In 1971, Patrick Critton helped rob a bank as part of a Black separatist group and, to escape capture, became the first person to successfully hijack a plane in Canada.

He spent 30 years on the run until he was arrested and pleaded not guilty on Sept. 10, 2001. Less than 24 hours later, the 9/11 attacks left him as an ironic footnote in history.

“The Other Hijacker” is a story about dedication and pursuit, about how far people are willing to go – and what they’re willing to sacrifice – for their beliefs. But it’s also about identity and redemption, about how the only way to determine a legacy is to keep writing the next chapter.

TRANSCRIPT

MIKE DAVIS: Patrick Critton has never considered himself a criminal. Not for the things he’s done in Tanzania. Or in Cuba. Or in Canada. Or in Harlem.

Not even as he stood before a judge in a Manhattan courtroom on September 10, 2001.

1010 WINS NEWSREEL: “A former New York City school teacher appeared before a federal judge in Manhattan yesterday accused of being a fugitive hijacker and bank robber…”

MIKE: To Patrick, it was all the same mission – the liberation of Black people in the United States.

1010 WINS NEWSREEL: “Authorities say they were led to Critton after his fingerprints on file with the Board of Ed. matched those on a 30-year-old arrest warrant. Sources tell the New York Post that…”

MUSIC IN – “SUNDAY LIGHTS”

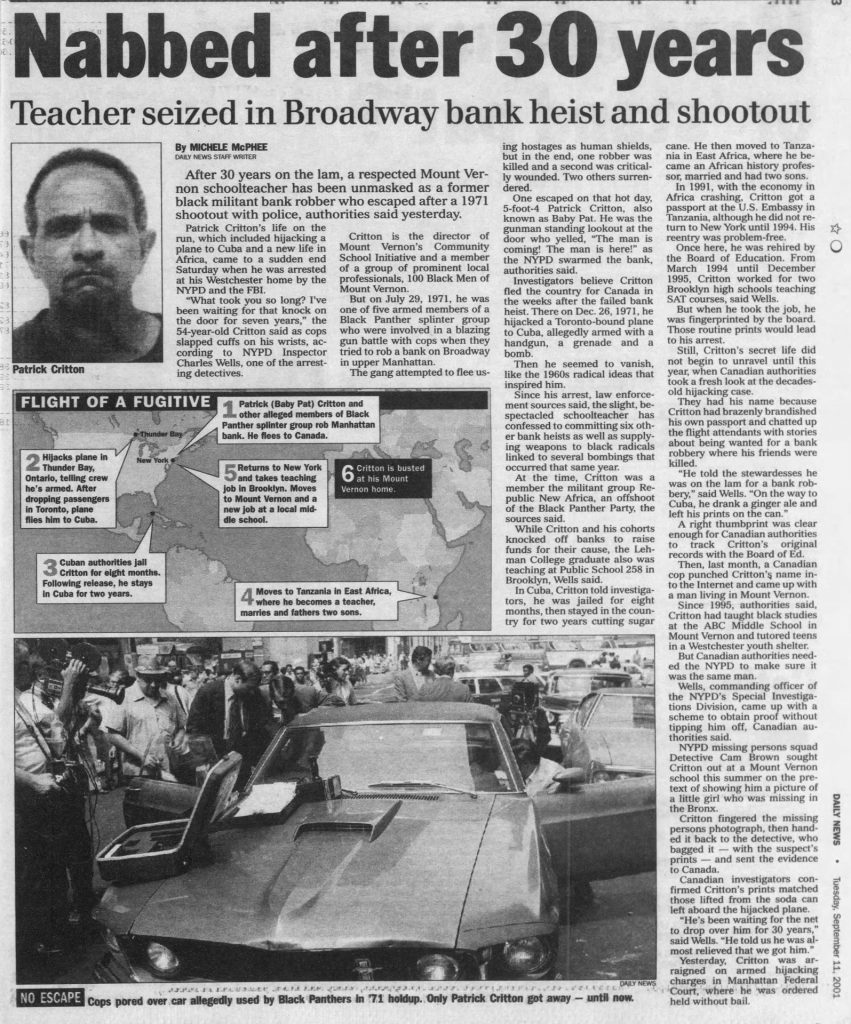

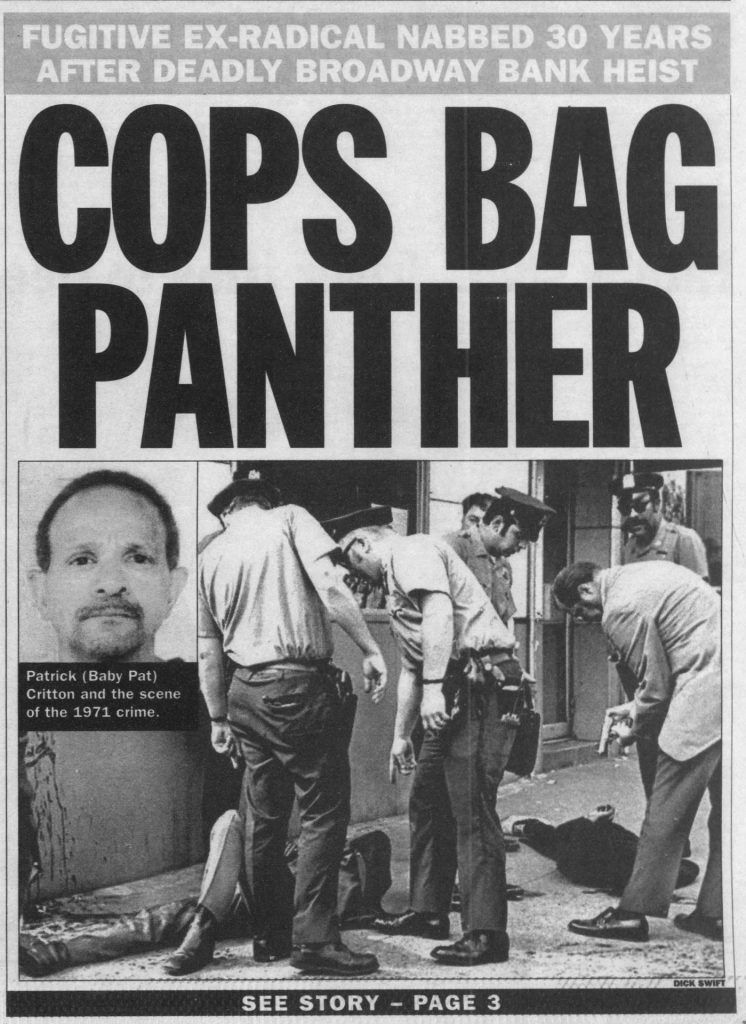

CHANTAL VACA: The next morning, Patrick’s picture was everywhere – The New York Times and the Daily News and the New York Post. They outlined the charges against him. He had helped rob a bank. He was the only person to ever successfully hijack a plane in Canada.

And he’d been on the run for 30 years.

As Patrick sipped his coffee in his jail cell that morning, he heard an explosion. It was loud, but muted.

By the time 1010 WINS finished the news update, the North Tower of the World Trade Center was already on fire. News organizations across the city and the country were mobilizing to find out what just happened.

The South Tower would be hit just 17 minutes later.

MIKE: For the first time, hijacking an airplane wasn’t just seen as a getaway. Or a way to get rich quick. It was now a way to get your hands on a weapon of mass destruction.

In an instant, Patrick Critton became just an ironic footnote in history. And his face all but disappeared from the news cycle.

MUSIC OUT – “SUNDAY LIGHTS”

CHANTAL: In trying to piece together Patrick’s story, we read dozens of news articles – about Patrick. About the Black liberation movement. About 9/11. We read entire books about the history of airplane hijacking and even Patrick’s own self-published autobiography. We examined court documents and public records and even knocked on a few doors.

AMBIENT SOUND: An apartment door is unlocked and slowly opens.

CHANTAL: “Hey! Are you Patrick?”

MIKE: What we found was a story that developed over four countries and three continents. It’s 30 years in the making. It even involves the singer Mary J. Blige.

MUSIC IN – “SQUEEGEES”

CHANTAL: We wanted to find Patrick. To talk to him. To find out why he did what he did. To understand what it’s like to know so intimately what you’re supposed to do with your life.

And to become so determined, you’ll do just about anything in its pursuit.

PATRICK CRITTON: “If you’re looking at, like, ‘you broke the law,’ Bonnie and Clyde? That’s all bullshit. I’ll be quite frank with you: I’m 74. I’m an educator and a freedom fighter.”

CHANTAL: This is a story about dedication and reckless abandon. About how far people are willing to go – and how much they’re willing to sacrifice – for what they believe in.

MIKE: But this is also about redemption. About how our stories remain unfinished as long as we’re willing to keep writing the next chapter.

I’m Mike Davis…

CHANTAL: …and I’m Chantal Vaca. This is Shoe Leather, an investigative podcast from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. We dig up stories from New York City’s past to find out how yesterday’s news affects us today.

MIKE: This season, we’re zeroing in on one day: September 10, 2001. We’re exploring what people were talking about on the subways and the elevators and the sidewalks of New York City, the day before the world stood still and everything changed forever.

CHANTAL: This is Shoe Leather, Season 3: The Day Before. You’re listening to “The Other Hijacker.”

‘Kubanbanya’

AMBIENT SOUND: Crowds milling about along the sidewalks in Harlem, 125th Street

CHANTAL VACA: I live a few blocks away from 125th Street in Harlem. Most days, vendors line the edge of the sidewalks. They sell hats. Sunglasses. Incense. T-shirts.

One shirt says “just a kid from Harlem.”

To understand what drove Patrick Critton to do the things he did, you need to remember that – at one point – he was just a kid from Harlem.

He was born in Harlem Hospital on July 14, 1947, alongside his twin brother, Frank. And as they entered the world, the civil rights movement took flight.

MIKE DAVIS: When Patrick was just a year old, President Harry Truman ended segregation in the military.

U.S. PRESIDENT HARRY TRUMAN: “It is my deep conviction that we have reached a turning point in the long history of our country’s efforts to guarantee freedom and equality to all our citizens.”

And when he was just six years old, the Supreme Court ruled against school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education.

INTERVIEWER: “What about you, sir? Do you think the colored students will show up?”

PARENT: “If I’ve got anything to do with it, they won’t show up. … Well, I think it’s a breaking point, the school integration. I just don’t feel they have the right to go to school with them.”

CHANTAL: Patrick and Frank were good students – in the top quarter of their middle school class. By the time they went off to DeWitt Clinton High School, it felt like they were entering a whole new world.

It was in a mostly white neighborhood in the Bronx. But schools across the country were still in the process of desegregating.

Patrick experienced it firsthand.

MIKE: They were the only Black students in their honors classes and Patrick also served on the student court, where he had to dole out punishment to other students when they broke the rules. He always looked out for the other Black kids in school, though. There were only a few of them.

As Patrick focused on his studies, the civil rights movement grew across the U.S.

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR: “‘I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.”

CHANTAL: Patrick went on to Hunter College in the Bronx. Today, it’s known as Lehman College.

He became a leader of the Black student union. It was called Kubanbanya. It’s a Swahili word. It means “those who are seeking.”

But when Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in 1968, Patrick began immersing himself further into the underground movement.

The militant movement.

He found out about a new group of Black militants in Detroit. They wanted to create an independent Black nation in the south.

MILTON HENRY: “We cannot possibly find freedom within the system. Separation is essential for us – absolutely essential if we are to require independence and freedom. And that’s what we’re after.”

The group was called the Republic of New Afrika.

And by the time Patrick graduated in 1969, he was fully submerged.

MUSIC IN – “ARIZONA MOON”

PAUL WILLIAMS: “When you’re young, if you get associated with these strong commitments in terms of political action, you’re subject to be radicalized one way or the other.”

MIKE: Paul Williams came to New York in the 1970s to get his law degree at Columbia. Later, he would become a leader and eventually president of the New York chapter of One Hundred Black Men. That’s a nonprofit that provides mentorship and other leadership programs in Black communities.

Paul and Patrick would eventually become friends, but they wouldn’t meet for a few decades.

CHANTAL: For the next two years, Patrick lived two lives.

By day, he was a teacher and a youth counselor. He was a family man, with a wife and an infant son.

But at night, he was a soldier in the Republic of New Afrika. He managed three units – keeping inventory of everything they needed. From guns to food. Medical supplies.

And bombs.

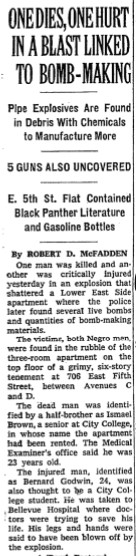

MIKE: Bombs were going off in New York and across the country, hand-made by young Black and white militants in different groups and organizations. They didn’t always share the same ideologies, but there was overlap – like opposing the Vietnam War.

MUSIC OUT – “ARIZONA MOON”

As he drifted off to sleep one night, the phone next to his bed rang. There had been an explosion at one of his bases. East Fifth Street. Greenwich Village.

Two members were making pipe bombs on the top floor of a six-story apartment building. Suddenly, one of the devices exploded. One of Patrick’s comrades died. Another one was taken to the hospital with life-threatening injuries.

It was the second explosion in the Village in less than a month. The first one was caused by a few members of the Weather Underground, another one of those radical militant groups opposed to the Vietnam War.

NEWSREEL: “A series of explosions leveled this Greenwich Village townhouse five days ago. Investigators first thought the blast was caused by leaking gas but, as their search continued, they began finding evidence of explosives. Officials now believe the house was being used as a make-shift bomb factory.”

CHANTAL: The explosion only deepened Patrick’s commitment to the Black liberation movement and the Republic of New Afrika.

MUSIC IN – “GOLDEN GRASS”

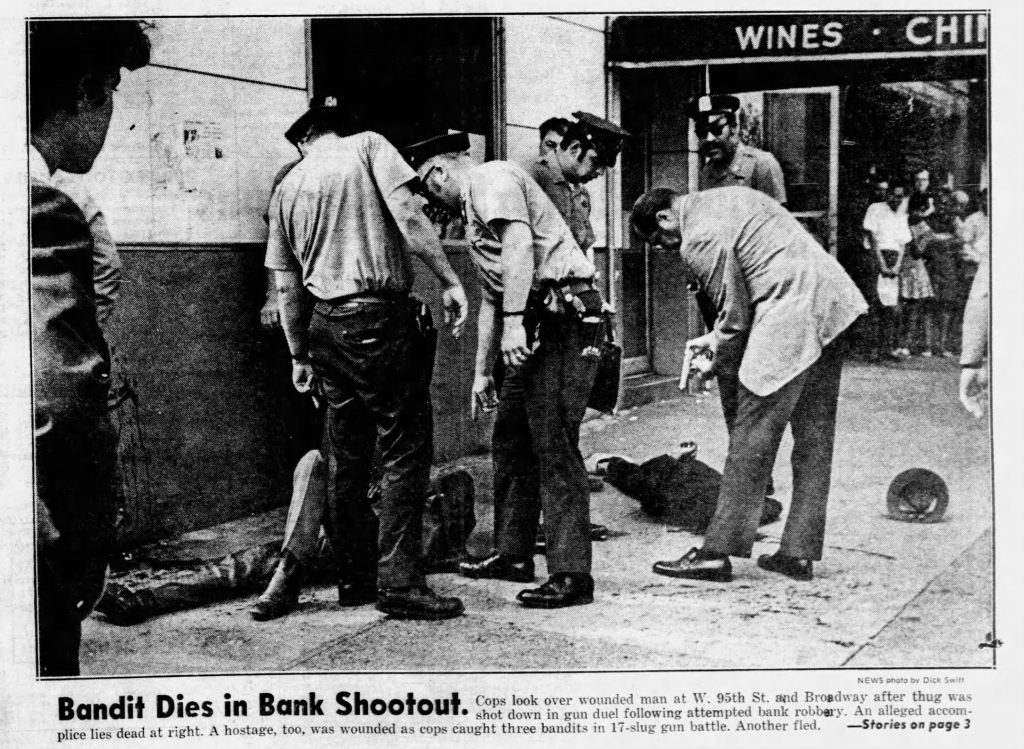

MIKE: On the morning of July 29, 1971, five of Patrick’s comrades walked into the Bankers Trust Company branch on the Upper West Side. They walked past the security guard. He was in on it.

They got in line for the bank tellers…and pulled out their guns. They said: “Nobody move. This is a hold-up.”

They lined up the customers against the wall near the entrance, and they had the tellers go through their cash drawers.

It all seemed to be going smoothly.

CHANTAL: But what they didn’t realize was that one of the bank employees figured out what was happening before it even started. The silent alarm had been tripped before the robbers even pulled out their guns.

The police were on their way.

Patrick saw them first. He was the lookout. He quickly opened the door and stuck his head inside to alert his comrades.

“The man is coming! The man is here!”

MUSIC OUT – “GOLDEN GRASS”

They were busted.

Patrick turned and ran to one of the getaway cars parked out front. It was a green Ford Mustang. But when he pulled on the door handle, it wouldn’t open. It was locked.

He could wait for the cops to find him or he could keep running, and Patrick ran. He was 24 years old.

MUSIC IN – “GOLDEN GRASS”

MIKE: What happened next at the Bankers Trust was like something out of a movie.

They forced the dozen hostages to form a huge human shield around them and walk up Broadway. They got less than a block.

Someone – no one knows who – fired a shot. And everyone hit the deck. The hostages all dropped to the floor. And now, the police and the robbers opened fire.

When the dust settled, one robber was dead – shot in the chest. Another one was injured. Two more threw down their guns, and were arrested by the cops.

But Patrick Critton? He made it out.

He didn’t think his comrades would rat on him and give up his name, but he couldn’t take any chances.

He needed to get somewhere the police wouldn’t follow.

His only options were to get found or to flee.

MUSIC OUT – “GOLDEN GRASS”

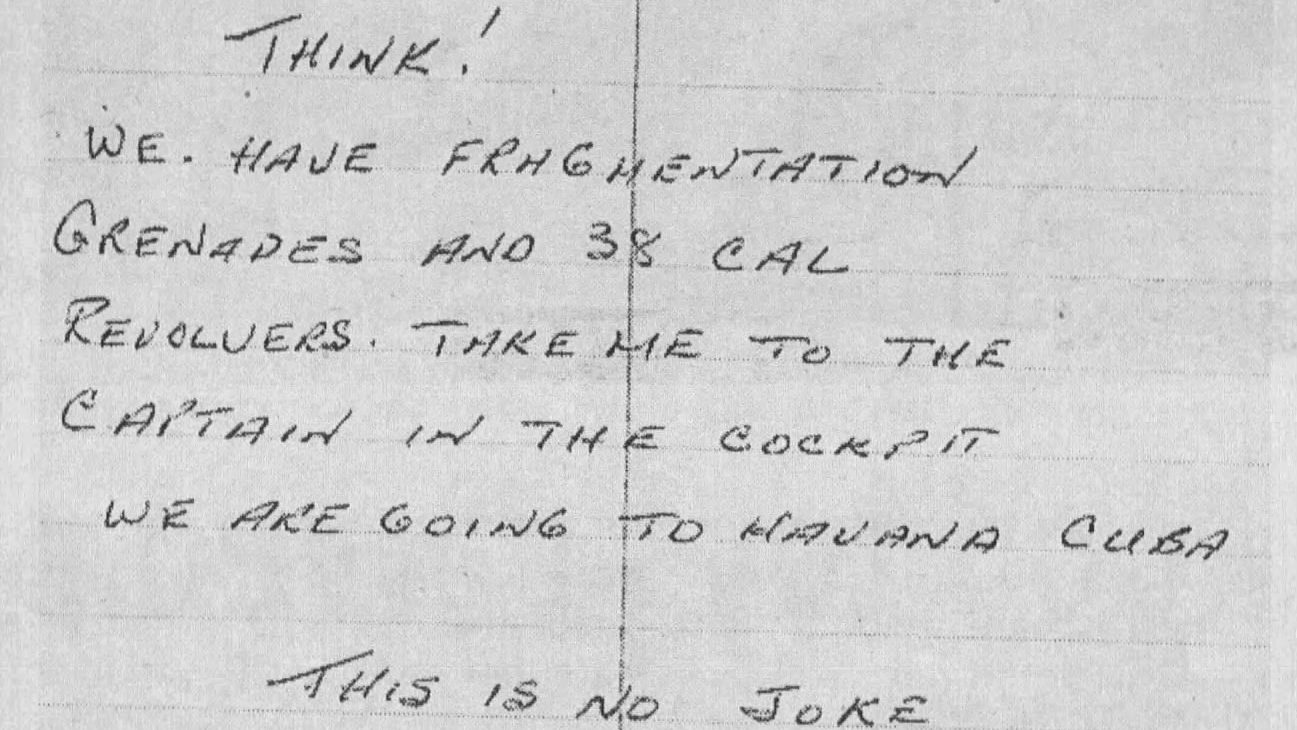

CHANTAL: It was Christmas Eve 1971. Patrick got onto a bus with 500 bucks in his pocket, a small gym bag and a Christmas gift. Inside the bag was a gun. Inside the gift box, he’d stashed a grenade.

Nobody searched his bags as the bus crossed the border into Canada. But he didn’t get much farther than that.

A snowstorm left everyone stranded in Thunder Bay, Ontario. Whatever plans Patrick may have had were completely derailed by the storm.

It was Christmas Day.

Patrick was thousands of miles away from his family and his fellow soldiers. He was still on the run, too. And now, there was nowhere to go.

At least by bus.

Air Canada Flight 932

CHANTAL VACA: Patrick’s ticket was in the first-class cabin. Away from the rest of the passengers. Close to the cockpit.

As Air Canada Flight 932 took off from Thunder Bay, Ontario, he passed the time the way any airline passenger would. He read magazines. He sipped scotch.

And five minutes before the plane landed, Patrick got out of his seat and walked toward the cockpit.

He found a flight attendant in the little kitchenette on the way. Just on the other side of the curtain from the cabin.

HELGA WETTERINGS: “This man came up and he handed the stewardess who was standing beside me a piece of paper.”

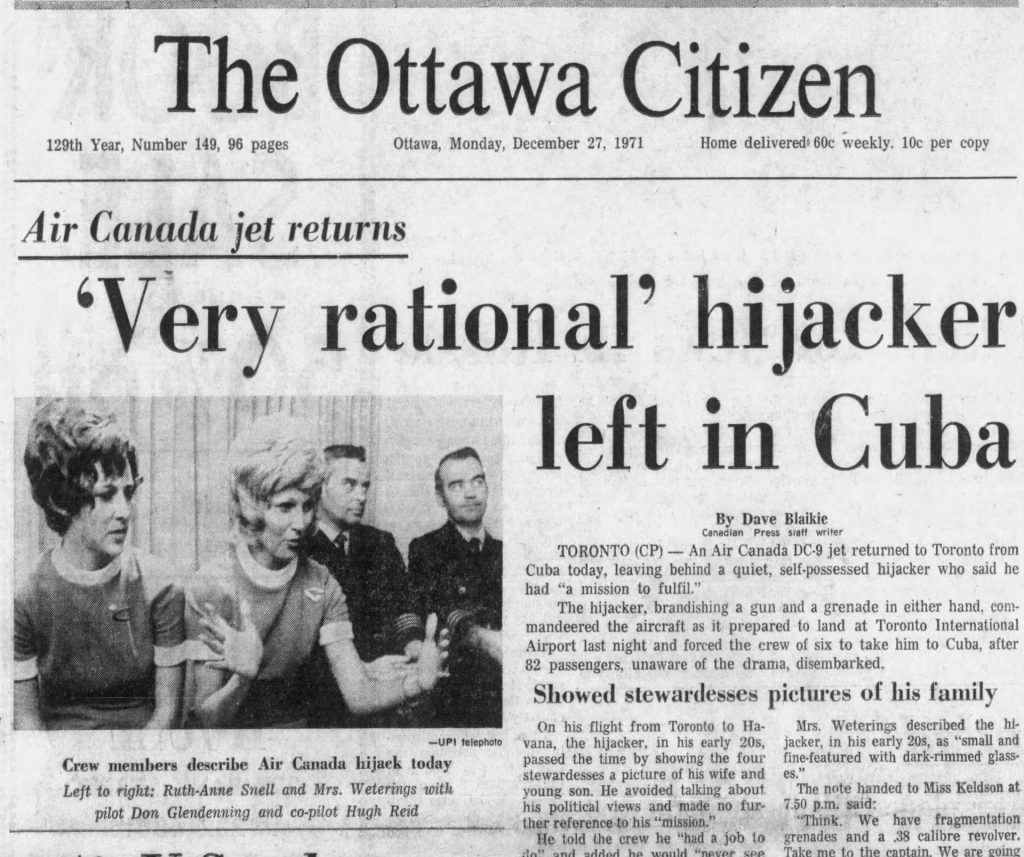

MIKE DAVIS: Helga Wetterings was another flight attendant on Air Canada Flight 932. That’s her talking at a press conference the next day.

Patrick wrote his note in all capital letters. And it started with one word: “Think!” With an exclamation point.

“We have fragmentation grenade and .38 caliber revolvers. Take me to the captain in the cockpit. We are going to Havana, Cuba.”

“This is no joke.”

HELGA WETTERINGS: “And at the same minute, he pulled out his gun, and he said to the stewardess, ‘Would you take this paper to the captain?’ Well, that was it.”

CHANTAL: That was it. Air Canada Flight 932 was being hijacked.

MIKE: But it wasn’t like the situations you’re probably thinking about when you hear about an airplane hijacking.

MUSIC IN – “APOLLO DIEDRE”

There was no tense showdown with any air marshals. There wasn’t a shootout. It certainly wasn’t like 9/11. The passengers disembarked as scheduled in Toronto. They had no idea they were technically hostages.

Patrick barely even threatened the crew with the gun. Or the grenade.

REPORTER: “Did you see a grenade?”

HELGA WETTERINGS: “Only afterwards, after we had taken off. He was holding the gun in his right hand and a grenade in the other hand, in the left hand.”

He didn’t wait to find out if there was even enough fuel onboard the plane. After a few minutes, Patrick told the pilot – Captain Donald Glendenning – to hit the throttle and take off.

CHANTAL: In Toronto, the control tower tried to negotiate with Patrick. They offered him money, but Patrick refused.

All he wanted was enough fuel to get to Cuba.

The control tower numbered the plane “Flight 67.” Nonstop, from Toronto to Havana.

MUSIC OUT – “APOLO DIEDRE”

REPORTER: “What would you describe the mood of the man as?”

CAPT. DONALD GLENDENNING: “Well, I didn’t get to talk to him too much, really. He just seemed fairly normal, really. He just wanted to go somewhere.”

REPORTER: “Did he appear nervous –”

CAPT. DONALD GLENDENNING: “Not particularly.”

REPORTER: “– or scared?”

CAPT. DONALD GLENDENNING: “Not really.”

CHANTAL: But Patrick did talk to the flight attendants. He showed them pictures of his infant son. They talked about their personal lives. Their astrological signs. The Vietnam War. Patrick’s life in Harlem.

Patrick became so friendly with the flight crew that he even asked for a can of Fanta ginger ale as the plane headed toward Cuba.

MIKE: Air Canada Flight 67 arrived at Jose Marti International Airport in Havana just after midnight. When the door opened, Patrick saw a man in a suit and tie run toward the plane. He was accompanied by an armed guard.

Patrick unloaded the revolver and handed it over. Along with the grenade. The Cuban officials escorted him off the plane and officially into their custody.

He wished the flight attendants a happy new year and told them to write him letters.

CHANTAL: And then, as far as the Canadian government was concerned, Patrick Critton walked into the hot, humid midnight air and disappeared for the next 30 years.

‘The golden age of skyjacking’

MIKE DAVIS: I know what you’re probably thinking: This escalated pretty quickly, right

One day, Patrick is on the run from the cops. The next day, he decides he’s going to try to hijack an airplane? To another country?

CHANTAL VACA: But you have to realize something about the times Patrick was living in. If you were one of those revolutionary types, hijacking an airplane didn’t seem that far-fetched.

In fact…it was kind of easy to pull off

AMBIENT SOUND: TSA security checkpoint at an airport

CHANTAL: Think about the last time you were at the airport. You probably had to wait in a long line.

Shoes off. Belt off.

You had to make sure your shampoo and your toothpaste were in those little tiny bottles that leak everywhere.

MIKE: You probably walked through a metal detector. Maybe twice, because you forgot your keys in your pocket.

But in 1971, Patrick didn’t have to go through any of that.

Air travel was……just sort of different.

PAN-AM ADVERTISEMENT: “Chances are you’ve heard about the plane with the spiral staircase in first class…“

CHANTAL: It was seen as a more refined way of travel.

PAN-AM ADVERTISEMENT: “…The plane with the two wide aisles and the three widescreen movies and the 8-foot ceilings in economy…”

MIKE: People flew on airplanes not just because they were fast, but because they were fancy. Luxurious.

PAN-AM ADVERTISEMENT: “…Pan-Am will bring you the world’s first 747.”

CHANTAL: The whole point was to get you on the airplane as quickly and painlessly as possible.

Nobody bothered to check your luggage to make sure your liquids were in a clear bag. Nobody checked for anything.

Not even a gun. Or a grenade.

MIKE: “What…what was it that drew them to hijacking airplanes specifically?”

BRENDAN KOERNER: “Well, I think one thing was just that it was really easy to do.”

MIKE: That’s author and journalist Brendan Koerner. His 2013 book “The Skies Belong to Us” is all about these hijackings that happened in the sixties and seventies. They even had a fun, sexy name: “Skyjackings.”

But when Brendan talks about them, he uses one word in particular:

BRENDAN KOERNER: “So, I’m going to confine what I say to the phenomenon in America.”

CHANTAL: A phenomenon.

From 1968 to 1972, there were 130 airplane hijackings on flights departing from American airports.

That’s one hijacking every other week.

BRENDAN KOERNER: “There was really no security, as we understand it, in the modern context. There was no search. There were no magnetometers. There were no bag searches. You didn’t really have to show ID most of the time. So it was very easy to do.”

MUSIC IN – “HARDBOIL”

UNCREDITED NEWSREEL: “A 707 jet is the newest target of hijackers, an incredible fiction-like attempt at piracy…”

NBC NEWSREEL: “Northwest Airlines 734 bound for Miami by way of Chicago was hijacked this afternoon shortly after it left Minneapolis…”

UNCREDITED NEWSREEL #2: “…a nine-hour ordeal of terror in El Paso as a Continental Airlines jet is hijacked by a father and his son. Government agents machine-gunned the plane’s tires to prevent it taking off…”

GETTY NEWSREEL: “…described as very cool, waited with the rest of the 95 passengers for an answer to his demand: $500,000 in cash and four parachutes plus…”

GETTY NEWSREEL #2: “He stuck the gun in my back, he said ‘you’re not going to be hurt if you do what I say. Get me to the cockpit.’”

MUSIC OUT – “HARDBOIL”

MIKE: Airlines had a policy of maximum cooperation. They told their flight crews to do whatever the hijackers wanted.

As long as passengers weren’t hurt and planes stayed in the air, airlines were willing to comply with hijackers’ demands.

BRENDAN KOERNER: “Because there were so few instances of hijackers acting violently … The economic calculus was just ‘give them whatever they want, and we’ll get the plane back and everyone will be safe. And this is just the cost of doing business.’”

CHANTAL: It wasn’t until November 1972 when things got serious. A group of hijackers took control of Southern Airways Flight 49.

They threatened to crash the plane into a nuclear reactor in Tennessee unless they got $10 million in ransom money.

BRENDAN KOERNER: “It kind of woke people up to the fact that there was a possibility for a serious mass casualty event if these hijackings were allowed to become even progressively crazier and crazier as happened throughout that year…And so that was really the moment where I think airlines became aware that the risks of not instituting ground security could lead to something that would … pretty much wipe out their industry, perhaps.”

MIKE: Two months later, the Federal Aviation Administration ordered that all airline passengers would have to go through security screenings.

And after all of that – all of that pushback by the airline industry, all of those hijackings – everything went pretty smoothly.

NBC NEWSREEL: “In Cleveland, the new security procedures were initiated Wednesday. …Passengers have been asked to say their goodbyes before reaching the main concourse, which has become the primary security checkpoint. … There was concern that the more detailed screening would delay operations and foul up flight schedules. FAA officials say the two-day trial run seems to have prevented that in Cleveland.”

The number of hijackings on American flights increased every single year from 1968 to 1972.

But in 1973, after security became the norm? The number of hijackings in American airspace dropped to zero. Not a single U.S. flight was hijacked in 1973 or 1974.

CHANTAL: But that didn’t happen until a year after Patrick boarded Air Canada Flight 932, with a gun in his pocket and a grenade in a box wrapped up like a Christmas gift.

In Canada, hijacking a plane wasn’t even technically a crime yet.

Life in exile

CHANTAL VACA: We could dedicate a whole podcast to what happened to Patrick Critton after he stepped off the plane in Havana, Cuba.

But here’s the important part: Life in exile isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

MUSIC IN – “IN THE BOX”

MIKE DAVIS: Patrick only stayed in Cuba for three years. First, in solitary confinement. Then, at the “Hijacker Hotel” in southern Havana.

That’s where the Cuban government put all those starry-eyed revolutionaries who hijacked planes or worse and wound up in Cuba to avoid extradition.

But Patrick got bored pretty quickly. He spent most of his time living in huts and cutting sugar cane and building houses for the Cuban government.

CHANTAL: Patrick did leave Cuba, but he didn’t return to the United States. At least, not yet.

Like many Black liberation activists at the time, his goal was to wind up in Africa. The land of his ancestors.

He went to graduate school in Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania.

And then he rose up the ranks of teaching. He taught English language classes and literature. He became the head of the history department.

He was even named the headmaster of a private school.

MIKE: And he also found the one thing he thought he’d left behind in New York: A family.

He met his wife, who worked for the Tanzanian government. They had two sons.

MUSIC OUT – “IN THE BOX”

There wasn’t any one particular reason why Patrick decided to return to the United States after 20 years. But consider what he did next: He went back to work. The work. Teaching. Education.

In his autobiography, he writes: “I was tired of exile and willing to face captivity in a prisoner of war cell.”

Patrick was finally tired of running and he was willing to face jail time.

He boarded a flight from Arusha and landed at JFK International Airport on May 13, 1994. Nobody stopped him at customs. There weren’t any federal agents waiting to pick him up.

He was just a guy on a plane.

Returning home. Getting back to work.

Hiding in plain sight

AMBIENT SOUND: Construction equipment, traffic and birds in Mount Vernon, N.Y.

CHANTAL VACA: Mount Vernon is a suburb just outside New York City. About six or seven miles from Manhattan. 28 minutes on the Metro North.

MIKE DAVIS: “The houses seem closer together than they were before, I think…”

MIKE: It’s an old school suburb. Working class. There aren’t any gated communities, with those cookie-cutter colonials on three acres of land.

CHANTAL: “There’s, like, power lines on the streets, or lining the streets.”

MIKE: “You can definitely tell that some of these houses have been here way longer than others, you know? They seem a little older and more classic.”

MUSIC IN – “FUNK AND FLASH”

CHANTAL: Here’s the other thing about Mount Vernon: Race is built into the DNA of this place.

You know those old cliches, about the “good side of the tracks” and the “bad side of the tracks?” That’s Mount Vernon.

And the people who decided “good” and “bad” were probably the white people who wound up on the north side of the tracks.

MIKE: If there’s any common ground, it’s this: When families leave cities for the greener, quieter suburbs, they’re usually looking for better schools, too.

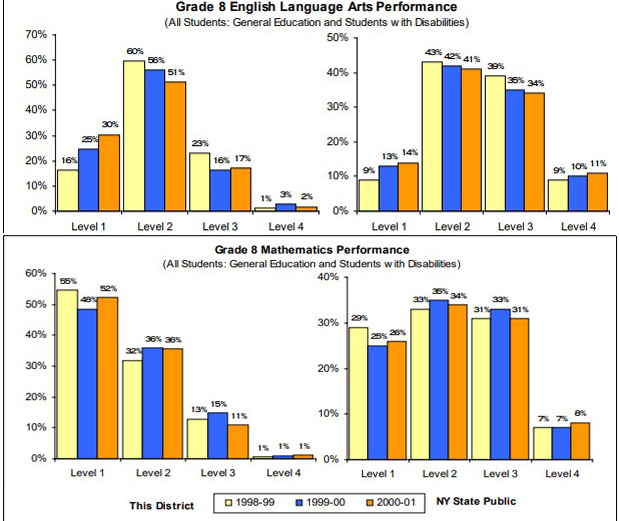

And in the mid-nineties, Mount Vernon schools needed help.

CHANTAL: And at that time, nearly 60% of the city’s population was Black. So those issues in the school system were mostly faced by Black kids.

MUSIC OUT – “FUNK AND FLASH”

PAUL WILLIAMS: “They had problems in the schools just maintaining appropriate averages and keeping kids in school. There was a scenario that was consistent in most of these urban areas, which was that Black boys of color were just not graduating.”

MIKE: That’s Paul Williams, again. He’d been named the president of the New York chapter of One Hundred Black Men. And right around this time, the organization got a really big boost.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “We were thinking about expanding our mentoring program to Westchester County. … We got a grant from Mary J. Blige…”

MUSIC IN – “REAL LOVE,” MARY J. BLIGE

CHANTAL: Yeah. THAT Mary J. Blige. “Nine Grammy Awards” Mary J. Blige. “The Queen of Hip-Hop Soul” Mary J. Blige.

MUSIC OUT – “REAL LOVE”

MIKE: That $20,000 grant from Mary J. Blige was the spark, but they still needed volunteers to actually spend one-on-one time with the students.

MUSIC IN – “GAMBOLER”

Luckily, one of their members was already a teacher in Mount Vernon. He worked at A.B. Davis Middle School. He oversaw classes in health and computer literacy for “WestCOP,” a program funded by the United Way.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “He stood out because, first of all, not everybody in the organization was particularly committed to actually rolling up their sleeves and spending that kind of time, number one.”

Everyone around town knew him.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “But number two, he seemed to have a passion for it and seemed to really enjoy it and the responsiveness was great. … And Patrick volunteered to be involved in that and it was a natural role.”

Yup. That Patrick. Patrick Critton, the bank robber. Patrick Critton, the hijacker.

CHANTAL: There was just one, weird thing that Paul noticed. Patrick was happy to volunteer with One Hundred Black Men…but he wanted to stay in the shadows. He wasn’t really interested in any publicity.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “I distinctly remember Patrick had a conversation with me. I was saying, ‘oh, I’m so happy you want to be a part of this. It’s going to be great. It’s going to be new.’ And he said, ‘yeah, Paul, I really want to participate but I want you to know I’m not really looking for any notoriety or anything about this. I just want to participate and do my work. I’m not looking for accolades, basically. I’m not looking for publicity.”

Paul didn’t think anything of it. Patrick’s name had been in the local newspapers a few times for his work in the Mount Vernon schools. He was just being modest.

And when the Queen of Hip-Hop Soul, the nine-time Grammy winner, the pride of Westchester gives you a $20,000 grant, there’s going to be some publicity.

MUSIC OUT – “GAMBOLER”

LEAH RAE: “My editor assigned me a story that was looking at mentoring in the Black community in the business world.”

MIKE: That’s Leah Rae. In March of 2001, she was a reporter at the Westchester Journal News.

LEAH RAE: “And I remember that it was going to be a very short, 10-inch story. So not a lot of time or space to write this thing, but I was going to be talking about mentoring.”

It was a pretty typical reporting experience.

LEAH RAE: “I remember reaching out to a couple of business groups.”

…which led Leah to One Hundred Black Men and Paul Williams…

PAUL WILLIAMS: “I specifically mentioned some of the guys that were running the first group that was going to start this brand new initiative. And I mentioned Patrick’s name.”

…which led her to Patrick Critton.

LEAH RAE: “I don’t remember much about the conversation but I do remember wanting to speak to someone who had experience as a mentor and find out a little bit about what it was all about and what the approach was. So that became a story – not a long one, but it ran in the paper and it ran on the website.”

CHANTAL: The headline was: “One Hundred Black Men expands its outreach efforts toward youth in Westchester,” by Leah Rae. Published on March 25, 2001.

It was just 477 words and Patrick wasn’t mentioned until the third-to-last paragraph. He talks about a possible laundry business that would be run by the program.

He wasn’t even directly quoted.

LEAH RAE: “I remember that initial kind of worry – that the story that I had been assigned about mentoring – about how do you do justice to this story in a small amount of space, and then you’re aware of how much you’re not getting into the story.

“I had no idea how much I was missing.”

MUSIC IN – “GOLDEN GRASS”

MIKE: Patrick’s old apartment building is seven stories tall. It’s three brick buildings on three sides of a square.

There’s a courtyard below, in the middle of everything. It’s the kind of place where anyone can stick their head out the window and see what’s happening down below.

On September 8, 2001, Patrick had just stepped out of the shower in his ground-floor apartment, when there was a knock at the door. The mailman needed him to sign for a package.

CHANTAL: As Patrick stepped forward, six or seven police officers from the NYPD stepped into the apartment. They’d been hiding in the hallway.

It was a ruse.

With his two sons watching, the cops threw Patrick up against a wall. A tall police inspector with a thin mustache put the handcuffs on. His name was Charlie Wells.

INSPECTOR CHARLIE WELLS: “And now, we all just step in, announce ‘Patrick Critton, you’re under arrest.’

Thirty years after the bank robbery. Thirty years after hijacking a plane from Canada to Cuba, Patrick Critton had finally been caught.

CHARLIE WELLS: “And he says: What took you so long?”

MUSIC OUT – “GOLDEN GRASS”

The photo, the fingerprints…and the ginger ale

MIKE DAVIS: What took the cops so long to find Patrick Critton? It had been 30 years.

Let’s go back to 1971 for a minute, to the moment Patrick left the plane in Cuba.

Captain Glendenning ordered the flight crew to collect any materials he’d touched. A pack of cigarettes. A can of Fanta ginger ale. This could all be evidence if and when Patrick was ever caught.

CHANTAL VACA: And then…nothing happened.

MUSIC IN – “MR. MOLE AND SON.”

For the next 30 years, the case of Patrick Critton would gradually become the oldest outstanding file in the Peel Regional Police department.

And then, a detective named Don Jorgensen got involved. He was 40 years old and a sergeant with the Peel Regional Police. Jorgensen decided to take a shot in the dark.

MIKE: All he had was Patrick’s name, date of birth, a passport photo and a brief description of what he looked like.

Jorgensen declined to be interviewed for this podcast.

But in 2003, he appeared in an episode of the true crime series “72 Hours” that focused on the Critton case. It’s one of those really cheesy, melodramatic documentaries. The music makes everything sound like an over-the-top thriller movie.

Anyway, here’s Sgt. Jorgensen in that documentary:

DON JORGENSEN: “I went through the normal police procedures originally and I came up empty. There was no record of Mr. Critton at all, whether it be current or historical.”

What Jorgensen did next was brand new. Something none of his colleagues had ever considered. Maybe because it was new technology. Or maybe they just simply didn’t think about it.

Jorgensen opened a browser window and typed the name “Patrick Critton” into Google.

Remember: This was the year 2001. People still used Yahoo! and AskJeeves and AOL keywords when they searched for information online.

“Google” wasn’t even a verb yet.

DON JORGENSEN: “Usually when you enter something into Google or any other search engine, you get usually an overwhelming number of returns. So when I entered Patrick Critton’s in, I was expecting to get any number of returns. But I actually only got one.”

CHANTAL: It was a newspaper article, published on March 25, 2001. By Leah Rae.

It was about how the organization One Hundred Black Men was expanding its mentoring program to Westchester County. About a $20,000 grant from Mary J. Blige.

And in the third-to-last paragraph, a teacher and mentor named Patrick Critton, who wasn’t even directly quoted.

MIKE: But here’s the thing: How could a couple of detectives in Canada figure out if this teacher in Mount Vernon was the same guy who hijacked a plane 30 years earlier?

That’s where the NYPD and the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force came in.

They actually already had Patrick’s fingerprints on file, from when he applied to work as a teacher – both in 1969 and in 1994. They were a match to that bomb factory on East Fifth Stree, the one that exploded way back in 1970.

And they were a match to the can of Fanta ginger ale from Air Canada Flight 932 in December 1971.

But they needed fingerprints from this guy, in Mount Vernon. And they had to be careful.

CHARLIE WELLS: “How do I know that’s the guy that touched the soda can? So we said, alright so, you ring his bell and say ‘give us your prints,’ then the next day, he’s on a plane.”

MUSIC IN – “CALISSON”

At the time, Inspector Charles Wells was the commanding officer of the Special Investigations Division of the NYPD. He was in charge of 10 different squads, including being the NYPD’s commanding officer of that Joint Terrorism Task Force.

Everyone calls him “Charlie.” And though he didn’t know this “Patrick Critton” guy, the story wasn’t unfamiliar to him.

Wells made a name for himself on the NYPD bomb squad in the 1970s and the 1980s. Nobody needed to explain to Wells what the Republic of New Afrika was. He’d dug through the rubble from some of their bombings.

CHANTAL: Wells also oversaw the NYPD’s surveillance unit. They tailed Patrick for a few weeks, so they knew the route he walked to school every day.

It was a weekday in late August. Patrick was walking along the railroad tracks, the ones that divide the “good” and “bad” parts of Mount Vernon.

And as he got near the train station, a police officer came up to him. He was from the NYPD’s missing persons unit. One of Wells’s guys.

CHARLIE WELLS: “So we have that detective go up to Critton and say, ‘hey mister, could you take a look at this? It’s a little girl that’s missing from the Bronx. Have you seen her?’ So of course he would stop for something like that, like most people would.”

The officer handed over – not just a typical flyer with a grainy picture of the girl – but a glossy 8-by-10 photo. The kind of print that feels a little sticky to the touch.

CHARLIE WELLS: “He grabs the photo and looks at it, says no he hasn’t seen her, hands it back. Now we got his prints.”

Patrick didn’t recognize the girl. He handed back the glossy photograph – and a fresh fingerprint.

It was a match.

MUSIC OUT – “CALISSON”

MIKE: It was Saturday, September 8, 2001. Wells was relaxing in his backyard on Staten Island. He needed a break – at the time, he was working 16 hour days.

But his phone rang. It was the surveillance unit. In Mount Vernon.

Patrick Critton was home. And this time, they had the arrest warrant.

CHARLIE WELLS: “And he’s like this little guy, this ancient guy with little peeper glasses. He looks like somebody’s grandfather. I’m the same exact age as him. He looked like a meek little professor. Not like a terrorist hijacker.”

“So now we all just swarm into the apartment and that’s when he says, ‘I’ve been waiting 30 years for that knock on the door, something like that.’”

CHANTAL: Investigators questioned Patrick for the better part of two days. He talked openly about his life during the upheaval in New York in the Sixties and Seventies.

The Black Panthers. The Republic of New Afrika. The explosion. The bank robbery.

On September 10th, Patrick pleaded “not guilty.” The process of extraditing him to Canada to face trial was underway.

Word of the arrest began to leak out.

And back at the Journal News, Leah Rae got a call from a reporter in Toronto.

LEAH RAE: “And so he asked me if I remembered speaking with Patrick Critton and he began to tell me a little bit about the arrest and what had happened.”

Another reporter reached out to Paul Williams.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “And when I found out why he was calling, it just sort of blew me off my feet. To me, it was a total non sequitur.”

MIKE: But it was more than a shock. It was Paul who’d mentioned Patrick’s name in the first place.

The guilt stayed with him for months, until he managed to get Patrick on the phone. Paul apologized, but Patrick told him not to worry about it.

PAUL WILLIAMS: “He said, ‘I’ve been looking behind my back or looking behind my shoulder every day now and I’m really glad that it’s all over.’ And I will say, that helped me feel better about the situation.

“And he was very almost stoic about it, about the fact that this had caught up with him. But he was ready – quite ready – to address the implications and did just that.”

CHANTAL: The news of Patrick’s arrest was on the front page of the New York Daily News the next day – September 11th.

CHARLIE WELLS: “I’m sitting in my chair, having my coffee, reading the Daily News, going to myself, ‘Oh, this is a good week for the division, we’re on the front page of the Daily News. And my name’s all over page 3, this is going to be a good way to start the week.’ And I got a call from one of my sergeants…”

On New York 1, TV anchor Pat Kiernan picked up a copy of the newspaper to show everyone.

It was 8:45 a.m.

NY1 NEWSREEL: “Front page of the Daily News this morning, the headline is COPS BAG PANTHER. I got a look at this from a distance at first…”

MIKE: By the time this segment was over, the North Tower had already been hit by one plane. Kiernan reported the weather and then cut to commercial.

And then a steady shot of the World Trade Center and a smoke cloud, slowly growing over the city.

CHARLIE WELLS: “I put it on and saw the second plane go into the tower. And then that was it.”

NY1 NEWSREEL: “This is a live picture from our camera on the Empire State Building looking toward the World Trade Center. A report of a three-alarm fire and a report of an explosion in the World Trade Center…”

CNN NEWSREEL: “Oh there’s another one! Another plane just hit! Another plane has just hit! It flew right into the middle of it!”

ABC NEWSREEL: “This is as close as we can get to the base of the World Trade Center, you can see the firemen assembled here, the police officers, FBI agents. And you can see the two towers… A huge explosion now, raining debris on all of us – we better get out of the way!”

Flashbulb moments

MIKE DAVIS: I feel like I’m the last generation who can remember where they were and what they were doing on 9/11. It’s like a flashbulb moment for me.

There’s “before 9/11” and “after 9/11.”

MUSIC IN – “MILKWOOD”

I was raised in the low-lying, coastal part of New Jersey in the shadow of New York City. Everyone knew about a hill or a rooftop or somewhere where – on a clear day – you could see the Manhattan skyline.

Growing up, everyone had a parent – sometimes both – who commuted to the city for work. And everyone knew someone who knew someone who died on 9/11.

As I’ve gotten older, especially as I’ve built my career in journalism, I’ve always wondered about these flashbulb moments. What were people doing? What were they talking about? What was on their mind as the world came crashing down around them?

It almost feels voyeuristic.

And the fact of the matter is that Patrick Critton’s story was page one news in New York City on the morning of September 11th. So there’s a good chance a lot of people were talking about him.

Until suddenly, they weren’t.

LEAH RAE: “Certainly, we would have been planning to look much more deeply into this story and his local work and people who knew him and his story – which is quite a story. But none of that obviously happened.”

PAUL WILLIAMS: “When 9/11 hit, everything just flipped right to 9/11. I don’t really remember much of anything happening besides everybody switching to focus on 9/11 and the impact. Everything else just got obliterated from the scene, if you ask me, in terms of news, issues, interest, focus. At least for a little while.

Two months after 9/11, Patrick was finally extradited to Canada to face charges of kidnapping and extortion. Remember, hijacking an airplane wasn’t technically against the law back in 1971.

There’s a picture of Patrick that ran in the Toronto Star newspaper from the day he arrived in Canada. He’s walking with his arms crossed. Escorted by two officers, including Jorgensen.

Patrick is wearing big, oversized eyeglasses. He has a goatee that looks just a little bit thicker than a five o’clock shadow. Like an eight o’clock shadow.

He’s looking down ever so slightly. When I look at his face, I see someone who’s just taken a deep breath and said “okay, here we go.” It’s got a little bit of resentment in it. A little bit of fear.

You know the phrase, “put on a brave face?” That’s what I get out of Patrick in this photo.

MUSIC OUT – “MILKWOOD”

CHANTAL VACA: The problem facing Patrick was this. He admitted to a whole bunch of other crimes related to his days with the Republic of New Afrika.

The explosion. The bank robbery. Even though the statute of limitations had already passed, all of that stuff was now out in the open.

The legal question was whether Patrick could face a heavier sentence for crimes he’d neer been charged with. Or for charges he’d never been found guilty of.

But there was also a deeper, more human question at the center of this:

Was Patrick really a terrorist? And even if he was, should he be judged by that one day in 1971…or the 30 years that came next?

PAUL WILLIAMS: “If you had any interaction with him, you would not have felt inclined to want to hold something that was so distant in his past against him, number one. And to the extent that he needed to be rehabilitated, he had basically rehabilitated himself over all these years.”

MIKE: We found the sentencing document from Patrick’s case in June 2002. It’s nearly 40 pages long, but about halfway through, the judge makes a pretty declarative statement: that he believes Patrick Critton has been rehabilitated.

Because Patrick spent 30 years working in schools, teaching children in New York and Tanzania, the judge felt there was no reason to lock him in prison for a decade or more – like the prosecution wanted.

Patrick was sentenced to a maximum prison term of five years.

Not everyone agreed with it. For Charlie Wells, the cop who arrested him, it was a joke.

CHARLIE WELLS: “Another different terrorist group, you know, 20 years, 30 years later, gets their hijacked planes and sends them into buildings and kills 3,000 people, right? I guess you can’t really compare what he did, but he still should have gotten more time.”

CHANTAL: Patrick got out of prison after a little bit more than a year, thanks to the time already served since his arrest and bonus time for good behavior. It was June 2003. He went back to Mount Vernon.

Nineteen years later, Mike and I decided we’d try to find him.

Chasing ghosts

MIKE DAVIS: Tracking down Patrick Critton feels like we’re chasing a ghost.

O.K., maybe that’s a little too dramatic. But it feels like we’re chasing Bigfoot. Or Paul Bunyan. Like we’re on the trail of this larger-than-life folk hero.

We’ve talked to Patrick over the phone. Twice.

Both times he wondered why we were so interested in his story.

PATRICK CRITTON: “If you’re looking at, like, ‘you broke the law,’ Bonnie and Clyde? That’s all bullshit. I’ll be quite frank with you. I’m 74. I’m an educator and a freedom fighter.”

MIKE: Both times he set up an appointment for us to call him back so we could talk to him a little bit more in depth.

CHANTAL VACA: Both times…he ghosted us. Left us hanging.

OPERATOR: “Please leave your message for–”

MIKE: “Hey, Patrick. Mike Davis here with Shoe Leather and Columbia University. We had an appointment to talk right now, at 12 o’clock on Friday…”

CHANTAL: But we have an address and, on this cold, frigid Tuesday afternoon, we’re at his apartment building. We think.

CHANTAL: “… we’re going to see if Patrick is at this apartment building. To see if he lives here.”

Outside, the wind is gusting.

CHANTAL: “We’re approaching. There’s a car here. Let’s hope they don’t run me over…they didn’t. Nice.”

It’s so cold that a few people in the lobby shudder as we open the door and let in the cold air.

CHANTAL: “Oh god, it’s so cold.”

Mike heads to the electronic directory and starts to tap through the names in alphabetical order.

CHANTAL: “We’re going to see if we can find his name. Luckily for us –”

MIKE: “Cooks…Critton.”

CHANTAL: “Oh! Oh my gosh! His name is in the thing! We’re about to ring him up!

CHANTAL: “O.K., we’re walking … 2J… 2G … 2I.”

MIKE: Hanging next to Patrick Critton’s front door is a paper heart with three little roses pinned on top. Like a leftover decoration from Valentine’s Day.

On the other side is a doorbell. Chantal rings it.

CHANTAL: “I’ll try the doorbell.”

A short, Black man answers the door in a bright red sweatsuit. He has a pencil behind his ear. And a smile on his face. Like he knew we were coming.

CHANTAL: “Hey!”

PATRICK CRITTON: “How you doing?”

CHANTAL: Are you Patrick?

PATRICK CRITTON: “Yes, I am.”

CHANTAL: “Oh my gosh, it’s so nice to meet you. I’m Chantal.”

CHANTAL: He refuses to shake hands with me. He says it’s because of his fear of COVID-19.

PATRICK CRITTON: “You can’t come in, but I did want to get a look at your face.”

MIKE: We talk to Patrick in his hallway for about a half-hour, while he leans on his doorframe.

At times, it’s a little tense.

He says the only reason he published his autobiography – the book that Chantal and I devoured – was because he didn’t want a white man to publish a book about him first.

PATRICK CRITTON: “But let’s be clear, I only wrote the book because I didn’t a white man to write about me.”

He says this while making direct eye contact with me – a white man, trying to make a podcast about him.

But after a few minutes, he warms up. We talk about other neighborhoods in Westchester and about the general awkwardness that comes with knocking on a stranger’s door.

The podcast is called “Shoe Leather,” after all.

CHANTAL: When I tell him I live in Harlem, he pokes some fun at me.

PATRICK CRITTON: Why do you live with the Blacks?”

CHANTAL: “Well, it’s convenient for me to get to school, it’s only a 20-minute walk.”

PATRICK CRITTON: “Really? But isn’t it dangerous?”

CHANTAL: “I don’t feel like I’m in danger–

PATRICK CRITTON: “O.K., I’m just wondering, I talk shit.”

CHANTAL: “I will say though, one thing for me is I like hearing people speak Spanish, just casually in the street. It’s nice.”

And when I brought up my hometown in the suburbs of Chicago, he laughed. The Weather Underground was pretty active in the Midwest. That’s the other group who accidentally blew up a New York apartment.

PATRICK CRITTON: “When the base blew up they issued a proclamation. The Weather Underground… ‘Hey, handle those explosives carefully You’ll blow your fucking ass up!’ We did! They did!

By the time we’re getting ready to leave, it feels like we’ve made a connection with him.

PATRICK CRITTON: “The vibe is good. I’m a very ‘vibe’ person and I could have said ‘get the fuck out of here.’ But that’s not me.”

He likes our vibe so much, he asks if we want to take a photograph. So I pull my phone out and take a selfie with him, Mike and I sandwiching Patrick. He’s a head shorter than Mike. He and I are about the same height.

We’re all smiling.

MIKE: He tells us to come back on Friday. That he’s going to take us out to his favorite bar.

He makes it very clear, though: This isn’t going to be a normal interview. It’s a conversation – three people talking about their lives and their experiences.

CHANTAL: And then…he says he’ll call us on Thursday. Just to set up details, about when and where to meet.

We’d heard that before.

OPERATOR: “Please left your message for–”

MIKE: “Mike Davis here again with Columbia University and the Shoe Leather podcast, hoping to set up…”

MUSIC IN – “SUNDAY LIGHTS”

MIKE: Patrick never called us. And he didn’t pick up when we called him. We haven’t spoken to him since that day in his apartment hallway, when he told us how he liked our vibe.

CHANTAL: It’s a little disappointing. We thought there was something inherently human in Patrick’s story. It’s about a guy who believed so strongly that he needed to educate his people, to bring them up out of oppression, that he hijacked a plane. Fled across the world.

And when he built himself a whole new life, he was willing to put that at risk again just because he felt such a calling to do this kind of work.

MIKE: So maybe it’s not that weird that Patrick never sat down with us, never gave us the long yarn about his life. About the things he did. About 9/11. About what he learned along the way.

Maybe Patrick isn’t ready to tell his story this kind of way. Maybe he never will be.

Or maybe, just maybe, the story of Patrick Critton is still being written.

MUSIC OUT – “SUNDAY LIGHTS”

MUSIC IN – “SQUEEGEES”

MIKE: “Shoe Leather” is a production of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. This episode was reported, written and produced by me, Mike Davis…

CHANTAL: …and me, Chantal Vaca.

Joanne Faryon is our executive producer and professor. Rachel Quester and Peter Leonard are our co-professors. The entire Shoe Leather team would like to offer a special thanks to Columbia Digital Librarian Michelle Wilson, Professor Dale Maharidge, Chiara Eisner of The State and Michael Barbaro of The Daily.

MIKE: A few resources proved critical to us as we researched, reported, wrote and produced “The Other Hijacker”: The Skies Belong To Us: Love and Terror in the Golden Age of Skyjacking, by Brendan I. Koerner, In Plane Sight, by the late Bob Mitchell and, of course, Lion in the Foliage, Full Moon in the Sky, by Patrick Critton.

Special thanks to Toronto Star city hall bureau chief David Rider.

CHANTAL: Shoe Leather’s theme music, “Squeegees,” is by Ben Lewis, Doron Zounes and Camille Miller, remixed by Peter Leonard.

All other music by Blue Dot Sessions … except “Real Love,” written by Cory Rooney and Mark Morales and performed by the one and only Mary J. Blige.

MIKE: Our Season 3 graphic was created by Maria Fernanda Erives.

To learn more about Shoe Leather and this episode go to our website, shoeleather.org.

MIKE DAVIS is a part-time student at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and full-time reporter for the Asbury Park Press, where his investigative reporting has changed laws and won awards that make his parents very proud. He’s proud to serve as vice chair of the APP-MCJ Guild, a labor union representing journalists at the Asbury Park Press, Courier News and The Home News Tribune through the NewsGuild of New York. This is his first audio story.

Mike is a proud son of New Jersey, with a bachelor’s degree from Rutgers University, a dog named after a Bruce Springsteen song and a lifelong toxic relationship with the New York Mets. Connect via Twitter and LinkedIn or email him at mike.davis@columbia.edu.

CHANTAL VACA will graduate from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in May 2022 and will soon join Futuro Media as a full-time summer correspondent for Latino Rebels. Previously, she worked as a producer for The 21st, a daily statewide news talk show on WILL/Illinois Public Media. She graduated summa cum laude from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign with a B.S. in journalism and founded an art magazine called The Collective.

Connect via Twitter and LinkedIn or email her at cav2149@colmbia.edu.