Tape: Honey, are you okay in there?

A mother checks in on her daughter. She’s distressed and in the bathroom. The daughter has a visible baby bump that her mother somehow doesn’t notice.

When the mother leaves for work, the teenage girl gives birth to the baby. She rushes out of the house and places the baby in a dumpster. But after a moment of thinking about it, she returns and deposits the baby in a Safe Haven box that has miraculously appeared just around the corner.

Hi. I’m Samantha Cole. If you just had an unwanted baby don’t panic. Under the new law, you can leave your baby at a Safe Haven within five days and not be prosecuted. A Safe Haven is any responsible adult who will call 911.

MUSIC OUT

Jaden: Back in 2001, the info about the Safe Haven law was out there. You just had to know where to look. The problem was that not everyone did. And not everyone could.

Laury Oaks: To me, a baby being abandoned is a distressing thing to hear about, to read about. But, at the same time, there’s so much more to the story.

That’s Laury Oaks, a professor of Feminist Studies at UC Santa Barbara.

Laury Oaks: So who is suffering in this? What happened to the person who gave birth? What were the circumstances around that in and of itself being unattended. What does it say about our society that our attention is drawn to the outcome, the baby and not about the birthing person who had to endure some kind of suffering?

Oaks worries that Safe Haven laws and society, in general, don’t work hard enough to understand what pregnant women are going through.

Laury: The Safe Haven laws are holding, to me, a high bar, because they’re saying, you can give birth alone, unsupported, and get yourself safely and the baby safely to a Safe Haven drop-off point.

Michelle Oberman, the professor from Santa Clara, agrees. And she answers an important question about why the miracle baby’s mother wouldn’t have brought her to a fire station.

Michelle: So even if they knew about the laws, they just delivered a baby by themselves. Right? And so all you need to do is talk to somebody who’s recently done this to understand how preposterous it is to imagine that you just — you hop off the toilet and you just, you know, grab that baby and get into the car and drop it off at the fire station.

But that was the Safe Haven messaging back then.

That a woman had options.

That the most important person in a situation like this was the child.

MUSIC

Sagine: As a side note, this same messaging is used today.

Most notably by Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett who brought up Safe Haven laws during oral arguments for a recent Mississippi abortion case.

But if we were to get into all that, we’d need another 45 minutes.

MUSIC OUT

Jaden: In the early 2000s, There were more PSAs. All urging the same thing: Give your baby to a safe place.

In an article Laury Oaks is quoted in, there’s one particular PSA that caught our eye. Laury described the video in great detail.

It’s a PSA about a little girl named Molly.

MUSIC (FROM TAPE)

TAPE: This is Molly. When she was born, her desperate mother knew that she couldn’t keep her. So she left Molly at a Safe Haven, with no questions asked.

MUSIC OUT

MUSIC

Sagine: A tan-skinned child appears — Molly. She has bluntly cut dark hair. She’s maybe 3 or 4 with apple-round cheeks and a wide toothy grin. She plays on a beach. A fair-skinned woman grabs her hand. The little girl seems to hold on tight.

On the screen, it says that Molly was born on a rock in Central Park. Just like our miracle baby.

MUSIC OUT

MUSIC (FROM TAPE)

TAPE: It’s safe, legal, and completely confidential. Safe Haven, a place that’s safe for mothers and safe for newborns.

MUSIC OUT

MUSIC

Something wasn’t adding up.

Molly and The Miracle Baby even had the same birthday.

But this baby was left at a Safe Haven — not abandoned as all the stories had said.

Either Molly was a different baby, or the New York Post, Newsday and The New York Times were wrong.

The video — Molly’s story — would lead us in the most unlikely direction.

MUSIC ENDS

We find Tim and everything changes

Jaden: Tim Jaccard founded the National Safe Haven Alliance.

The organization that produced that PSA about Molly — the baby born on a rock in Central Park.

Tim Jaccard: Everything now, I don’t do anything else other than Safe Haven. And deliver babies — I’ve delivered over 300 babies.

The alliance provides resources to Safe Havens across the country.

And back in the late 1990s, Tim was a police medic. In Nassau County, western Long Island.

His job was to respond to 911 calls and provide emergency care before someone was taken to the hospital.

While on the job, he came across 16 dead babies over 10 months.

Tim: I got a call, they gave me the call, 2350 of “Baby Not Breathing,” Mainstreet Courthouse, and I’m sitting in front of the door at the courthouse.

And I go in and I find a little baby boy, drowned in the toilet bowl with the placenta laying on top of the baby.

So I worked the child up, I intubated and did everything I could to try to save the baby’s life.

After coming across those dead babies in the 90s, Tim wanted to do something.

MUSIC

He says he went to state officials in New York to talk about this idea.

Sagine: Why not let women leave their unwanted babies in a safe place — without facing any kind of legal consequences?

Jaden: But according to Tim, they weren’t hearing it.

Tim: ‘You want the governor to sign a bill that would legally allow a woman to hand you a baby with no questions asked and walk away.’

I said, ‘Yes.’

He says, ‘You’re crazy. Nobody will ever sign a bill like that.’

Not long after, the state of Texas did.

Sagine: The governor was George W. Bush.

Tim: Texas became the first state in the United States to pass the bill stating that a woman can legally relinquish her child.

MUSIC OUT

Jaden: In 2000, New York did the same.

The governor at the time, George Pataki, signed the Safe Haven bill into law saying it would give “young, desperate mothers an opportunity to place their child in a safe place.”

A similar law now exists across all 50 states.

Tim also founded the Ambulance Medical Technician Children of Hope Foundation.

The foundation gives support to folks who want to “relinquish” their babies under the law.

And as long as the baby’s mother calls Tim to get help, it falls under Safe Haven.

The organization keeps the mom anonymous and uses its connections to find the baby a new family.

MUSIC

If the baby is found dead, Tim’s organization plans a funeral and a proper burial.

Sagine: We figured if anyone knew about Molly — this little girl in the PSA — it would be Tim.

And we weren’t wrong.

What Tim tells us next literally changes everything about what we thought we knew.

MUSIC OUT

Tim meets a woman

Jaden: After New York’s Safe Haven law passed in 2000, Tim started spreading the word about AMT Children of Hope.

That’s how he ended up at a Fordham University health fair in the Bronx, where he met a young Latina.

Tim: She says, um, ‘I have a friend that has a friend that is pregnant.’

I looked at her, and I knew she was talking about herself, and I said, ‘Well, you know what you can do? If you contact your friend, who knows the friend, who has the friend, that is the friend, that’s pregnant.’

And she laughed.

So we went through with that part of the story.

Tim gave the woman his information, and they parted ways.

Then before dawn on September 9, 2001 — Tim got a call.

MUSIC

He pulled the antenna up on his brick-sized cell phone and answered. Remember, it was back in 2001.

There were no iPhones.

The call was from Tim’s crisis center in Nassau County — a woman was on the phone and would only talk to him.

They put Tim on the call.

It was the woman from Fordham.

She called from a payphone.

She was going into labor, and she needed help.

Tim asked where she was.

She said, Central Park.

Tim headed over there.

Sagine: While she waited, the woman met a man who was also in the park.

Tim arrived — and before he knew it, he was helping deliver a baby.

On a rock.

An ambulance came and took the woman and her newborn to St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital.

Jaden: That was the last time you’ve seen the mom?

Tim: Oh, no, it was just before 9/11.

And I put Jane Doe Hope up in a hotel.

And then went to see her again just before 9/11.

And she disappeared and was gone, and I never saw her again.

MUSIC OUT

Jaden: The mom was gone, and Tim never found out what happened to her.

The baby survived and was later adopted.

Tim stayed in contact with the family.

He later took the little girl to California to film videos for the National Safe Haven Alliance.

Her name was Molly.

Molly in the PSA.

TAPE: This is Molly.

Tim isn’t just the dude who was partly responsible for Safe Haven laws across the country.

This is the man who delivered the baby we’ve been looking for this whole time.

Jaden: The initial reports indicated that the baby was left in Central Park, which I don’t believe was a Safe Haven at the time. So how did the relationship —

Tim: Yes, it was.

Jaden: Was it?

Tim: It was a Safe Haven.

Jaden: Very interesting.

Sagine: Here’s the thing:

Central Park isn’t actually considered a Safe Haven.

But because Molly’s mom called Tim, it fell under the law.

So how did the media get the story so wrong — Newsday, the New York Post, The New York Times.

Even a random paper in London.

Tim: How that happened was the birth mother was befriended by an old man that was drunk out of his mind.

He couldn’t even stand.

And we had an ambulance pick the baby up and brought the baby over to St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital.

And the baby was brought in and taken care of, but we couldn’t leave the old man there.

So we put him in the ambulance also, and he went to the hospital too.

And he got interviewed by a reporter.

Jaden: Part of what news organizations reported was that a man experiencing homelessness found the baby on a rock.

MUSIC

Tim thinks that happened because journalists interviewed someone who was drunk — a person who didn’t tell them what actually happened.

And so those stories just added to the narrative about baby abandonment being quote — “a perplexing and persistent phenomenon,” as The New York Times put it.

Stories that — until now — have survived without any correction.

MUSIC OUT

Safe Haven Party

Sagine: Two decades later, Tim’s foundation has expanded beyond answering calls in the middle of the night about babies being born on rocks. It’s Glitzier. Glammier. And it’s in Long Island.

TRAIN SOUNDS

Jaden: We’ve arrived in Wantagh, Wantagh, Wantagh.

It’s a brisk Sunday afternoon in the middle of winter in Wantagh. At Mulcahy’s Pub and Music Hall I’m greeted by a sea of white faces in biker jackets with bald eagles on them.

The room is packed — people are standing around two bars — drinks are free tonight.

On stage, a cover band plays everything from Whitney Houston to Queen. And lined up all along the stage are raffle prizes. There are jerseys and surfboards and gift baskets.

It’s a party-like atmosphere — one that doesn’t quite seem to fit the mission of the night. To raise money to help abandoned babies.

Jerry: Volunteer to help them. Any time Timmy calls, we’re to first up; we’re ready to go.

Jaden: That’s Jerry. He wears a biker jacket and is part of a motorcycle club called the Blue Knights. A bunch of them are here tonight, rocking shiny black leather jackets. It turns out —

They’re a group of retired cops that like to help Tim out when they can.

Jerry: So we escort the babies. We take them to the funeral home, to the church and then from the church to the cemetery. So we give them the dignity that they didn’t have in life.

Sagine: Tim kicks off the event with a speech about a half-hour after I get there.

BACKGROUND NOISE FROM EVENT

When we finally meet him in person, he isn’t what I expected at all. He reminds me of a kindly grandfather or your elderly next-door neighbor.

The kind of guy that gives even a stranger like me a kiss on the cheek when he greets me. He isn’t very tall and the only thing about him that lets you know he’s the man of the hour is his elegant red cummerbund. Everyone else is dressed a lot less formal.

But Tim isn’t the only person we’re here to meet tonight.

Someone else will be here too.

Another Safe Haven baby. Her name is Kaitlin, and she was also relinquished by her birth mom over 20 years ago.

She was adopted by Donna and Tom.

They’re middle-aged and happy to talk to us.

They explain how they first met Tim.

Donna: I had seen an article in the paper about a baby that was found. So I called Tim, and so I gave him my name and number and he called me four months later and said he had a beautiful baby girl for us.

In another bizarre twist in the story: Kaitlin was officially adopted on 9/11.

Tom: “She was born on the 5th, and in 2001 on 9/11, we were in the judge’s chambers in Mineola finalizing the adoption when the clerk came in and said ‘Your honor, the plane hit the second tower. They think it’s terrorism.’ And then the clerk came in and he said, ‘Stamp everything, make it official … boom. We’re closing everything up. Let’s go.‘

MUSIC

Donna: Having a kid through adoption has been even more rewarding than giving birth to my own. We tried for so many years, we tried in vitro, um, artificial insemination, surgeries. And to finally have this perfect child. It was just, it was a miracle.

Sagine: She’s like your miracle baby.

Donna: Yeah. Yeah.

Jaden: Donna and Tom are excited for us to meet Kaitlin.

And so are we.

We know she isn’t Molly. But she shares a similar story.

We wait hours to speak with Kaitlin.

But it turns out.

MUSIC OUT

She isn’t ready to share her story with us —

In fact, while we were there, she wouldn’t come out the bathroom.

Donna tells us that situations like this make her daughter anxious.

She apologizes.

The ethical dilemma

Jaden: Part of the intent of Safe Haven is to protect everyone’s privacy if they wish — so we knew very little when we started looking for Molly.

But we had some leads — a birthday, a first name, and a possible last name that had come up in our reporting.

We searched all the usual databases.

No hits.

But then I try something different.

MUSIC

I put in what we think is Molly’s last name and her birthday in the database.

I leave the first name blank. And then something pops up on my computer.

It’s literally one search result.

A woman born in September 2001.

She graduated high school in 2019 and lives somewhere in New York.

SOUNDS OF CHATTER

Molly.

My heart is beating out of my chest.

Sagine and I spent weeks trying to find this woman.

A girl born September 9, 2001 on a rock in New York City.

Sagine: No one thought we’d ever find her — not even our journalism professor.

Now all of a sudden she’s right here. Her address. Her relatives.

Except there’s one thing.

We hop on the phone to talk about it.

Jaden: You have a scenario where she might not even know, you know, her past and things like that.

You might have another scenario where she does know but, you know, is traumatized.

I’ve thought about the situation too with Kaitlin in the bathroom.

MUSIC OUT

You know I think just being more, I guess, patient and trying to really map out how we’re going to do it makes the most sense.

Sagine: No, I agree with you.

I’m also just thinking about the fact that Kaitlin didn’t want to talk.

Like this might be kind of tricky.

Tricky because we have no idea whether Molly knows her origin story — if she knows she’s adopted that is.

We don’t want to be the ones to tell her and risk traumatizing her. Or ruin her relationship with her family for the sake of our story.

Bruce Shapiro: Believe me, I am pulling this out of my ass as I talk to you.

It’s so complicated, okay?

Jaden: That’s Bruce Shapiro, a journalism ethics professor at Columbia University.

He’s the kind of teacher who would wear a dress shirt and tie with jeans and track shoes.

He’s also an expert on trauma reporting.

Bruce: I mean, first of all, just on the emotional part, or the intellectual part, there’s actually two things that Molly may or may not know. Right?

She may or may not know that she’s adopted.

That’s a first level.

And then she may or may not know the conditions of the adoption.

So in a way, it’s a slightly bigger question than just a, ‘Can we tell her about a Safe Haven thing?’

It’s actually a broader question about, what if we believe someone to be an adoptive child, and it’s relevant to the story.

Should we approach them about it?

Jaden: Another route could be potentially reaching out to mom first, right, which I think we have a pretty good idea of who the mom may be.

Her adoptive mom.

But a part of that, too, is how do we address that part of it?

Like there has to be like a really well-crafted message, you know, just to convey —

Bruce: Yeah.

And it’s complicated.

If Molly were a child, then it would clearly be — it’s the parent’s choice.

But Molly’s now an adult.

So you’ve got two adults who may have different perspectives on the same thing there, right?

And that’s, that’s complicated.

Sagine: One other option is Tim.

Bruce thinks if Tim has his own relationship with Molly, he might introduce us to her.

But that — like everything else — depends on what Molly knows.

We decide to go back to Tim.

Worst case scenario, he won’t tell us anything.

At best, he’ll introduce us to Molly.

Jaden: Through our reporting, we think we’ve been able to find Molly. But we’re having this dilemma, right?

Tim: Oh my God. Did you find her?

Jaden: We believe so. And so, here’s the thing —

Tim: Alright, be very, very careful with this.

Because I will take you into court if you intrude on her privacy.

Okay? I’m not joking.

This is something I’m very serious about.

Jaden: I’m a little caught off guard by this. Tim threatening to take us to court.

Sagine and I haven’t done anything illegal.

But we kinda get it — he’s concerned about Molly’s well-being.

Tim: Remember, I met her on a rock in Central Park.

She was there.

And she would have died.

I’m not kidding.

She would have died if the mother walked away.

She would not be here today.

I don’t want you to bring up that aspect of it.

Because, um, she knows that she’s here because of the Safe Haven program.

So Molly knows her birth story.

The real Molly

VOICEMAIL TONE

Jaden: Hi, how’s it going?

My name is Jaden Edison; I’m a journalism student at Columbia University.

I’m calling — I just, you know, wanted to see if you would be available to speak to me for a few minutes.

Jaden: That’s me.

Clearly nervous.

Leaving a voicemail after calling who we think is Molly.

Not long after, I finally speak to the woman we believe is the baby born in Central Park.

Jaden: If I’m not mistaken, your birthday is a couple of days before 9/11 — just based on just like publicly available stuff that I was able to find.

And so I was wondering if there was any sort of connection between maybe, you know, where you were born and like Safe Haven, or anything to that degree?

Woman: Um, no not that I know of — no.

After all that, it wasn’t Molly.

And if it was, she clearly didn’t want us to know.

Just to be sure, we went back searching.

MUSIC

We start with a database called ProQuest. It has millions of archival material not always easy to find.

One of our first searches is a combination of random words: Central Park – Molly – 2001 – abandoned.

Thousands of results consisting of scholarly journals, books and newspapers pop up — and many don’t have anything to do with what we’re looking for.

But then there’s this.

A headline that reads: A new haven for Molly.

It was published in Volume 236 – Issue 1 – of the Good Housekeeping Magazine.

Dated January 2003.

How the heck did we miss it?

Sagine: The story opens with an anecdote about a quote, unnamed and unloved baby born on a rock in New York’s Central Park to a quote, homeless pregnant teenager.

It reads like most of the Safe Haven messaging we’ve seen — placing the attention on the baby, not the mother.

It then introduces the baby’s adoptive parents: Carolyn and Jim of Long Island, New York.

The couple previously adopted two boys and were looking to add a third child to their family — one they could quote, dress in pink.

They didn’t hear about Molly until five days after the news spread.

MUSIC OUT

The story says they got a call from a family services agent with connections to New York City’s foster-care system — and they eventually decided to adopt the baby.

We realize we were off on Molly’s last name by a few letters.

We call who we think is the right Molly multiple times.

PHONE RINGING

We try to leave a voicemail — the inbox is full.

VOICEMAIL

We send a long text message — no response.

We think — maybe it’s the wrong number.

Maybe she’s busy.

Maybe she sees our calls, reads our messages and doesn’t want to talk to us.

MUSIC

Sagine: Hi there.

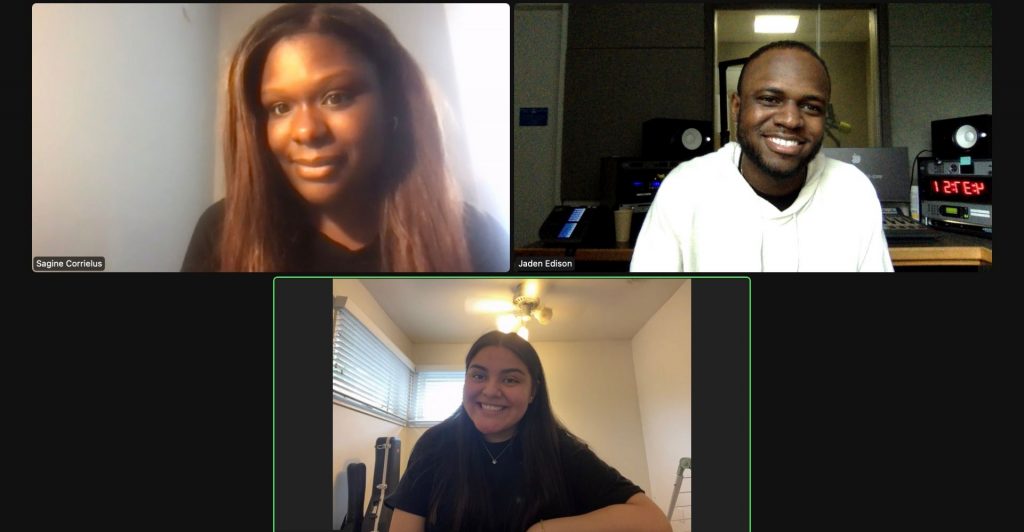

Jaden: I think her audio is connecting. What’s going on Molly; how are you doing?

Sagine: Hey, how are you?

Molly: How are you?

Jaden: But then we get in touch with her after finding her on social media.

Sagine: We’ve been, like, writing this story for months.

Before we know it, we’re on a video call with the baby, now a 20-year-old woman, born on a rock in Central Park.

Sagine Corrielus, Jaden Edison, and Molly.

Molly: I’ve, like, always been aware of, like, the full details of it — like, the birth, the adoption, everything. My family was always very open about that.

She tells us how surprised she and her mom were when we reached out.

How she has a passion for theater.

How she’s graduating from community college and wants to go get her bachelor’s degree.

How her classmates and teachers don’t always believe that she was born on a rock — when she tells them during class icebreakers.

Molly: It’s actually funny because, about a month ago, I was explaining, like re-explaining, the whole story to one of my professors. And I was like, because everyone, again, thinks that I’m making this up.

So I always have to pull up the proof. And I was — I haven’t, like, read the articles, and I don’t actively read them because I don’t have to explain to people in my life often — but I was reading them.

And I was like, ‘Oh, this is not correct.’ So that was very weird to have all these things published about me and have very few of them actually be correct.

Most importantly, she tells us that she’s doing okay.

And that she’s living a happy life.

MUSIC OUT

Correcting the record

Jaden: By saying she was abandoned, almost every article we read about Molly was inaccurate.

We know that she was relinquished under Safe Haven.

It didn’t make sense to us how everyone else got such an important detail wrong.

Rocco Parascandola: There was a lot about it early on that changed, sort of the nature of police reporting, a lot of the preliminary information is wrong.

Sagine: That’s Rocco Parascandola again, one of the reporters who covered the story in 2001. We spoke to him at police headquarters near the Brooklyn Bridge.

Rocco: Abandonment, you know, would not be the right term.

Particularly if the mother has the good of the child in her mind and is putting her with someone who she knows or believes can take care of the child.

Witnesses lie. Police are responding to a 911 call about ‘A’ and it’s really ‘B,’ so a lot of times the information changes.

So that might be, you know, the reason for it.

Another reason wrong information gets out is because journalists don’t always apply scrutiny to who they deem official sources.

Bobby Cuza, the other reporter who covered the story, says that police accounts tend to dominate the narrative when there’s little information and few witnesses.

Bobby Cuza: Because they’re the ones who investigated it.

We weren’t there at the time.

And we’re only really hearing one side of the story.

So we might hear a version of the story.

And that may have been the case here that maybe paints this woman in a more unfavorable light because the police are looking at this through a different lens.

Jaden: We sent the NYPD an open records request for more information.

We wanted to see an original police report — or the press release they sent to newsrooms back then.

But so far, we haven’t gotten a response.

Rocco and Bobby’s story, however, is riddled with attributions to police.

What we also know for certain is this — two days after Molly was born, 9/11 happened.

Bobby: I mean it crowded out any other news story and just completely erased anything that was going on prior to that.

MUSIC

When 9/11 happened — I was only 2 years old living in Chicago.

I don’t remember anything, but my mom says I was at daycare when the first plane hit.

Sagine: I remember just a bit more. I was 5, living in Brooklyn. The smoke was so thick you could see it from my neighborhood all the way across the Brooklyn Bridge.

My school made the announcement that something big had happened, but I didn’t understand what was going on until my dad picked me up from school that day.

Jaden: Molly on the other hand — was only a couple days old.

Probably somewhere asleep in the hospital.

She didn’t have the slightest clue about what was taking place.

The people around her thought she was left to die on a rock in Central Park.

But that wasn’t true.

And if we were writing that story today, it would have sounded something like this.

Molly: A baby girl was born on a rock in Central Park yesterday. Her mother called Tim Jaccard, a Nassau County police medic, to help with the delivery.

Jaccard founded the National Safe Haven Alliance, an organization that helps mothers legally and safely relinquish their babies.

The seven-pound newborn was taken to St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital.

The mother’s whereabouts and health status are unknown.

There isn’t any information available regarding why she opted to relinquish the baby under the recently-passed Safe Haven law in New York — no explanation for why the mother did what she did.

But in the end, she made sure her baby was safe.

MUSIC ENDS/OUTRO MUSIC COMES IN

Credits

Sagine: Shoe Leather is a production of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by Sagine Corrielus and Jaden Edison.

Jaden: Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Rachel Quester and Peter Leonard are our co-professors. Special thanks to Columbia Digital Librarian Michelle Wilson, Professor Dale Maharidge, Chiara Eisner and Michael Barbaro.

Sagine: Shoe Leather’s theme music — ‘Squeegees’ — is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller, remixed by Peter Leonard.

Other Music by Blue Dot Sessions.

Jaden: Our season three graphic was created by Maria Fernanda Erives.

To learn more about Shoe Leather and this episode go to our website shoeleather.org.

MUSIC ENDS